Anthills yield insights into evolution of society

You may think twice before stepping on an ant after reading this article. Evolutionary biologist Laurent Keller, who has been awarded Switzerland’s top scientific prize, has spent his career showing how surprisingly like us the social insects are – in behaviour and organisation.

From agriculture to the division of labour, the achievements of ant society have predated those of human society. Keller, head of the department of ecology and evolution at the University of Lausanne, believes knowing more about ants can help us understand some of our own behaviours and how we interact with others.

“In terms of social organisation, man has taken the same route as the ant,” says Keller, who is due to receive the Marcel Benoist Prize in a ceremony on Monday.

Observing ants, even following them individually, is what Keller has been doing for the past 30 years, both out in the field and in the biology lab. He originally wanted to study the great apes, but hearing a lecture on ants made him change his mind.

“I was fascinated by the evolution of their social organisation,” he tells swissinfo.ch.

Today Keller is among the world’s foremost myrmecologists – ant experts to the rest of us – with his publications appearing in the most prestigious scientific journals. What still intrigues him is one question: how did an organism with a really simple brain manage to adopt social behaviours that have allowed it to expand successfully all over the earth, from the Sahara to the coldest regions?

Ant police

In the entire animal kingdom, ants – of which about 12,000 species have been identified – are among the most important organisms from an ecological point of view. They improve the quality of the soil, facilitate distribution of seeds and get rid of parasites and dead organisms, Keller explains.

“This planet would be hard to imagine without ants. Their weight makes up 10% of the biomass of all land animals. The only one with a similar biomass is man.”

One of the keys to their ecological success, he continues, is social cooperation. “Ants have succeeded in changing their environment, for example constructing complex nests on the ground or up in trees. With their division of labour, they have been able to increase the productivity of the group. They have also developed mechanisms for reducing conflict and limiting the spread of parasites within the colony.”

There are even ant police whose job is to remove workers whose behaviour is harmful to their society.

These are all features found in human society, Keller points out. “Like the ants, we have modified our environment by building cities that protect us from nature and predators. We specialise in particular tasks, which has helped us increase our productivity.”

The analogies between humans and ants are indeed astonishing. It is hard to believe that some of the greatest inventions of humanity had already been made by a creature a few millimetres long – 70 million years ago.

More

The ant’s best friend

Ants as farmers

To feed their colonies, which may comprise up to five million members, ants invented agriculture and livestock raising, Keller explains.

Some species grow fungi and boost their growth with enzymes. They raise aphids (greenflies) which they move from one tree to another to graze. The ants consume their honeydew, a sugary substance rich in amino acids, and in time of need they eat the aphids themselves.

“Just like man with his cattle: he drinks their milk and eats their meat.”

Keller says the way ants communicate and choose a route when gathering food is a source of inspiration to modern information technology.

“There are computer programmes that are modelled on the behaviour of ants. They help solve the ‘travelling salesman problemExternal link’ and establish the shortest route to get around a set of different points.”

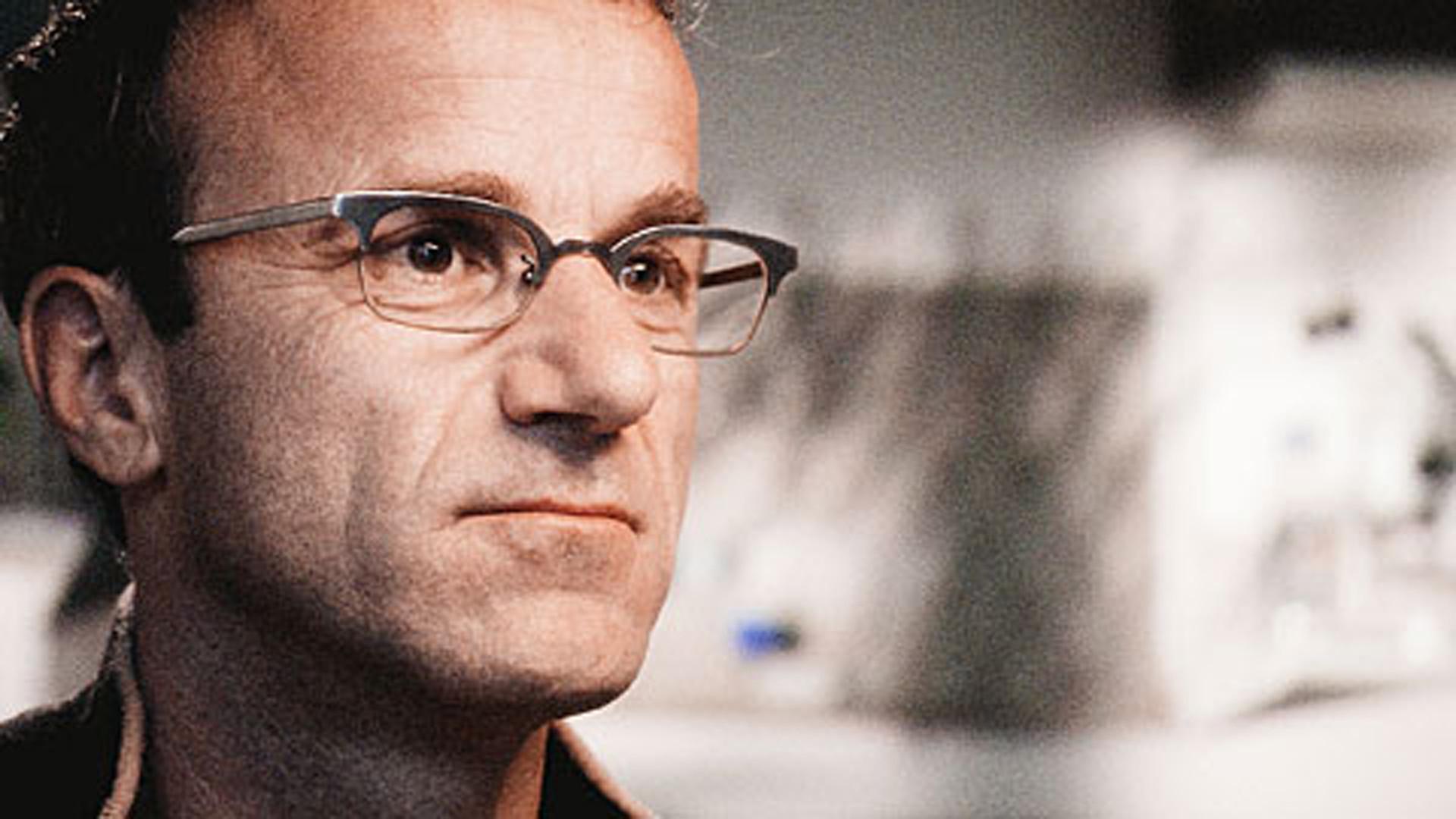

Laurent Keller

Director of the department of ecology and evolution at the University of Lausanne, Keller is one of the most renowned researchers in Switzerland in the field of evolutionary biology.

Keller studied biology at the University of Lausanne, where he obtained his PhD with distinction in 1989.

Ants are the subject of his research. His ground-breaking experiments have greatly helped to improve our understanding of natural selection and the social behaviour of animal communities. The findings from this research enable us to draw parallels with human cohabitation such as how people cope with stress or the ageing process. From his theoretical work and primarily his experimental research, he has helped drive subsequent development of this research field. Among other things, he has authored several popular science books and articles.

(Source: Marcel Benoist foundation)

One of the most fascinating aspects of the discipline for Keller is the exceptional longevity of ants. In some species, queens live for up to 30 years – “100 times the insect average”.

Protected by workers, queens run less risk of attack by predators. In the course of evolution, this life shielded from danger has allowed the development of DNA repair mechanisms which slow down the ageing process. “This is a good model for studying ageing in humans,” Keller notes.

Imaginative and restlessly eccentric, the 54-year-old scientist wanted to push beyond the frontiers of biology. In collaboration with the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), he has studied the behaviour of miniature robots programmed like ants.

“We found that the robots operate on the same principles of natural selection. They are more effective as a group than when they work alone,” he says.

Facebook for ants

The first scientist to sequence the genome of the fire ant (Solenopsis invicta), Keller is also interested in the genetic bases of behaviour.

“We discovered the existence of a ‘social chromosome’, which explains how some colonies have just one queen while others have several.” This discovery could, he thinks, be useful in combating very large colonies that are a nuisance to farmers in the US, Australia and China.

Apart from contributing to studies of longevity, Keller now focuses his research on how the division of labour is regulated in the colony. For this purpose he has been sticking tiny barcodes on the backs of hundreds of ants. For 41 days, a scanner has been recording the behaviour of each insect, providing information about who interacts with whom, where and when.

“This is a kind of Facebook for ants,” he comments drily.

The initial results, published in the journal ScienceExternal link in 2013, showed that the tasks of ants evolve over their lifespan. “The younger workers tend the eggs laid by the queen, while the older ones keep the nest clean and bring in food supplies,” he explains. Now the question is to find out how and why.

Ants, he says, are really an ideal model to study the evolution of life in society. “If we want to avoid a return to obscurantism [opposition to new knowledge],” he said some years ago, “it’s essential to know the ins and outs of evolution, among ants just as much as humans.”

Marcel Benoist prize

The Marcel Benoist Foundation for the promotion of scientific research was founded in 1920 by the Swiss government to execute the last will and testament of Marcel Benoist (1864-1918), a French national living in Lausanne who unexpectedly left most of his wealth to Switzerland on condition that it be used to fund an annual scientific award.

Considered the “Swiss Nobel Prize”, it’s the oldest award of its kind in the country. This year’s prize money is CHF50,000 ($51,500).

Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.