Swiss “janitor satellite” to clean up space

Swiss scientists plan to launch a mini satellite fitted with jellyfish-like tentacles that can clear some of the huge amount of debris orbiting above our heads.

Researchers at the Federal Institute of Technology, Lausanne, (EPFL), hope the SFr10-million ($11-million) CleanSpace One prototype satellite will be in the skies by 2016 in a bid to help resolve the worsening space junk problem.

“It’s time to do something to reduce the amount of debris floating around in space,” Swiss astronaut and EPFL professor Claude Nicollier told reporters in Lausanne on Wednesday.

After two years of research scientists working on the CleanSpace One project aim to build the first prototype in a family of clean-up satellites.

Their initial space mission will be to target and de-orbit one of two Swiss satellites – the SwissCube or the TIsat, launched in 2009 and 2010, respectively.

A number of other organisations, including the German, Russian and European space agencies and Nasa, are also working on this international space debris problem but the Swiss hope to be the first to become operational.

Technical challenges

However, many challenges lie ahead.

The first involves propulsion. Once launched into space the 30cm-by-10cm-by-10 cm “janitor” will have to adjust its trajectory to precisely line up with the target’s orbit using a new ultra‐compact motor being developed at the EPFL.

Then when it approaches one of the junk satellites – travelling at 28,000 km/h, 600‐700 km above the Earth’s surface – CleanSpace One will then have to grab and stabilise it.

Inspired by the animal and plant world, the team plans to develop a tentacle-like gripping mechanism to help it hold on to the spinning object.

“Nature has a way of being very energy efficient. If you think of the jellyfish or anemone they can catch objects of different shapes which are tumbling or passing by. We will use them as examples,” Muriel Richard, deputy director of the Swiss Space Center, told swissinfo.ch.

Finally, once the janitor has secured the piece of junk, it will “de-orbit” the redundant satellite by firing up its engines so that both fall back together into the Earth’s atmosphere, burning up on re‐entry.

Not a one-off

From launch to destruction the whole process should take six months.

Although the prototype will be destroyed on its first mission, the CleanSpace One project is not a one-off.

“We want to offer and sell a whole family of ready‐made systems, designed as sustainably as possible, that are able to de-orbit several different kinds of satellites,” explained Swiss Space Center Director Volker Gass.

“Space agencies are increasingly finding it necessary to take into consideration and prepare for the elimination of the stuff they’re sending into space. We want to be the pioneers in this area.”

Tipping point

The international space community agrees that the space junk problem has become critical.

Since Sputnik 1 was launched in 1957, there have reportedly been 4,700 launches which have put 6,000 satellites into orbit. But only 800 are still thought to be operational, 200 have exploded in orbit and every year 100 new satellites are put up in space.

“When you are up in space you are initially struck by its beauty and spotlessness, but this first impression is misleading,” said Nicollier.

In fact, over 600,000 pieces of space litter are currently orbiting the Earth, mostly at an altitude of 300-900 kilometres. The debris includes parts of jettisoned rocket stages, abandoned satellites, solar cells, paint flakes and solid fuel.

“Most debris comes from satellites that are no longer in use – typically they have run out of energy and their solar panels or batteries don’t work; when they collide it creates lots of debris,” said Nicollier.

Space scientists agree that the major risk is not to humans on Earth, as most debris burns up on re-entry, but to space missions and satellites.

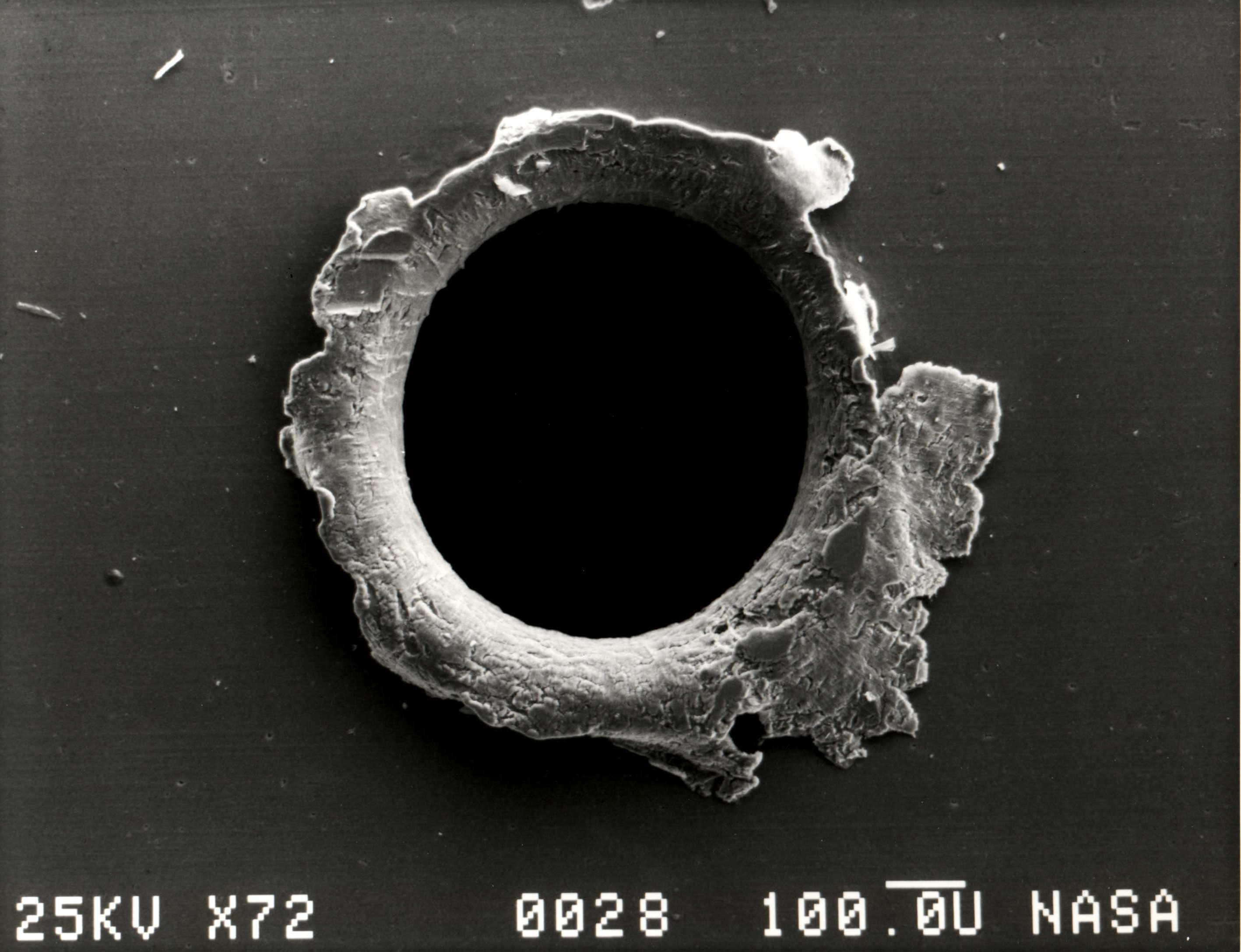

All but 16,000 objects in this huge field of space junk are smaller than a tennis ball. But with debris zipping around the globe at breath-taking speeds of up to 35,000km/h, collisions with satellites and other spacecraft – even involving small pieces – can be dramatic and generate huge costs for operators and insurance companies.

“If you look at the sheer amount of uncontrollable debris it’ll grow exponentially. If we don’t do anything now we won’t be able to put satellites in orbit for meteorology, GPS or telecommunication purposes,” EPFL scientist Anton Ivanov told swissinfo.ch.

In 2006 Nasa, which is monitoring the larger debris, released a study showing that a critical space junk tipping point was approaching. It is agreed that five to 15 pieces of large debris have to be removed annually starting in 2020 to prevent the situation from spinning out of control.

The US Space Surveillance Network monitors around 16,000 pieces of debris larger than ten centimetres. But the majority of debris objects remain unobserved.

According to a European Space Agency (ESA) model, there are more than 600,000 objects larger than 1cm in orbit. Information on space debris is collected by US, Russian and European radar and optical systems and used to validate models of the debris environment.

In collaboration with the ESA, Bern University’s Astronomical Institute has been tracking space junk and carrying out space debris surveys over the past ten years.

The five-person Swiss team uses optical telescopes located in Tenerife and at Zimmerwald, near Bern, to search for and monitor junk found mostly at high altitudes – 20,000-36,000km.

Switzerland was one the founders of the European Space Agency.

The Swiss space industry includes 28 research institutes and 54 companies.

They specialise mostly in ground equipment, optical apparatuses, telecommunications systems, clocks, robotic machinery, microgravity research and weather surveillance.

Switzerland’s Claude Nicollier is an astrophysicist, test pilot and astronaut.

He was the first foreigner granted mission specialist status by Nasa and completed four missions on board the space shuttle. His first shuttle mission was with the Atlantis.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.