COP21 Paris: Where’s the money?

Finding solutions to climate change will not only depend on political negotiations at the COP21 summit in Paris, but the money to support technologies aimed at keeping global temperatures in check.

Raising funds for climate projects has increasingly taken centre stage in United Nations-driven climate talks, with diplomats clambering to come up with the annual goal of $100 billion before the Conference of Parties, or COP21, begins in Paris on November 30.

They are only halfway there. According to estimates by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), pledges averaged $57 billion (OECD breakdown) for the past two years.

Developing countries argue that without the money, they are unable to invest in new, cleaner forms of energy and transport, or prepare for potentially devastating effects of rising temperatures.

Pledges and temperature rises

A report published in October by the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), an independent scientific group of European climate experts, predicts that even if all pledges are applied, the global temperatures will nonetheless rise by 2.7°C. For the group, this still represents an improvement compared to its assessment of pledges at last year’s climate summit in Lima, which predicted a 3.1°C rise.

And according to the climate data website Carbon Brief, national climate pledges, also known in UN jargon as INDCs (intended nationally determined contributions), submitted up to now, show that poorer countries will need trillions of dollars in support to achieve this over the next 15 years.

“Intelligent spending”

Getting firm national pledges to the Green Climate Fund – to serve as the centerpiece of climate finance – has however been a complex process.

Stefan Marco Schwager, an advisor to the Swiss environment ministry on international climate and biodiversity finance, told swissinfo.ch that in his view, the Green Climate Fund was not evolving “as fast as many of us would have liked”.

Since last year, United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon has focused much effort into converting the initial pledge of $10.4 billion to the fund into formalised agreements.

Switzerland has promised $100 million to the fund, to be paid in three installments, between 2015 and 2018.

Schwager said now that “there is money in the piggy bank” the focus is on how it will be spent “not only fast but intelligently and with impact”.

The Swiss expert explained that greater clarity on what constitutes climate finance is still needed – an issue debated at length last year at the Lima conference.

For donors in developed countries, corruption in the disbursement of funds has also solicited “some concern”, according to Schwager. “Whenever there is money flowing there is the risk of corruption, abuse, inefficiency”.

Private sector

The lion’s share of funds that will be invested to counter climate change is however expected to come from the private sector.

At last year’s COP, Christiana Figueres, executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC, expected some $90 billion would go to clean technology and infrastructure over the next 15 years, most of it coming from private sector investments.

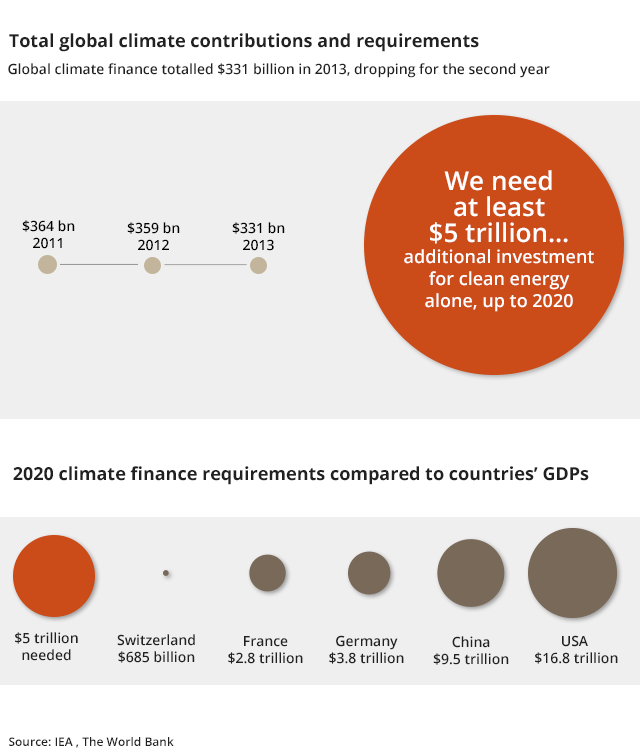

The International Energy Agency, too, says that approximately $5 trillion will have to be spent on clean energy by 2020 to keep temperature rises within limits.

While such figures may seem colossal, some business leaders appear unfazed.

Daniel Rüfenacht, vice-president of corporate responsibility at inspection and verification firm SGS, believes corporations are already doing their part. But he says governments need to work with the private sector. “The schemes that states will put in place will depend on technology and innovation which will come from the corporates.”

Bertrand Gacon, president of Sustainable Finance Geneva – an association of individuals sponsored by private companies, including many banks, and the cantonal government – held that the numbers being articulated for climate finance should be put into context. “What humanity is spending on cigarette sales is more than what humanity should be spending to solve climate change.

“The figures are not out of reach. The private sector is already providing between two thirds and three quarters of the funds needed to fight climate change. Financial markets are already doing part of the work,” he stated.

Green bonds

Since last year, the green bond market, funding projects that have positive environmental or climate benefits, has grown rapidly to reach over $40 billion in new issuances. The bonds, which are fixed income, essentially finance projects that range from renewable energy plants, improved energy efficiency and green transportation technology.

Gacon said that while green bonds still represented “a drop in the ocean” compared to the overall size of financial markets, it was “starting to represent a significant amount of money” for climate change.

He explained that their issuance meant that “for the first time we have a mainstream impact product… that private and public sectors – governments, pension funds – can invest in”. After their initial launch which was supported by the World Bank, green bonds have evolved in sophistication, allowing investors to focus more on where the money is going, rather than just who the issuer is.

The bank, Credit Suisse, and Zurich Insurance have both played active roles in boosting the green bond market. Last year, Zurich agreed to invest $2 billion in green bonds, though recently attracted attention when its head of responsible investment said it would not rule out buying green bonds from fossil-fuel producers, again sparking concern over what may define green investments within the market.

Impact investing

A Geneva-based investment management company, Quadia, is one of a growing number of companies in Switzerland focusing on another area of green finance: impact investing. This offers finance to innovative businesses that may otherwise have difficulty finding funds.

More

The hive effect

The business case, Gacon said, was very attractive for investors not only because they are having a social and environmental impact, but also due to the financial performance with high returns and diversification in their portfolios, because very often they are investing in countries and projects that are not covered by the mainstream finance and investment community.

Gacon, who is also head of impact investing at the private bank, Lombard Odier, says bankers still needed to adapt to a “cultural change”, and become more aware of all the benefits of sustainable finance.

Carbon footprint

He says externalities, which include the environmental and social costs of carbon use, could also be factored into investments, as well as the development of simple ways to measure one’s carbon footprint to help change investors’ behaviour.

“These need to be reinforced if we want to achieve all the targets”.

SGS’s Rüfenacht added that many publicly-traded businesses realise that their reputations rely increasingly on doing “the right thing”, and assuring that operations and investments respond to the public’s concerns on climate and human rights.

But Schwager warned that “no one just wants green labelling. It’s like washing detergents, where they have the same ingredients but you just put a new sticker on”.

The environment ministry’s climate finance specialist says he, too, has seen positive moves in the private sector, impelled by a growing awareness of climate change amongst consumers, who wanted to know that changes are “fast enough and big enough”.

“Very often discussions and negotiations stop at the bean counting and you produce a nice report with pictures” of projects that have been supported.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.