Sponge could clean up future oil spills

A Swiss-developed sponge that one day could take on oil spills like the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster of five years ago has taken a step closer to industrial use.

The Deepwater Horizon spill deposited an estimated 16-20 million gallons of oil on the floor of the Gulf of Mexico, including what scientists have called a “bathtub ring” some 3,200 square kilometres in size, according to the resultsExternal link of different studiesExternal link.

Such “mats”, reportedly formed after chemical dispersants Corexit 9500 and 9527 solidified the oil before dropping it to the ocean floor, deprive subaquatic areas of oxygen, rendering it more difficult for bacteria to decompose the oil. And pieces of these toxic mats regularly appear on shorelines and beaches following strong weather fronts.

Exactly five years after the world’s biggest marine spill, oil production is again at full throttle in the gulf, with nearly 4,000 oil and gas platforms located there.

If there is a new spill in the region, or elsewhere, the sponge developed by Switzerland’s materials science lab (EMPAExternal link) could be deployed in the clean-up and help prevent the kind of long-term negative impact caused by the use of chemical dispersants.

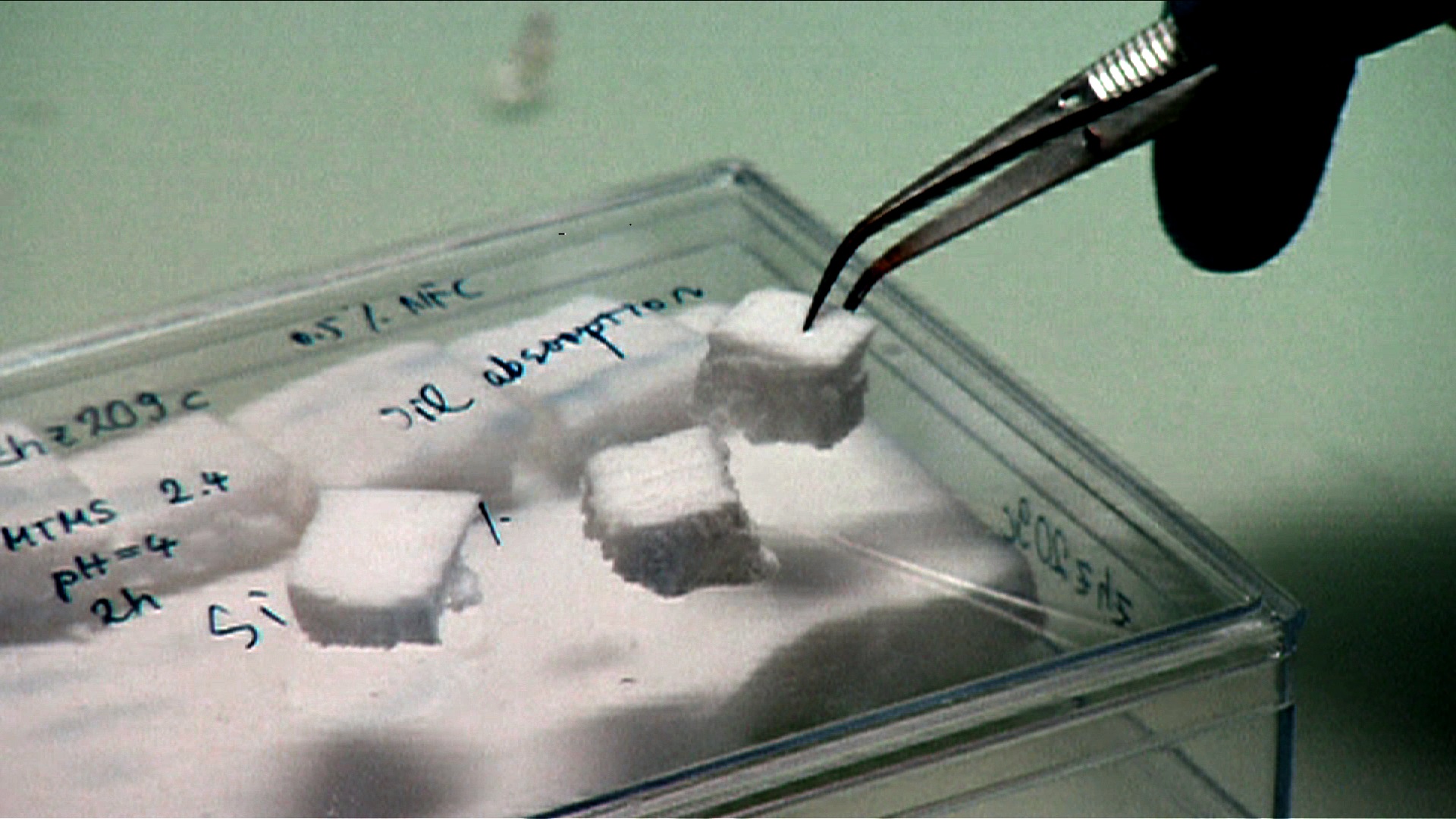

EMPA’s highly absorbent material separates oil from water and can hold up to 50 times its own weight. Once soaked, it continues to float, making it easy to recover and recycle.

More

The sponge that can fight oil pollution

“The sponges can be easily cleaned with an organic soap and reused directly, which makes it interesting,” EMPA researcher Philippe Tingaut told swissinfo.ch.

To produce the sponge, cellulose materials such as wood, plants or recycled paper are specially ground into fibres to create a distinctive pulp, and then mixed with water. Tingaut’s colleague Tanja Zimmermann explained that when the combination is freeze-dried, a bonding of chemical compounds occurs, creating a sponge with large surface areas and high absorbability.

Once EMPA made its invention known, it didn’t take long to stir interest in the industrial sector.

Wicor Holdings, the world’s largest maker of cellulose-based materials for major power transformers, partnered with EMPA in November to develop the sponge further.

The company has begun to manufacture cellulose batches to be used in the sponge’s trial stage. Wicor will also be refining the grinding process for cellulose and the subsequent chemical process to manufacture the absorbent.

Wolfgang Exner, senior vice president at the Rapperswil-based company, said Wicor’s interest came from the need to develop special materials used in electrical insulation of power transformers. Transformers are often filled with oil, and require materials that do not absorb humidity from the air or water, which would alter the materials’ dimensions or sizes.

But Wicor aims eventually to scale up production for practical use in oil spills.

Exner said that while the project was still in the early developmental stage, “the final cost-performance ratio will make the sponges very attractive for continuous use in various industries as well as for emergency application”.

The firm is currently in contact with oil companies “on the technical side”, Exner explained, servicing and controlling their electrical transformers. But “if they demand to obtain [the oil sponge], we will manufacture it, possibly in the US”.

EMPA’s partnership with Wicor is expected to last two years.

The oil sponge could also be put to good use on lakes. Zurich’s cantonal lake police have already been in contact with EMPA to enquire about the sponge for use on unsightly oil spills.

Fire brigades could deploy it to clean up smaller spills from overturned trucks or leaks from building sites where oil can enter drains and eventually the lake.

Lessons from 2010

On April 20, 2010, a fatal blast on BP’s Deepwater Horizon rig, owned by Zug-based Transocean, claimed the lives of 11 workers. Three months of uncontrollable gushing from the Macondo well left nearly five million barrels of oil (210 million gallons/780,000 m3) in the Gulf of Mexico, according to the US government.

A month after the start of the massive spill, and following graphic images in the media portraying its magnitude and effect on coastal wildlife, BP began spraying a chemical dispersant, Corexit, from planes, and directly onto the source of the leak.

At the time, the government gave BP a 24-hour ultimatum to offer a less toxic alternative or a report explaining why Corexit would be preferable, with the company choosing the latter option. The chemical was immediately available in large volumes and quickly deployable.

Corexit breaks down oil molecules, solidifying them into droplets that then fall below the surface of the water. Scientific studies argue that Corexit amplifies the toxicity of oil, while local residents, clean-up workers and doctors have claimed it is responsible for pathogens such as acute rashes, eye irritation, and damage to the kidneys and the liver, just as the manufacturer’s product label warns. Gulf fishermen reported falls in shrimp and oyster populations, and deformations of species due to the massive use of the dispersant. Approximately 1.84 million gallons of the chemical were used on the spill.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.