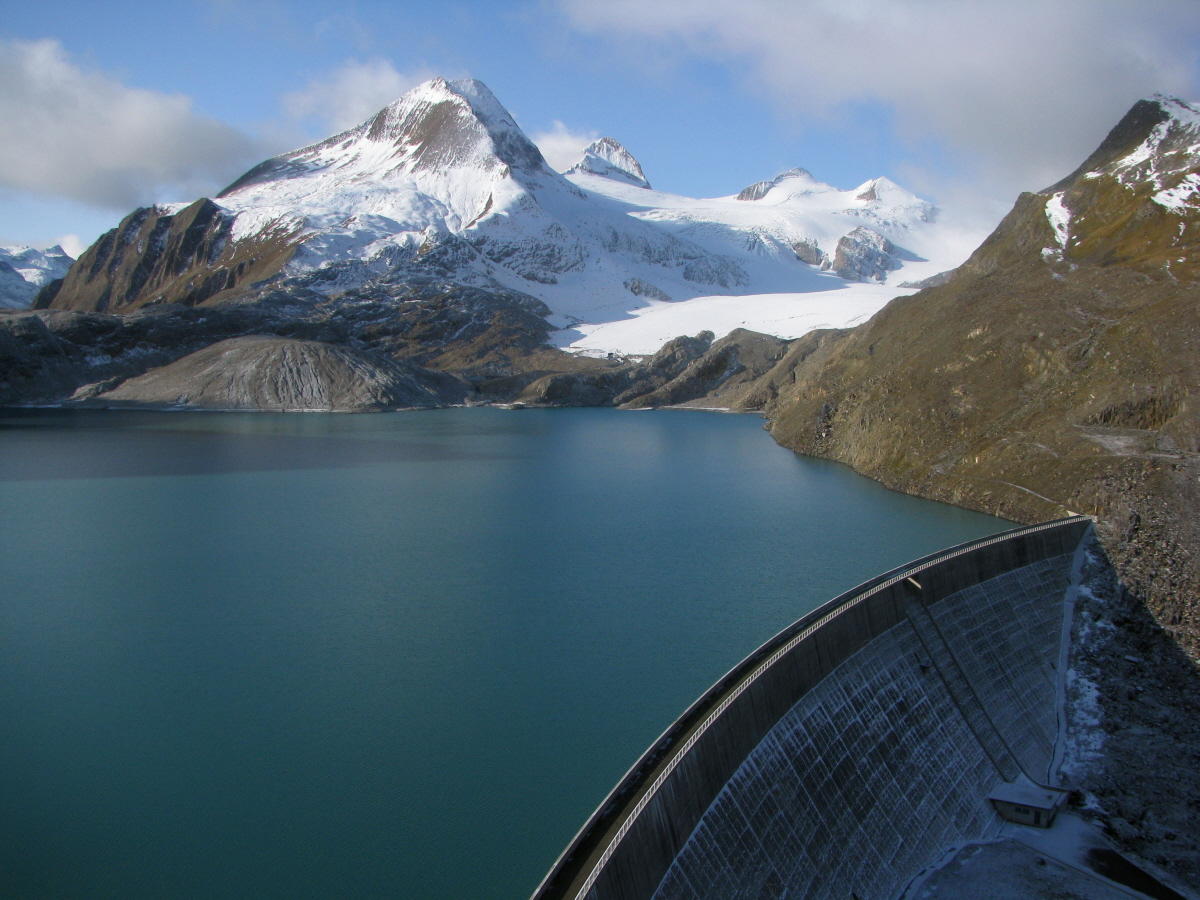

Dams could potentially replace melting glaciers

Alpine glaciers are an important source of water for Europeans but they are melting away due to global warming. Swiss-led researchers say that water management in reservoirs and dams could help counter future water shortages.

In the study published in latest Environmental Research LettersExternal link, the team simulated the effect of climatic change on glaciers across the European Alps. They estimated that two-thirds of the effect on seasonal water availably could be avoided if water was stored in areas that are becoming ice free.

This is the first time such as estimate has been made, the Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, one of the study leaders, said in a statement on FridayExternal link.

Higher temperatures are expected to lead to substantial glacier retreat and snow-covered areas being reduced in size and duration. This in turn could affect the seasonality of water runoff and result smaller water yields from high-mountain areas.

Scientists looked whether this could be mitigated by managing water through reservoirs.

“The basic idea is to transfer the additional water expected to be available during spring because of an earlier onset of the melting season, to the summer months. This could compensate for the reduction in water yields expected as a result of glacier shrinkage,” the statement said.

The two-thirds figure was generated using the latest climate projections and a numerical glacier model developed recently. Scientists estimated that a temporary storage of about 1 km3 of water – the equivalent of a water cube with edges 1 km long – would be required.

Artificial dams

The authors then “somewhat provocatively” compared the storage needed with the potential volume that would be available if artificial dams were installed near retreating glaciers.

“That was a bit from the environmental point of view, putting forward the idea of putting a dam in front of every glacier is like some sort of heavy engineering, so this is the provocation,” explained Daniel Farinotti, from the WSL’s Mountain Hydrology and Mass Movements unit.

The scientists simulated the presence of dams at current glacier positions and computed the volume of each lake being formed. The results showed that the potentially available volume was ten times larger than the required one and that about a dozen centralised dams would be sufficient to meet the storage demand.

But this would only solve part of the problem, the authors say: it would be difficult to centralise the water of the about 4,000 glaciers across the Alps.

Plus you are effectively only shuffling water around in the year, Farinotti pointed out.

“What actually also happens is that you have overall less water during the course of the year. There’s no way you are going to generate more water by putting it temporarily in a dam site. So the overall water loss is not a problem that you are going solve with that strategy.”

Farinotti said it is possible that most of the glaciers in the European Alps could be gone in a 100 years.

In a sobering final statistic, the authors estimated that by 2100, the runoff from glaciers in the European Alps would drop by the equivalent of about 80% of Switzerland’s consumption today.

The study

Farinotti et al.: From dwindling ice to headwater lakes: Could dams replace glaciers in the European Alps? Published May 20 in Environmental Research Letters.

The WSL led study along with the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission in Ispra, Italy, and the Laboratory of Hydraulics, Hydrology and Glaciology (VAW) at the Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich).

A study released by the World Glacier Monitoring Service at the University of Zurich last year found that globally, glaciers are melting at a faster rate than ever before.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.