Glaciers and the changing landscape in the Alps

The Alpine glaciers are disappearing due to global warming. If they all go, the look of the Alps will change for good. Researchers are trying a range of technological solutions to stop the ice melting.

When Switzerland was covered by a blanket of white at the beginning of May this year, with snow right down into the valleys, there were many here who raised their eyes to heaven in disbelief. Farmers feared for their crops, and drivers feared that their summer tyres might not hold up.

But for Felix Keller, a glaciologist, the freak weather spell was like manna from heaven. As he told swissinfo.ch, the exceptional snowfall prolonged the Alpine winter, giving the glaciers a bit of extra respite from the sun’s rays.

From the top of the Alps right down into the valleys, this swissinfo.ch series explores the effects of the melting of glaciers at different altitudes, and the strategies being adopted in Switzerland to try to cope with the problem.

3,000 – 4,500 metres: Alpine glaciers and the landscape

2,000 – 3,000 m: tourism and natural hazards (to appear in September)

1,000 – 2,000 m: power generation (to appear in October)

0 – 1,000 m: water resources (to appear in November)

Despite the unusually heavy snowfall in late spring, the glaciers continued to melt. Two heatwaves that hit Switzerland between the end of June and late July, with around 30 degrees Celcius recorded in Zermatt at the foot of the Matterhorn, just made things worse.

In 14 days of high temperatures, Alpine glaciers lost about 800 million tonnes of snow and ice, tweeted Matthias HussExternal link, who heads the network Glacier Monitoring SwitzerlandExternal link. Imagine it as a cube of ice three times higher than the Eiffel Tower – or the quantity of drinking water consumed by the Swiss population (8.5 million people) in the space of a year.

Not a glacier left by 2100?

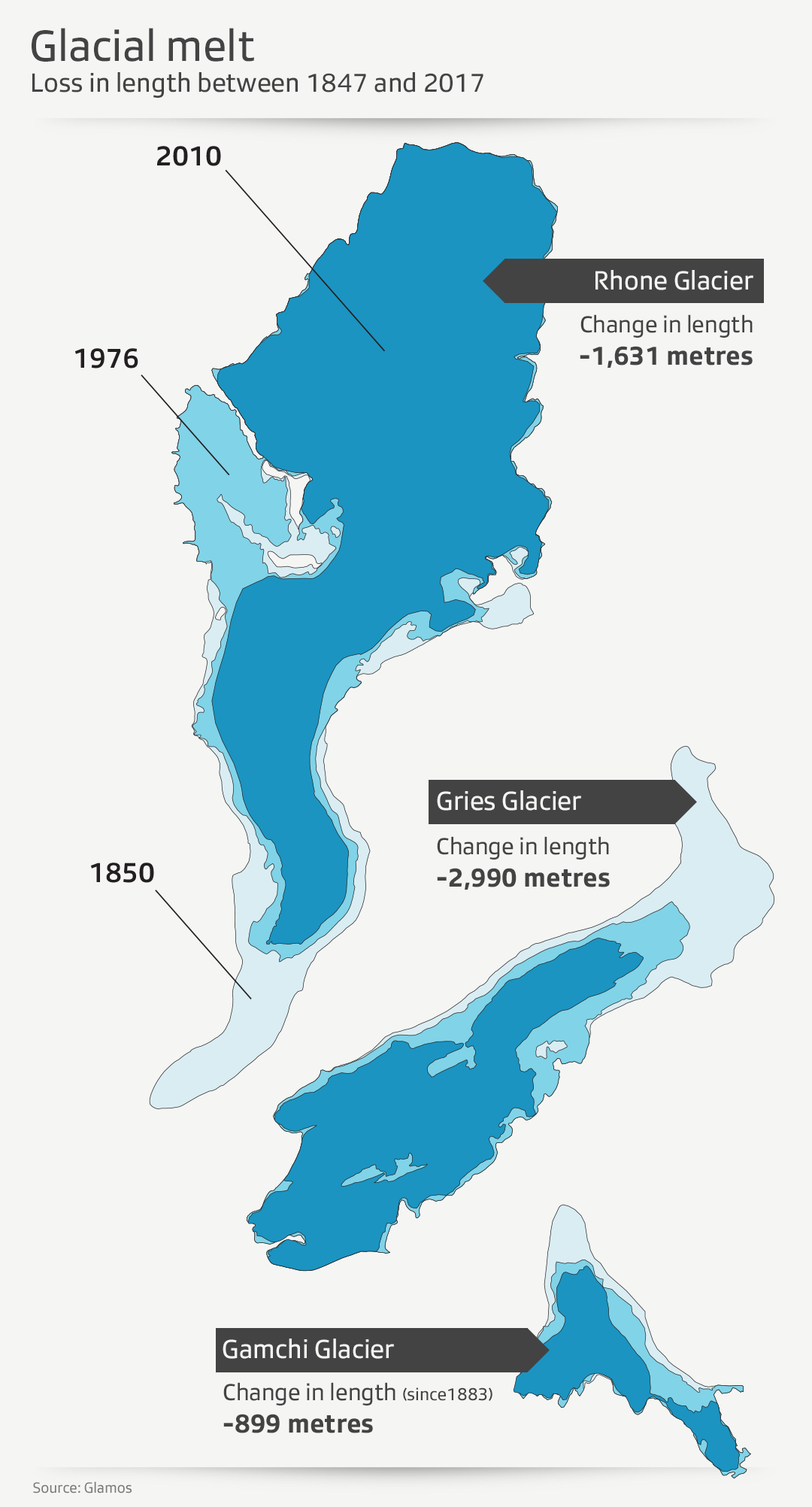

The fact that glaciers are melting is not exactly news: since 1850, the volume of Alpine glaciers has declined by about 60%. What is surprising to observers is the pace at which these giants of the Alps are now shrinking.

“The impression I get is that in the past ten years the pace of the melting of glaciers has increased considerably”, Simon Oberli writes on his website. He is a nature photographer who documents the phenomenon with spectacular panorama shotsExternal link.

+ Find out what’s happening to the longest glacier in Europe

Huss agrees that the melting process has gathered speed since 2011. In the hydrological year 2017-2018 alone, the 1,500 Swiss glaciers lost 2.5% of their total volume External link.

At this rate, half of the Alpine glaciers are likely to disappear altogether in the next 30 years, says a recent studyExternal link by the Federal Institute for Technology in Zurich and the Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research. If nothing is done to bring down greenhouse gas emissions, every single glacier in Switzerland and in Europe is likely to melt away by the end of the century, the scientists warn.

Alps will look different

The effects of the retreat of glaciers in Switzerland, a country particularly affected by global warming, are several. Depending on the altitude, they can be physical, geographical or economic. The sectors being affected are tourism, hydro-electric power, prevention of natural hazards, and water resources.

In the country’s highest regions, between 3,000 and 4,500 metres, the reduction of the ice mass is changing the Alpine landscape irrevocably. Along with the glaciers, a piece of national identity is being lost, a frame of the picture the world has of Switzerland. According to the Swiss branch of WWF, with their disappearance “the look of the Alps will never again be what it was”.

Switzerland is also losing “sites of national importance”. 62% of Swiss glaciers are listed in the federal inventory of landscapes, sites and natural monumentsExternal link. With the retreat of the glaciers, “a part of our history is disappearing”, says Green parliamentarian Lisa Mazzone.

Can the glaciers be saved?

Ideas for slowing down the melting of glaciers are already being tried. For over ten years now the Rhone glacier in Valais has been covered in white sheets designed to protect it from the sun’s rays. The prime goal is to preserve the ice grottoExternal link, one of the Alps’ great tourist attractions.

This approach is useful on a small scale where the aim is to slow melting at a local level for economic reasons, comments Huss. “However, it is not designed to save a whole glacier. The costs would soon exceed the economic benefits. And I can’t help wondering myself whether tourists really want to see blocks of ice wrapped up in grubby sheets”.

Swiss glaciologist Felix Keller has come up with a different idea: recycling water from ice melt that flows down from the glaciers during the summer. “We could preserve large quantities of it and turn it back into ice for the winter – or even use it to produce artificial snow, the best possible protection for a glacier”, he told swissinfo.ch.

In fact, Keller wants to install a snow-generating system above the glacier that is off the ground and requires no electric power. To have an effect, this kind of apparatus, which has been patented by a SwissExternal link company, would have to produce 30,000 tonnes of snow a day. “My partners believe it can be done”, says Keller, who heads the project.

A pilot project costing CHF2.5 million ($2.5 million) started in August on the Morteratsch glacierExternal link in the Grisons, and it will go on for 30 months. With support from the Swiss Agency for the Promotion of Innovation and a number of research institutesExternal link and industrial partners, Keller hopes to arouse interest in his idea not just in Switzerland, but in other parts of Europe, in the Himalayas and South America.

The method is an interesting one, Huss finds. “The technological challenges, the overall costs and the environmental implications are enormous, though”, he cautions.

Prayer and human effort

There are even appeals to divine providence to save the glaciers. With authorization from the Vatican, two Valais communities have altered the wording of an ancient prayer that the spread of the Aletsch glacier be kept within bounds – it was the biggest on the continent of Europe – so as to reduce the risk of flooding. Since 2011, they have been praying that this UNESCO world heritage site be preserved from global warming instead.

Huss, however, puts his faith in human efforts. “The glaciers can be saved, but only with global action on climate protection.” If we could limit global warming to two degrees, he says, by the end of the century we could still preserve a third of the present volume of Alpine glaciers.

Launched in 2019 by the Swiss Association for Climate Protection, the people’s initiative “for a healthy climate” ( External linkGlaciers Initiative) calls for reducing net emissions in Switzerland to zero by 2050 and for the objectives of the Paris climate agreementExternal link to be enshrined in the federal constitution. The campaign looks like getting the requisite 100,000 signatures and will then be put to a nationwide vote.

Translated from Italian: Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.