Reclaiming the supernatural

A University of Bern researcher has found a new way to interpret ghost stories – through a theological lens – that could deepen our understanding of the disparate fields of Victorian literature and astrophysics.

Ghost stories are a timeless and almost universally popular form of entertainment. They draw us in with a mixture of fear, intrigue, mystery and amusement. For postdoctoral researcher and lecturer Zoë Lehmann Imfeld, they offer still more.

Her research at the University of Bern’s English Department has sparked a paradigm shift in the literary world with its novel interpretation of Victorian ghost stories. In June, the Swiss National Science Foundation awarded her its prestigious Marie Heim-Vögtlin prize.

Lehmann Imfeld, who was born in London to a Swiss father and a British mother, moved 13 years ago to Switzerland, where she lives with her Swiss husband and two young children.

Lehmann Imfeld said she did not start by reading the ghost stories with a theological bent. Instead, she merely looked into general cultural preoccupations within the stories.

“The more I read, the more it became clear that concepts of the evil and the religious were being played off of each other quite closely,” she told swissinfo.ch.

She also had to overcome a popular conception that the Victorians were agnostics who stopped going to church, amid the modern calls for a rupture between church and state.

“[The ghost stories] were very much read in the sense that there was this void where religion used to be, and that there were these terrible scary things in the world with no religious setting to put them in to make it all OK,” Lehmann Imfeld said. “I started to realise that the Victorians’ theological outlook was more complicated than that.”

As her research gained focus, Lehmann Imfeld realised that most literary scholars were uncomfortable reading these stories through a theological lens.

“Within a university setting,” she said, “literature is a very secular subject. There’s this sense that if we use theology, we are almost buying into something, or making statements about our own beliefs.”

More

A new take on old ghost stories

Superstitious nonsense?

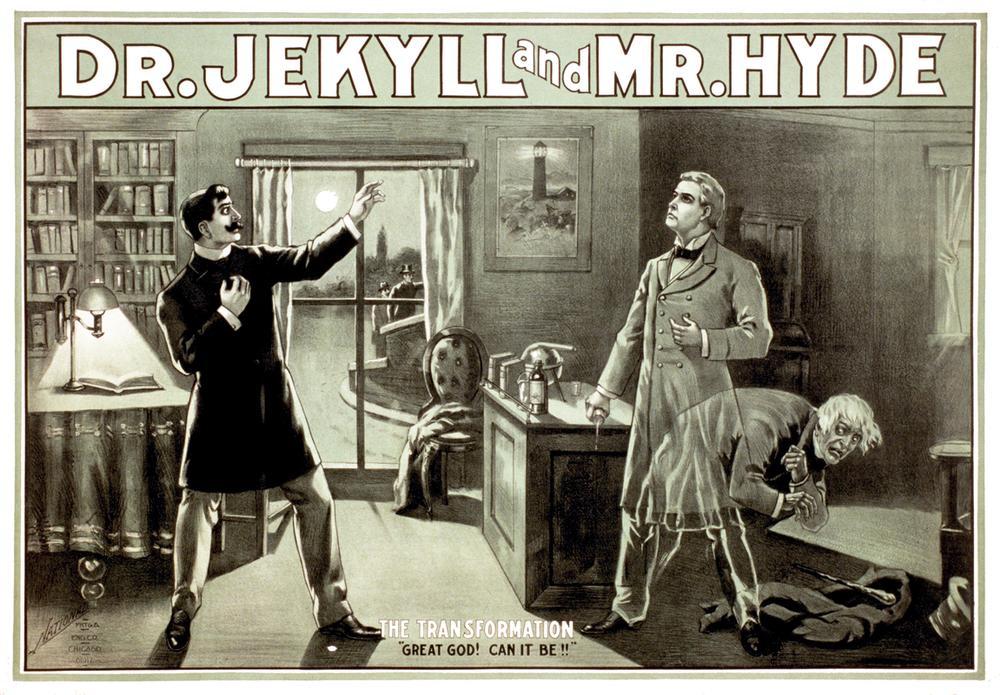

Lehmann Imfeld examined short stories from the late 19th century that typically feature an everyman protagonist, unlike the outsized, romantic characters of gothic ghost stories (Frankenstein’s monster, for example) that were more common earlier in the century.

“There is often a supernatural element that no one knows what to do with,” she said. “They set the stories against a backdrop of the everyday, which I think makes them even scarier.”

Typical of this genre, she said, are the short stories of Victorian author M.R. JamesExternal link, who specialised in a bumbling, academic type of main character with a knack for stumbling on supernatural objects he should not disturb – but, of course, does so anyway, to his own peril.

“It’s this idea of reclaiming superstition and taking it seriously again,” Lehmann Imfeld said.

“[These characters] actually think in a way that is similar to how we think today: that science is so far along that there is very little that they cannot explain,” she said. “They are quite confident that they have it all worked out. But then they are confronted with something that shows them that they really don’t.”

From Victorian England to outer space

Since defending her doctoral thesis with distinction in 2015, Lehmann Imfeld has become an interdisciplinary postdoctoral researcher with the University of Bern’s Centre for Space and HabitabilityExternal link.

Rather than studying the supernatural, she is building on her research now by looking at how people cope with the unknown in the realm of science – particularly in astrophysics.

“I’m especially interested in questions of how to define life on other planets: does it have to be a creature, or even carbon-based? Could it be silicon-based?” she asked. “Then I’ll look at science fiction works to see how they have imagined possible answers to those questions.”

She sees many parallels between this project and her previous work on the supernatural, particularly in how people confront the unknown.

Theology as a tool

Lehmann Imfeld’s doctoral research will be published this summer as a book entitled, “The Victorian Ghost Story and Theology”. Despite the impact of her work on literary theory, she emphasises that she is a strong supporter of people reading ghost stories in any way they choose. She does not believe that all horror literature should be viewed as theological.

“When we read literature, especially the older works, we don’t tend to have these theological ideas in our vocabulary – we are usually more comfortable leaving them to the theologians – but then I think you miss out on reading what’s in these texts,” she said.

“So, my hope is to reintroduce some of that vocabulary; to say that it’s OK to use theology as a tool to understand what you are reading, without making ideological statements.”

Supernatural Switzerland

According to Switzerland’s Federal Office of CultureExternal link, ghost stories play a particularly key role in Central Switzerland’s oral heritage, and usually involve a phenomenon such as a sound, movement or visual apparition that has no rational explanation. Supernatural events in these stories are typically set in a real place or everyday surroundings, and are, the website claims, witnessed by “real people, either living or deceased (in contrast to the protagonists of most legends, whose historical authenticity is doubted).”

Switzerland’s ghost story tradition tends to be strongest in rural regions of the country, making the city of Zurich’s long list of paranormal legends unusual. Visitors can learn about them during the famed Ghost Walk of ZurichExternal link, where tour guide Dan Dent relates tales of the city’s reputed poltergeists, ghosts, and walking dead.

Until recently, Switzerland’s most famous haunted house was located in Stans, canton Nidwalden. According to the Historical Dictionary of SwitzerlandExternal link, it belonged to Melchio Joller, a Swiss lawyer born on January 1, 1818. In 1862, Joller began experiencing “mystical visions“ of ghosts in his house, which eventually forced him to leave the town. The supernatural phenomena, which have never been explained, inspired a 2003 filmExternal link before the house was torn down in 2010.

There appears to be growing concern with ghost stories and other paranormal activities, beyond just popular movies and music. French-language Swiss newspaper Le Matin published a feature in March describing the growing demand from real estate agents for “ghost hunters” to come and “cleanse” new homes and apartments before new renters move in.

The Marie Heim-Vögtlin prize and grant

The Marie Heim-Vögtlin (MHV) prize of CHF25,000 ($25,880) is awarded annually to one recipient of the Marie Heim-Vögtlin grantExternal link in recognition of excellent research quality and progress.

The Swiss National Science Foundation awards about 35 MHV grants annually to female doctoral and postdoctoral students at Swiss institutions, who have had to interrupt or reduce their research activities due to family commitments. Recipients receive salary support for up to two years, and the grant can also be used to cover research and childcare costs.

Both the MHV grant and prize are named for Marie Heim-Vögtlin (1845-1916), Switzerland’s first female physician, and co-founder of the first Swiss gynaecological hospital in Zurich.

Do you have a favourite ghost story from your country or culture? Tell us in the comments section below.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.