How Swiss scientists are trying to spot deepfakes

As videos faked using artificial intelligence grow increasingly sophisticated, experts in Switzerland are re-evaluating the risks its malicious use poses to society – and finding innovative ways to stop the perpetrators.

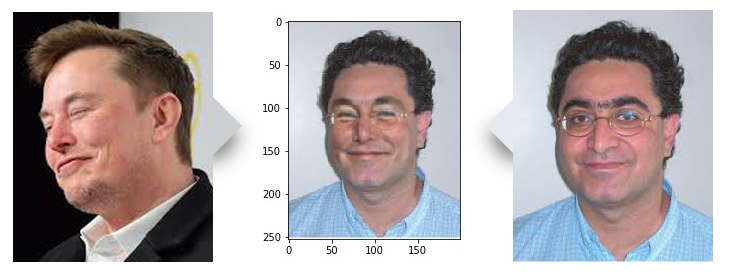

In a computer lab on the vast campus of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), a small team of engineers is contemplating the image of a smiling, bespectacled man boasting a rosy complexion and dark curls.

“Yes, that’s a good one,” says lead researcher Touradj Ebrahimi, who bears a passing resemblance to the man on the screen. The team has expertly manipulated Ebrahimi’s head shot with an online image of Tesla founder Elon Musk to create a deepfake – a digital image or video fabricated through artificial intelligence.

It’s one of many fake illustrations – some more realistic than others – that Ebrahimi’s teamExternal link has created as they develop software, together with cyber security firm Quantum IntegrityExternal link (QI), which can detect doctored images, including deepfakes.

Using machine learning, the same process behind the creation of deepfakes, the software is learning to tell the difference between the genuine and the forged: a “creator” feeds it fake images, which a “detector” then tries to find.

“With lots of training, machines can help to detect forgery the same way a human would,” explains Ebrahimi. “The more it’s used, the better it becomes.”

Forged photos and videos have existed since the advent of multimedia. But AI techniques have only recently allowed forgers to alter faces in a video or make it appear the person is saying something they never did. Over the last few years, deepfake technology has spread faster than most experts anticipated.

The fabrication of deepfake videos has become “exponentially quicker, easier and cheaper” thanks to the distribution of user-friendly software tools and paid-for services online, according to the International Risk Governance Center (IRGC)External link at EPFL.

“Precisely because it is moving so fast, we need to map where this could go – what sectors, groups and countries might be affected,” says its deputy director, Aengus Collins.

Although much of the problem with malign deepfakes involves their use in pornography, there is growing urgency to prepare for cases in which the same techniques are used to manipulate public opinion.

A fast-moving field

When Ebrahimi first began working with QI on detection software three years ago, deepfakes were not on the radar of most researchers. At the time, QI’s clients were concerned about doctored pictures of accidents used in fraudulent car and home insurance claims. By 2019, however, deepfakes had developed a level of sophistication that the project decided to dedicate much more time to the issue.

“I am surprised, as I didn’t think [the technology] would move so fast,” says Anthony Sahakian, QI chief executive.

Sahakian has seen firsthand just how far deepfake techniques have come to achieve realistic results, most recently the swapping of faces on a passport photo that manages to leave all the document seals intact.

It’s not only improvements in manipulation techniques that have experts like him concerned. The number of deepfake videos online nearly doubled within a single nine-month period to reach 14,678 by September 2019, according to an estimate by DeeptraceExternal link, a Dutch cyber security company.

Risk areas

Most targets of deepfakes created with the intent to harm are women whose faces have been transposed onto pornographic footage or images. This type of usage accounted for 96% of online deepfake videos in 2019, according to Deeptrace. Some appear on dedicated deepfake porn sites, while others are circulated as so-called “revenge porn” to sully the reputation of victims.

“Online harassment and bullying are recurring themes,” says Collins.

By contrast, there have been few known cases of deepfakes deployed to commit fraud. Most of these have taken the form of voice impersonation to trick victims into sending money to the perpetrator.

Still, businesses are taking note. Companies including Zurich Insurance, Swiss Re and BNP Paribas all sent representatives to a recent workshop at IRGC on deepfake risks. Sahakian at QI says that the potential use of deepfake videos in accident claims, for example, is a concern among insurers he works with.

“The tech now exists to make today’s KYC [Know Your Customer] obsolete,” he says, referring to the process of verifying the identity of clients and their intentions in order to weed out potential fraud.

More

How a Swiss programme is teaching online privacy to children

The rise of deepfakes has also led to speculation about its potential use to interfere in political processes.

Those fears were confirmed when a manipulated video showing U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi made her appear to slur her speech. The manipulation was low-tech, a so-called “shallowfake”, but as Ebrahimi puts it, “It’s a sign of what can be done and the intent that’s driving this kind of manipulated media.”

Adapting to a new digital reality

Still, risk expert Collins warns that the use of synthetic media in politics needs to be placed in context.

“It’s possible that deepfakes could play a role in disrupting elections, but I’d be wary of over-emphasising the deepfake risk, or you risk taking your eye off the big picture,” he cautions.

What deepfakes do signal, he says, is “the potential gap that’s emerging between how quickly the digital information ecosystem has evolved and society’s ability to adapt to it”.

As an example, Collins comes back to the use of deepfakes as a cyber-bullying tool.

“It raises questions about how responsive legal systems are to individual harm online,” he says. “How do you get rid of harmful digital content once it’s been created, and how do you find the original creator or enforce any laws against them, especially if they’re based in another jurisdiction?”

Deepfakes can also help disinformation campaigns, further eroding the nexus between truth and trust.

AI to create and to detect

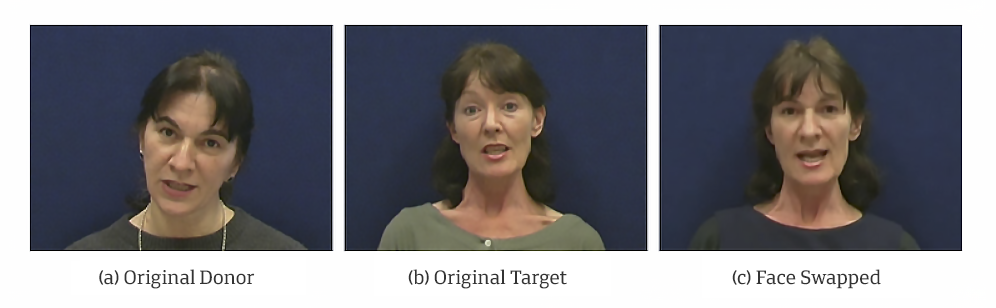

The technology may be causing panic in some quarters, yet not everyone agrees that deepfake videos are realistic enough to fool most users. Experts say that the quality of deepfakes today still depends largely on the creator’s skills. Swapping faces on a video inevitably leads to some imperfections in the image, explains biometric security expert Sébastien Marcel.

“The quality will be highly variable, depending on the manual intervention done to augment the image,” he says. If the creator makes the effort to finetune the result, the fake may be very difficult to detect, he points out.

Marcel and his colleagues at the Idiap Research InstituteExternal link in Martigny, in south-west Switzerland, are working on their own detection software, in a project grown out of efforts to detect the manipulation of faces and voices in video footage. Idiap is in it for the long-haul.

“This problem is not going to be solved today,” says Marcel. “It’s a growing research topic so we’re planning to put more resources into this area.”

To help it build on some initial results, the non-profit institute is taking part in a challenge launched by Facebook to produce deepfake detection software. The social media giant is pledging over $10 million to researchers worldwide (see infobox).

But just what difference detection will make is up for debate.

“It’s unlikely to provide a silver bullet,” says Collins. “Whatever the set of detection techniques, an adversary will find a way around it.”

A game of cat and mouse

Ebrahimi and Marcel both say that that their goal is not to come up with a fail-safe tool. Part of the detector’s job is to anticipate in which direction manipulators might go and tune their methods accordingly.

Marcel at Idiap foresees a future in which creators will be able to change not just one aspect of a video, like the face, but the entire image.

“The quality of deepfakes is going to improve, so we have to improve the detectors as well,” to the point that the cost-benefit ratio of making malicious deepfakes is no longer in the creator’s favour, he says.

EPFL’s Ebrahimi believes a major event, such as presidential elections in the United States, could give malign actors an incentive to accelerate their work, with a clear target in mind.

“It may be a matter of months or years” before the trained eye is no longer able to spot a fake, he says, and at that point, only machines will have the capacity to do it.

Twitter introduced a new rule in March 2020 against the sharing of synthetic or manipulated media content that can cause harm. Among actions it will take are labelling such tweets and showing warnings to users. YouTube, owned by Google, pledged that it will not tolerate deepfake videos related to the 2020 US elections and census that are designed to mislead the public. Facebook has launched a challenge, worth over $10 million, to support detection researchers worldwide. Both Facebook and Google have released datasets of deepfake images to help researchers develop detection techniques.

“The most widely circulated deepfakes tend to be parodic in character, involving high-profile individuals” like celebrities and politicians, says the International Risk Governance CenterExternal link (IRGC), making the point that “not all deepfakes are created with malicious intent.” Hollywood too has dabbled in deepfake technology, for example, to allow the return of long-deceased actors to the silver screen. EPFL’s Ebrahimi says that, if all goes according to plan, a by-product of the EPFL/QI project to develop deepfake detection software may be the eventual use of the same technology to create movie special effects.

Other potential positive uses of deepfake techniques include voice-synthesis for medical purposes and digital forensics in criminal investigations, according to the IRGC.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.