Have lessons been learned from science on climate effects?

For years scientists warned of a multitude of existential risks from unbridled climate change. It took a pandemic for many global leaders to realise that such threats were real, and that crisis response systems were unprepared. But will anything change?

One of the goals of the Geneva-based Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is to publish reports linking accelerating global warming to human activity. Thousands of scientists are regularly consulted and the reports serve as a key reference for policy, including international climate summits.

In 2014, the IPCC introduced a section on health and climate change in that year’s assessment report, a vast study that gauged a wide range of scientific information. It pointed at infectious diseases such as malaria and dengue spreading from mosquitos due to warmer temperatures. Earlier IPCC studies also mentioned air pollution from the burning of fossil fuels. Those warnings came in addition to droughts, tsunamis, hurricanes and other extreme weather events that threaten food supplies and access to water.

Maria Neira, director of public health, environment and social determinants at the World Health Organization (WHO) said that the link between the environment and disease is now clear. “The fact that we have strong deforestation, aggressive agricultural practices in some places involving pesticides and fertilisers, and we have the consumption and commercialization of wild animals, and aggressive urbanization, all of those factors contribute to the spillover of viruses.”

Warnings from science

Ebola, SARS and HIV are known to have also originated in animals, specifically in regions where humans invade animal habitats through environmentally destructive practices. An initial report by an international team of experts from the WHO and China which travelled to Wuhan suggested that the most likely source of Covid-19 was animal.

Many other scientists have warned over the years that changes in land use disrupt the balance in nature and provoke diseases to spill over from animal hosts to humans. Their voices were met mostly with indifference from policy makers.

That is expected to change. Since the start of the pandemic, Covid-19 has shed light on the link between environment and climate change for policy makers, through the impacts on health of environmental degradation.

“The IPCC kind of photographs a situation every few years, when something takes place that is so disruptive that it changes the way that we think about an issue. We will see much more of this later on,” said Dario Piselli, a consultant and researcher at the Centre for International Environmental Studies in Geneva, indicating the profusion of scientific reports and policy documents which have now linked the pandemic and health and the environment and climate.

The international science panel is expected to finalise its Sixth Assessment Report in the first quarter of 2022. An IPCC spokesperson told SWI swissinfo.ch it will “assess the literature on Covid-19 that has been published by the literature cut-off dates,” by the end of July 2021.

Over the past months numerous reports stemming from the pandemic have been published including a reportExternal link by UN Environment entitled “Making Peace with Nature” in February. It offered a synthesis of various global assessments in an effort to tackle interlinked environment and health crises.

Meanwhile, rExternal linkesearchers in Brazil warned that deforestation from agriculture and mining in the Amazon, and rising temperatures and rainfall changes, now heighten the risk of the emergence of new viruses, as species are put under stress.

Pandemic boost to climate action?

While such reports may have generated more public awareness and pressure on leaders to step up action, climate talks meanwhile have been on standby since the United Nations COP25 climate change summit in Madrid in December 2019.

For Piselli, the focus on health during the pandemic may help nudge climate talks forward. “Because it is such a tangible form of harm and very present in our legal system, it is one of the “allies” that could help us fight this battle (against climate change) and hold government to account for their commitments.”

First pushed back shortly after delegates met in Madrid, Covid-19 subsequently led to the postponement of the COP25 follow-up session in Glasgow. After the conference in the Spanish capital closed in disappointment with member states unable to agree on rules for a global carbon trading system and processes to channel new finance to countries impacted by climate change, some worried about lost momentum and delayed action.

Franz Perrez, Switzerland’s ambassador to UN climate negotiations told SWI swissinfo.ch that the lack of formal or even informal negotiations since Madrid is a “setback” and that delays due to the postponement of in person talks will make it more difficult to achieve ambitious outcomes in Glasgow. The COP26 is scheduled for November.

Nonetheless, there has been some momentum at the national level. Many developed countries have increased carbon emissions commitments since the start of the pandemic. The European Commission said the region’s stimulus package would put climate action at the centre of the European Union’s recovery, while an ambitious climate EU law aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. In Switzerland, a revised CO2 law will be voted upon in a referendum in June, that would allow the country to raise ambitions and recognise emissions caused by imports abroad.

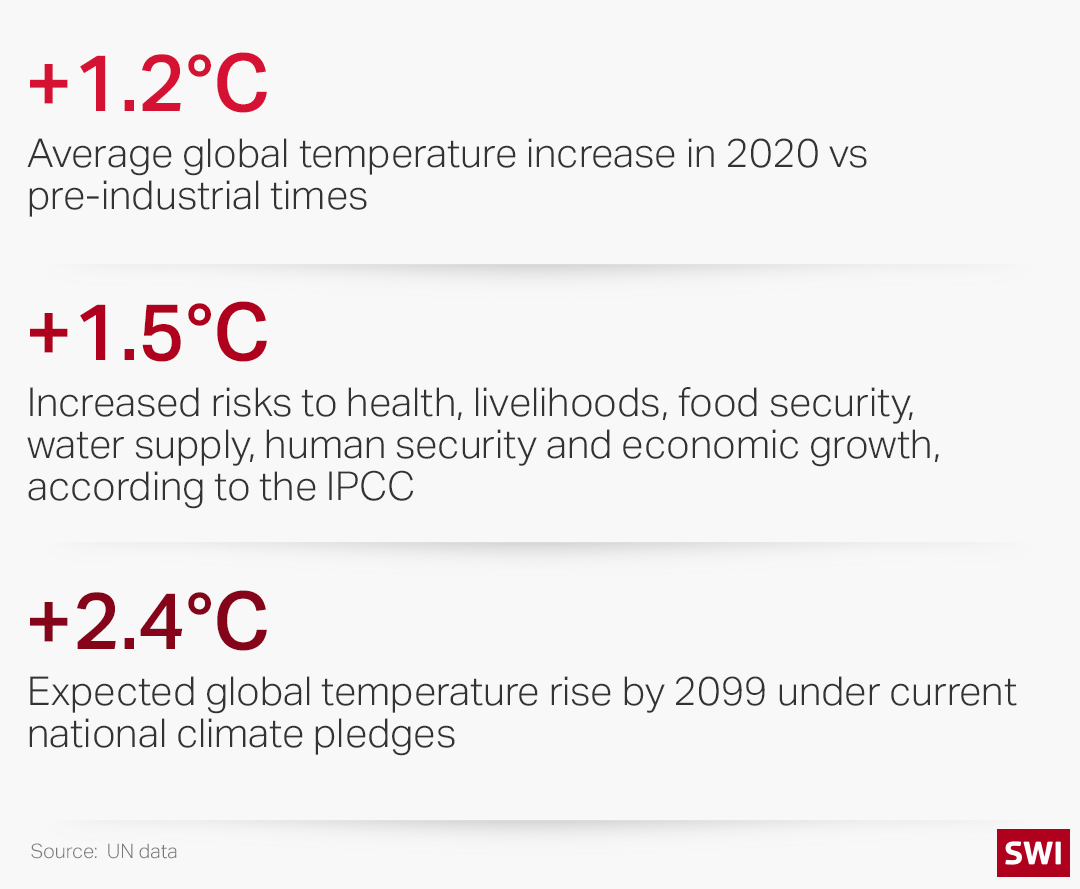

But overall, according to studiesExternal link, global pledges will still be not enough. Current commitments would allow the Earth’s average temperature to rise by 2.4 degrees Celsius by 2100 as compared to pre-Industrial levels. That is much above the 1.5-degree Celsius increase that the IPCC warns would provoke risks to “health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security and economic growth.”

With developed countries already lagging in a 2009 pledge to provide $100 billion (CHF90.1 billion) annually in climate finance to poorer countries before the pandemic, finance risks being an issue as countries commit huge sums of money into economic recovery plans and health.

“In this context, the pandemic affected the goal and the long-term outlook. It may provide an excuse not to scale ambition but also has put lots of pressure on low- and middle-income countries that are in debt distress or risk of debt distress as they had to front-load resources for the pandemic,” Piselli added.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has called for a scaling up of international public finance for climate as expected from the Paris Agreement.

Ambassador Perrez said it was important to learn about how finance could be more effectively delivered and deployed. “We need to look at challenges both on the recipient and donor sides and learn about what we can do better and increase overall amounts, impact and tools, and to look at all financial flows, including private flows, and that there is a strong commitment towards that.”

Role of another treaty

A year after the WHO’s last health assembly issued prescriptionsExternal link for a “healthy and green recovery”, Neira, said positive signals need to be conveyed to people amid the pandemic for action to take place.

“Society is not ready to hear about alerts and the next crisis, which is already here,” she said. “If instead we speak in positive terms and say that while the crisis is here, if we stop polluting and create a clean energy transition and design cities in a more livable way, we can have enormous benefits for health and the economy and society as a whole.”

Recently the WHO has forwarded the idea of a pandemic treatyExternal link “to build a more robust global health architecture”.

Though details of the treaty are not yet known, Neira said environmental risks must be considered. “Any way forward needs to look at environmental health and environmental risk factors,” which together with animal health, is part of an interconnected “one health” approach.

After efforts to drum up enough financial support from wealthy counties for the Covax initiative by the WHO and partners to help poorer countries receive vaccines, many of the same countries, on the frontlines of climate change, worry about nailing the urgency to act quickly and effectively.

But for the WHO expert, assuring a basic public health agenda could carry many of global challenges a long way. She said many of those recommendations are already present in the global climate agreement signed in 2016 in the French capital, including emissions reductions and incentives to reduce deforestation.

“The message is if you are tackling climate change, what you are doing is public health. If implemented, the Paris Agreement will have fantastic health benefits, and will be a win-win on so many fronts.”

More

Coronavirus: the situation in Switzerland

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!