Lab-developed chocolate passes the taste test

The chocolate of the future may come out of a bioreactor. A research team in Switzerland has just developed lab-grown chocolate for the first time.

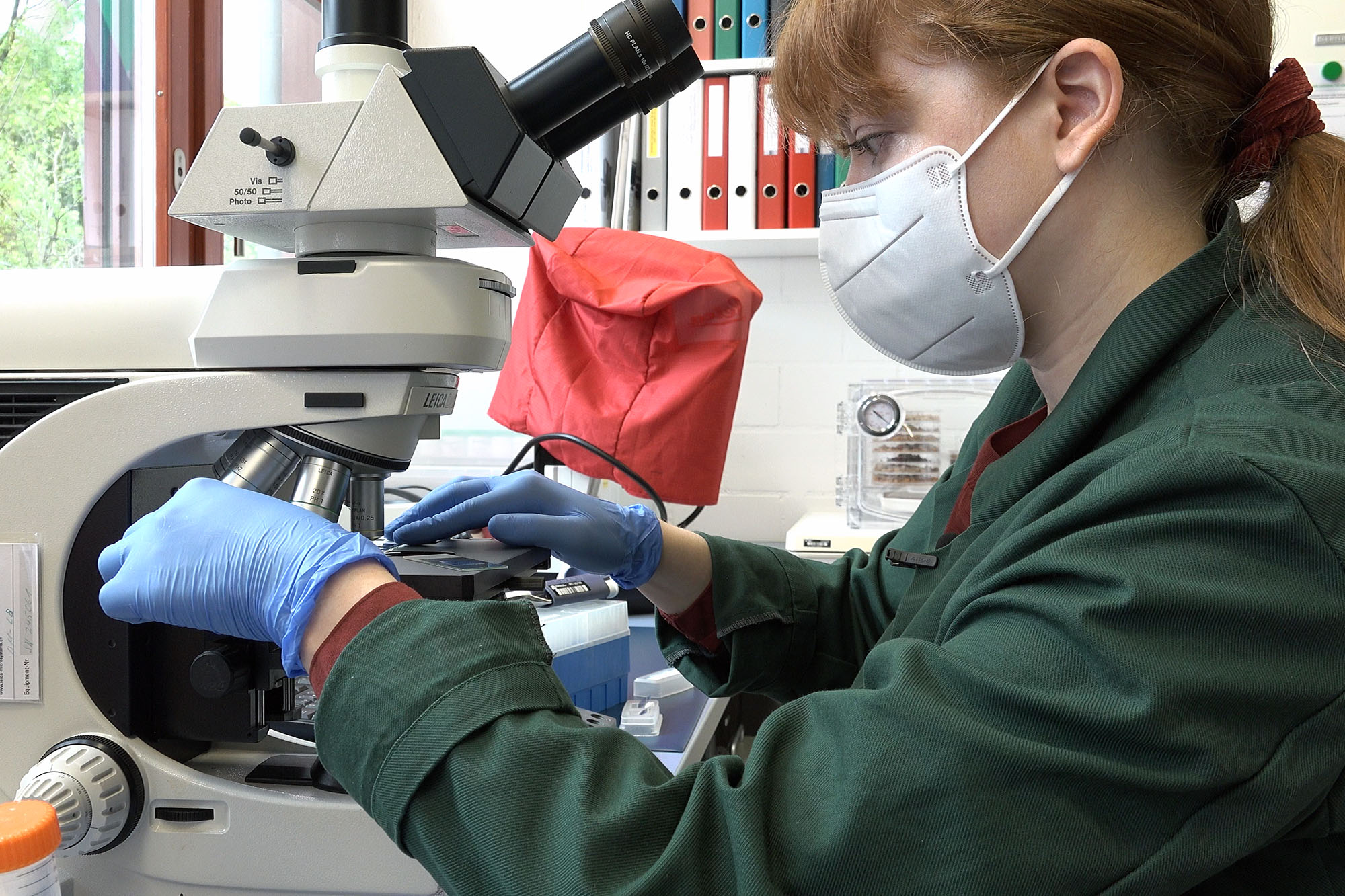

The laboratory at Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) is full of various scientific instruments. In the lab, a brown mass is being shaken around inside a big, bulging plastic bag, while a constant hum is heard in the background. Next to it is a glass container in which more brown matter is being stirred around.

“Here in the lab we are actually just imitating processes that happen in nature,” says Regine Eibl, who teaches at the ZHAW, External linkan institute of technology in Wädenswil. Prof. Eibl heads the Cell Culture Technology department and is part of the research team that has just developed lab-grown chocolate.

Chocolate out of a tank

The “chocolate” was the result of biotechnologists and food technologists from the Wädenswil institution getting together.

At first, Eibl’s team, which spends most of its time growing cell cultures for the pharmaceutical industry, never intended to create a cell culture to make chocolate

“The idea came from a colleague of mine, Tilo Hühn,” she recalls. “He asked me if we could try to extract plant-based cell cultures from cocoa beans. We wanted to see if these cell cultures would produce polyphenols, which happen to be very important for the perception and sensory effects of chocolate.”

A study that appeared in 2020 in Applied Sciences sums up the results of 26 opinionExternal link surveys carried out in different countries regarding in-vitro cultured meat. For the first time, lab-grown meat was approved for sale by an official regulator – this happened in SingaporeExternal link.

The findings of this meta-study indicate that in many countries there is a considerable potential market for cultured meat products. Cultured meat is viewed generally as more acceptable than other food technologies such as genetically modified organisms, and more attractive than other alternative sources of protein such as insects. It is not, however, found as attractive as products made of plant-based proteins. But there is some evidence that it would appeal to meat-eaters who do not like other synthetic products.

Foodstuffs out of a tank

Hühn is already well-known in the chocolate world. Several of his projects have made headlines, including a chocolate product elaborated with the entrepreneur and pop singer Dieter MeierExternal link (singer of Yello), which will go into mass production in the coming weeks. The product has a stronger chocolate aroma than in traditional chocolate due to the extration of water from the cocoa beansExternal link

But “growing” chocolate in a laboratory has to be Hühn’s most ambitious project so far. After cleaning the surface of the cocoa fruit, the cocoa beans are first extracted in a sterile process, then quartered using a scalpel and incubated on a culture medium at 29°C in complete darkness.

A kind of rough scab known as callus grows on the cut surfaces after about three weeks. This can be reproduced at will. “It is done in a very simple culture medium”, says Eibl.

Next, this material is put into shaking flasks, into which what is known as a suspension culture is added, and it is multiplied in a bio-reactor. “Reactor is a terrible word. it’s really just a tank, like the kind you ferment wine in”, says Hühn, who himself comes from a wine-making family.

Finally, the cell culture lets you make as much chocolate as you like. You could think of it as something like a kefir fungus or sourdough starter, which you can take a bit from when you need it. The food industry is now very interested in these cell cultures, notes Eibl.

“We want to see what the future of foodstuffs out of a tank might look like. Mind you, a complete de-territorialisation, getting away from the earth completely, is not what we’re after,” explains Hühn. The main idea, he says, is “creating conditions that don’t take up so much of the environment and leave a very light footprint when we make these products”.

Worldwide demand for chocolate has been on the rise, since it gradually changed from being a luxury to a consumer item. This has consequences all along the supply chain: from procurement of raw materials, to production and subsequent price pressures. “There are also really unacceptable situations involving child labour in several of the producing regions. The way we are going here could lead to a number of problems being solved,” says Hühn.

Revolution in the supply chain?

This kind of production could have a major impact on easing supply chains worldwide. “Our primary goal is not to bypass agriculture and deprive farmers of their living,” says Hühn. It is to test alternatives. On this point, he cites the Nagoya ProtocolExternal link. It states that people from whose environment a given genetic resource is extracted should get a monetary transfer.

There are as yet no figures available on the energy footprint of their procedure, says Hühn. That analysis is ongoing in tandem with their current research project. But the upside and downside of the lab procedure are emerging.

On the up side, no transportation or use of pesticides. The composition of the medium in which the cells grow can also be carefully monitored. On the down side, the need to treat water used in the process.

Switzerland’s chocolate industry association, Chocosuisse, declined to comment on the topic.

On the aroma trail

In the mouth, lab-grown chocolate feels just like traditional chocolate – which we brought along for comparison. The big difference lies in its rather fruity taste, which is immediately apparent. Flavours in conventional chocolate take more time to unfold.

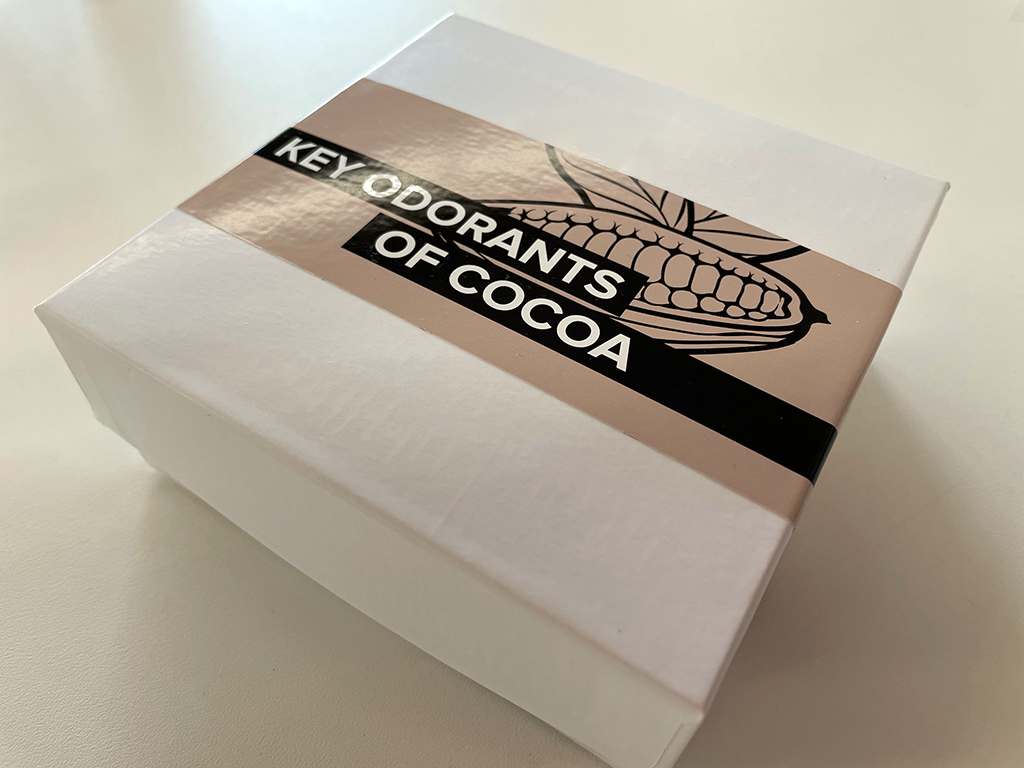

Researchers Irene Chetschik and Karin Chatelain are in charge of a project developed to detect the flavours present in the different kinds of chocolate.

Just in the past few weeks, they have decoded what might be called the scent DNA of chocolate or cocoaExternal link. They have now developed a kit with 25 different scents which occur in chocolate, such as flowery, fruity, spicy or earthy. The kits are similar to those used in oenology. Several dozen have already been sold.

“Chocolate has a very characteristic flavour, unique in its composition,” says Chetschik. “What is more, chocolate or cocoa is full of healthy substances such as polyphenols.”

The most interesting thing about cocoa aroma is that in all the ingredients present in chocolate there is no component that actually smells like cocoa, she adds. “The cocoa aroma is a combination of various chemical molecules with different-smelling qualities.”

Alternative for the future?

To date, lab-grown chocolate is still far more expensive than the tradtional kind. A hundred grammes of traditional organic chocolate costs CHF2.70 ($2.90) against an estimated cost of CHF15 to 20 for the Wädenswil product, according to Hühn.

Larger scale production will bring the price down, he adds.

Compared with processes for producing meat in a laboratory, this approach is “definitely cheaper, and has less impact on the environment”.

No mass production is currently planned. The next steps for the researchers will be to continue comparing the production process between lab-grown and traditional chocolate.

Huhn insists, however, that lab-grown food will not become an alternative to conventional agriculture.

“We will not be making traditional production of cocoa beans obsolete, nor would we want to.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.