In pursuit of the crystal hunters

In the Swiss Alps, archaeologists are exploring a unique mine used as far back as 8000 BC. Fragments of mountain crystal provide clues to how hunter-gatherers worked at the region’s only known prehistoric rock crystal mining site. Our reporter has been following their work over the course of the three-year project, which runs through December 2022.

Our crampons crunch into what’s left of the Brunnifirn glacier in central Switzerland, and when we pause, we can hear the trickle of melting ice beneath our feet. The late-summer landscape is an otherworldly basin of grooved old snow ringed by bare, jagged peaks.

During the Stone Age, hunter-gatherers trekked all over the Alps to find crystals. That might sound New Age, but there was nothing spiritual or mystic about their mission. These prehistoric craftspeople were searching for glittery treasures to turn into arrowheads, blades, awls and other tools.

Independent archaeologist Marcel Cornelissen – a jolly 45-year-old with a passion for mountain sports – has been pursuing these miners for years, squeezing his annual fieldwork into brief windows dictated by season, snow cover and weather. This expedition in September 2020 only materialized thanks to a receding glacier and a tip-off from a modern-day crystal hunter, who found a heap of crystal shards, two pieces of antler and some bits of wood while he was out looking for minerals.

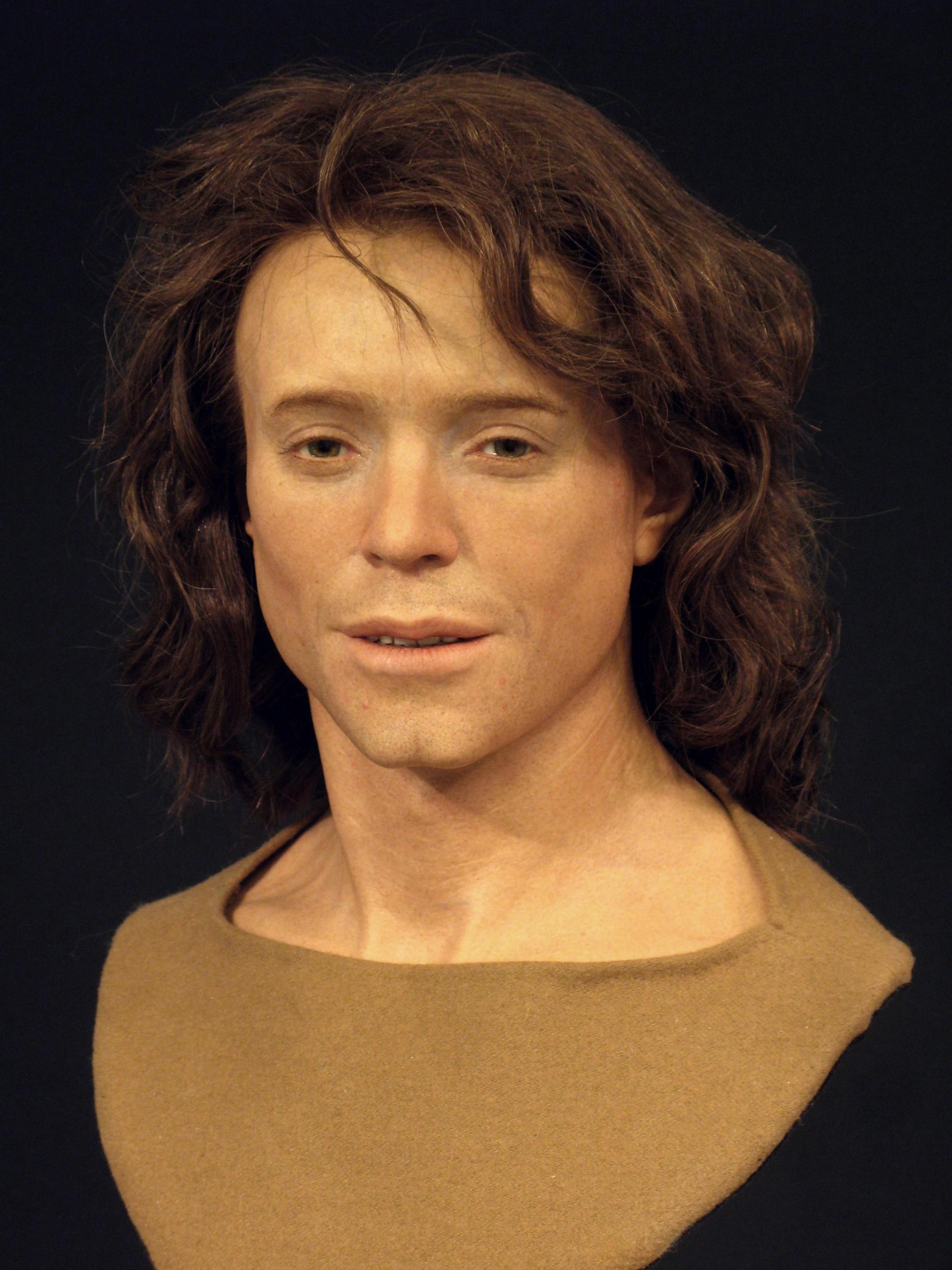

Wood and antlers at 2,831m – an elevation inhospitable for most vegetation and animals? Archaeologists like Cornelissen depend on leads from the public, especially in remote areas. One piece of antler disintegrated upon thawing, but specialists were able to radiocarbon date the other piece to 6000 BC. That makes it the oldest find of its kind preserved in Alpine ice – and considerably older than Ötzi, the mummy of a man who died in the northern Italian Alps around 3200 BC and was found in 1991.

Marks on the antler suggest that it may have been used to extract the quartz crystal. According to the ‘Cultures of the Alps’ Institute – which commissioned the research project Cornelissen is leadingExternal link – this is the only known prehistoric rock crystal mining site in the Gotthard region. Additional sites have been found about 100km southwest, in Simplon and the Binntal valley in canton Valais.

The dig

On this September morning Cornelissen himself is the miner, leading the excavation on behalf of canton Uri’s Department of Monument Preservation and Archaeology. It’s his third time at the Brunnifirn glacier looking for artefacts, and he’s hoping there’s more to discover before the project wraps up at the end of December 2022. His finds suggest that people mined the site as far back as 8000 BC.

“It would be nice to find a few more pieces to really make sure,” he tells me. “I also hope that we have enough material in the end that we get a better impression of how the people worked.”

Meanwhile, his three colleagues are excavating a small patch atop a rocky little hill overlooking the glacier. Bare of snow, it measures about six square metres. Space is tight so I keep out of the way, perched on a large stone studded with small smokey quartz crystals on its underside – so sharp they bloody my fingers, but so fine that I don’t feel any pain.

The initial excavation work, however, is anything but delicate. To clear space, Annina Krüttli and the other archaeologists shove stones and boulders down the hill. Their spades and trowels dig noisily, clinking into the rocks.

Krüttli takes a break to explain their strategy for uncovering archaeological treasure. “What we want to do is get down to what you could just call the earth, because right now we’re just sorting through lots of rocks,” she says. “There might be finds on the surface that are really interesting, so we will just remove the top five centimeters and put it all in bags and take it down when we leave.”

By the time they’re done, they’ll need a helicopter to haul over 60 bags down to the village of Sedrun, where cars await to carry them onward. The robust plastic sacks are in fact garbage bags, which initially seem too ordinary for potentially precious artefacts. But as Cornelissen points out, they are ideal: “This is what people left behind. It’s what they didn’t want, and that’s what we’re taking.”

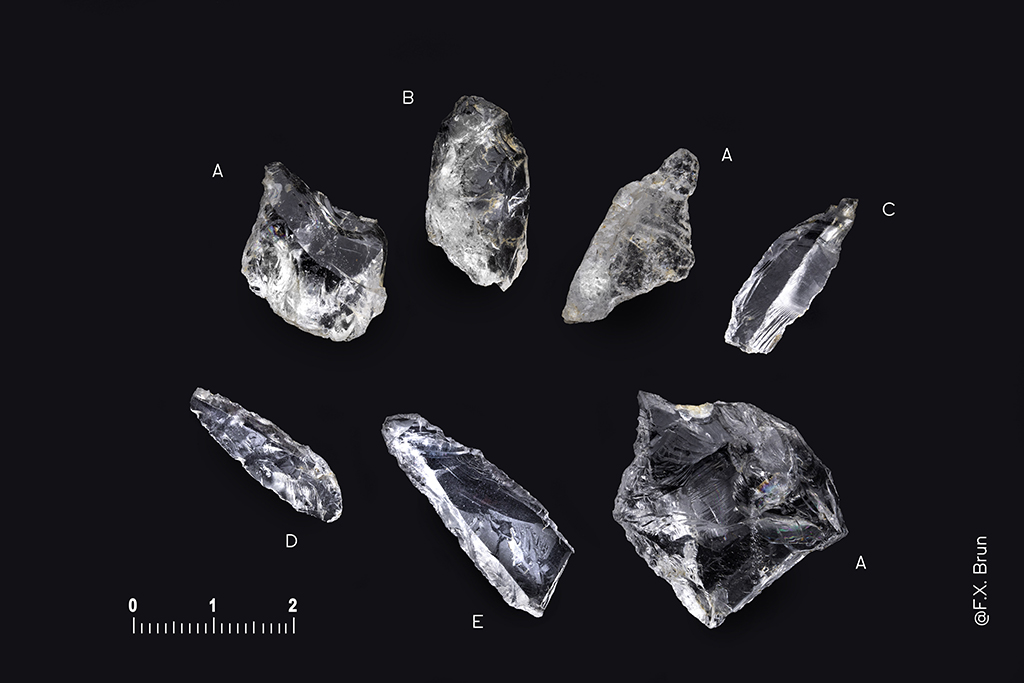

These items may have been “trash” to these primitive engineers, but they have a certain beauty. Cornelissen shows me a fragment of crystal that’s just been uncovered: vaguely triangular – and to his expert eye – clearly formed by a human.

“It’s not a tool or anything. It’s rubbish – the leftovers of the production process,” he says. Its form matches similar finds from other Swiss sites dating back 8,000 years ago, and that may well be the last time that somebody held it.

“There were no farms, no churches, no permanent buildings, but they were here and they extracted the rock crystal.” It’s a lot to take in when you compare their leavings to modern-day litter like candy wrappers and plastic bottles.

He seals the crystal fragment in a transparent baggie, with a slip of paper noting the exact location of its discovery. He’ll do this for the best finds that surface over the next two days; the remaining artefacts and soil will end up in the black garbage bags, also carefully labelled.

Time and space

The sun gets low and the temperature drops – time for us to pack up. We strap on our ice-gripping crampons and rope ourselves together. Meltwater burbles under our feet; it’s a playful sound, but also a reminder of how the landscape is changing. Between 1973 and 2010, the Brunnifirn glacier lost nearly a quarter of its mass, shrinking from 3.02km2 to 2.31km2External link. On the other side of the glacier, dinner and bunk beds await us at the Cavardiras hut at 2,649 metres.

Did the crystal hunters sleep up here too? Cornelissen thinks so because of the tools he’s found nearby – simple ones that they likely made on site for use over a couple of days.

“They weren’t just here for an hour or so to grab a few crystals to take away. No, they probably made a camp, maybe spent the night and fixed some equipment or some trousers, and maybe had a quick snack and the next day moved on,” he says.

Understanding the seasonal cycle of extracting crystals could shed light on how humans moved across the landscape at the time: A trip up the mountain may have been part of a cross-country hunting expedition; the quartz crystal may have had a certain societal cachet, much as it does among today’s mineral collectors. Nobody can know for sure. In any case the area has no flint, a typical stone used for prehistoric tools.

The next morning, I need to go home, as does archaeologist Christian Auf der Maur – much as he’d like to keep digging. Tall and sure-footed, he offers to hike with me on the challenging alpine route which starts off snowy, stony and steep before we reach the summit and head down into greenery dotted with Alpine flowers and blueberries. It takes hours – ample time to chat about the dig.

How do he and his colleagues cope with the research limits imposed by time and space? After all, there might still be incredible artefacts waiting to be unearthed just a few trowel strokes away.

“That’s the life of archaeologists. When you do excavations, nearly every time there’s something you need to leave back. You have to live with that and try to get the most out of the data and findings to bring down to the lab,” says Auf der Maur, who works for canton Uri’s archaeology departmentExternal link. The team hopes to have found the most important ones on this field trip. Before this particular project winds down at the end of the year, they will have had a couple more chances to inspect other sites in the area.

The washing and sorting

Two months later, Cornelissen greets me outside of a warehouse in eastern Switzerland. He’s traded his mountain gear for rubber gloves and a waterproof apron so that he and Krüttli can sieve through the 976 kilos of soil, rock and crystal they gathered up at the Brunnifirn. Now it’s time for the loot to get a shower.

As the water gushes and clumps of soil wash away, the stones start sparkling – as do Cornelissen’s eyes when promising shapes begin to emerge. Now comes the painstaking task of sorting each piece by hand. This means hours of squatting over a tarp and picking through the wet minerals, placing the potentially “good” ones in trays and chucking away buckets full of rejects.

Krüttli then takes the potentially valuable pieces into the warehouse and slots them into drying racks – all the while keeping track of what was found where. The meticulous documentation carried out up at the dig site is paying off. If the findings merit it, these notes will make it possible to revisit precise locations to gather more clues. Even if there are no incredible individual finds in this round, the archaeological value of the collection is huge.

“If we imagine having 50,000 of these little shards, all of them analyzed, you have the power of numbers behind you,” says Krüttli while checking whether any trays are dry enough to seal into storage bins. “That’s how you can actually say things about individual bits that might look a little insignificant.” Enough data will enable them to put their finds into a bigger context, whether it’s cultural, historical or environmental. Each shard is a puzzle piece linking the past to the present.

With traffic barreling past the wind-swept asphalt, it’s this firm belief that sustains the researchers through the hours of strenuous manual labour needed before they can get a more precise handle on the finds. When they finish – three days later – the next stop for the circa 300 kilos of retained artefacts will be Cornelissen’s personal basement in a suburb of Bern.

The inspection

In August 2021, Cornelissen invites me to his home, where he has also stored artefacts from previous research projects. Outside his front door, a pair of wooden clogs nod to his Dutch roots. Inside, sturdy plastic boxes brim with potential links to our common ancestors who roamed the Alps between 9500 and 5500 B.C. Cornelissen pours a few handfuls of quartz, crystal and granite onto his kitchen table. Equipped with tweezers, good light, magnifying loupe and measuring gauge, the researcher is reviewing his haul.

“That’s a good one – that goes into the artefact pile. And this one? Probably in the ‘maybe’ pile,” he says as he flicks through the pieces.”

Like a jeweler appraising a gem, he squints at a quartz fragment the size of a tooth. Turning it in the light and murmuring thoughtfully, he suspects it was part of a blade or perhaps a drill-like tool. He measures and labels the find before sealing it in a palm-sized plastic bag and entering the data into his laptop. Now it’s one of hundreds recorded in his spreadsheet, the columns full of notations on the material, shape, condition and other characteristics of each piece. As for the find itself, Cornelissen will file it in a sealed plastic box typically used to store fishing lures.

He’s placed some of his best specimens on a sheet of black paper, which sets off the contours formed by skilled hands so many thousands of years ago. As I try to grasp their significance, I remember something Krüttli told me while they were washing the rocks outside the warehouse.

“Those original crystals must have been huge for the hunter-gatherers to be able to make enough tools. It takes a lot, lot longer for crystals to grow than the period that has passed between them being there and us arriving,” she said. “So I have this picture of them sitting behind a rock laughing at us because we were just a little bit too late.”

From millennia to mere months and years: The archaeologists’ work in pursuit of these prehistoric crystal hunters may never be truly finished. But through their detailed spreadsheets and carefully labelled artefacts, they’re paving the way for future investigations of this slice of human history.

What to do if you find something unusual

When glaciers and ice patches melt, archaeological finds thaw out. They date to all periods, from the stone ages to the 20th century. These objects allow us fascinating insights into the past. Those made of organic materials such as leather, fur, textiles, antlers or wood rarely survive, but they do in ice and permafrost. After defrosting, however, they quickly decompose.

If you find something in or near Swiss ice: You can take photos and submit them to the local authoritiesExternal link, who may send an archaeological team to rescue the material. Draw the location of the find on a map or note the site’s coordinates and mark the site. Collect finds only under immediate threat of destruction or if the location cannot be found again.

More

Edited by Nerys Avery and Sabrina Weiss

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.