‘Scientific diplomacy is a must, not a fad’

A Swiss scientific and diplomatic project to safeguard and study the Red Sea corals, which are particularly resilient to climate change, has resumed in Sudan after a brief hiatus. SWI swissinfo.ch met the project’s leader, Anders Meibom of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL).

Half the oxygen we breathe comes from the oceans and 80% of the planet’s life is found there. The waters also absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and act as a global air conditioner.

However, the seas are also changing and suffering as a result of human activity, jeopardising the balance on which our very existence depends.

The international community and scientific world are working to safeguard the oceans from the combined threats of climate change, pollution and overfishing. Despite covering 70% of the earth’s surface, only 2% of all waters are properly protected from the most destructive human activities. UNESCO’s target of increasing this to 30% by 2030 is still a long way off.

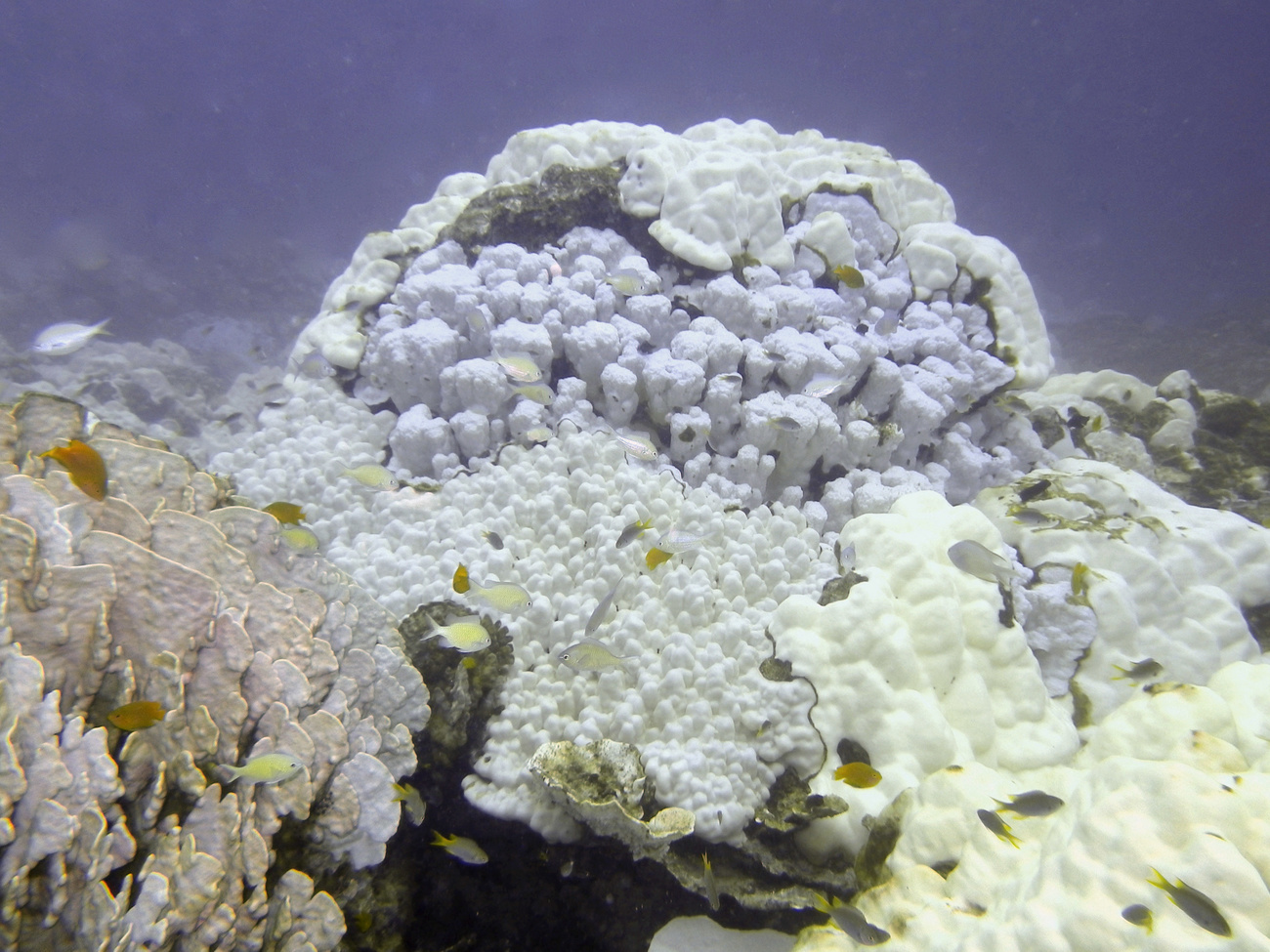

At a regional level, however, steps are underway to protect the most valuable marine ecosystems. One of these is being carried out by the Transnational Red Sea CenterExternal link (TRSC), set up within EPFL to fathom and preserve the secrets of the Red Sea reef, in particular that of the Gulf of Aqaba, whose corals have proven particularly resistant to climate change. It is a project that demands considerable diplomatic effort, as it requires cooperation between the states bordering the Red Sea, which are often not on friendly terms.

More

Diplomacy and science working hand in hand

Despite an accident that led to the early grounding of the mission’s sailboat-laboratory, the Fleur de Passion, the project is continuing. During the GESDA science and diplomacy summit, SWI swissinfo.ch met the Danish director of the TRSC, professor of biological geochemistry at EPFL Anders MeibomExternal link. He had just come back from Sudan, where he was conducting surveys, together with researchers from Port Sudan’s Red Sea University, in preparation for the resumption of the scientific expedition proper next year.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Geopolitically, the Red Sea region is both complex and delicate. What motivates the different countries to work together on this project?

Anders Meibom: I think there is clear awareness in the region that the coral reef and the ecosystems it represents are of huge interest for the individual countries. We should remember that it is not just a question of biodiversity – although this is very important, of course – but also of the services that this ecosystem provides to the people living around the Red Sea, in terms of both fishing and tourism revenue. Marine tourism is an essential source of income, and it is clear that if the coral reef were to die and the ecosystem collapse, the economic impact would be enormous for every single country in the region.

SWI: What will happen to the data you collect?

A.M.: The scientific work we plan to carry out – and I wish to emphasise that it is being done in direct collaboration with scientists in the region; after all, it is their coral reef and they already know it very well – will be fully shared according to the principles of open science. This is an absolute must. If we want to be able to discuss the best ways of protecting the reef, everyone must have access to the same data and achieve the same level of information. Our work would not make sense if we did not share the findings efficiently.

In addition to open science, a very important part of the project is training the next generation of scientists, who will be taking up the mantle.

SWI: Don’t you think that some countries may be unwilling to share data with states with which they have unfriendly relations?

A.M.: This is potentially true. It is all a question of building trust. Switzerland and the TRSC are organising the scientific work and creating a central database to distribute the findings. It is clear that the project is in everyone’s interests and is being carried out by a country like Switzerland, which has no particular strategic stakes in the region, but is simply there to help: to help the region and all of humanity save one of the most unique reef systems in existence, and which will probably be the last one left by the end of the century.

We hope, and indeed we expect, that the presence of this neutral partner will prompt the different countries to agree to the sharing of data.

SWI: What are the main risk factors for oceans today?

A.M.: There is of course the big factor of global warming and acidification of the oceans, mainly as a result of CO2. We should bear in mind that even if human CO2 emissions ceased today, the planet would continue to heat up for a long time, as the system has great inertia.

But then there are also local factors, for instance sources of pollution, which the different countries can control within their own territory. And here there is huge scope for improvement.

SWI: So what can be done?

A.M.: On a local scale it is possible to act quickly, and individual states can do something. Taking the example of coral reefs, steps can be taken to stop their misuse and mismanagement and to stem overfishing and destructive fishing practices. Better forms of tourism can be promoted that are more respectful of the environment.

All of this requires knowledge, supervision and implementation. Of course it is difficult, but it can be done.

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!