Switzerland seeks international recognition for those with vocational skills

Vocational qualifications - a pillar of the Swiss educational system - suffer from a lack of recognition abroad. But this could change if Switzerland introduces Bachelor’s and Master’s titles for professionals.

The State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI)External link is considering whether to give new names to Swiss higher professional qualifications in order to boost their value on the international jobs market, the SonntagsZeitung reported on June 20.External link Under discussion is the creation of two qualifications: “Bachelor Professional” and “Master Professional”

SERI has launched a special project to conduct “a holistic review of the current national and international positioning of the colleges of higher education as well as their educational programmes,” SERI confirmed to SWI swissinfo.ch.

The aim is to see whether titles such as a Bachelor and Master Professional -which would be obtained at a college of higher education rather than a university- would be viable on the international scene.

Impetus has come from neighbouring Germany, which also has a strong apprenticeship system. At the beginning of 2020 it introduced a “Bachelor Professional” and “Master Professional”. In Switzerland, several motions have also been introduced to parliament – including the most recent Aebischer motion – which argue that the Swiss are being disadvantaged internationally – and at home – by not having recognised titles.

Aebischer specifically calls for the government to look into “modern titles” which would “establish title and level equivalence with other title designations both at home and abroad (“Professional Bachelor”, “Professional Master”).”

Why?

The Swiss regularly score top marks in international vocational skills competitions, so why is this change being considered?

More

Young Swiss professionals shine at WorldSkills

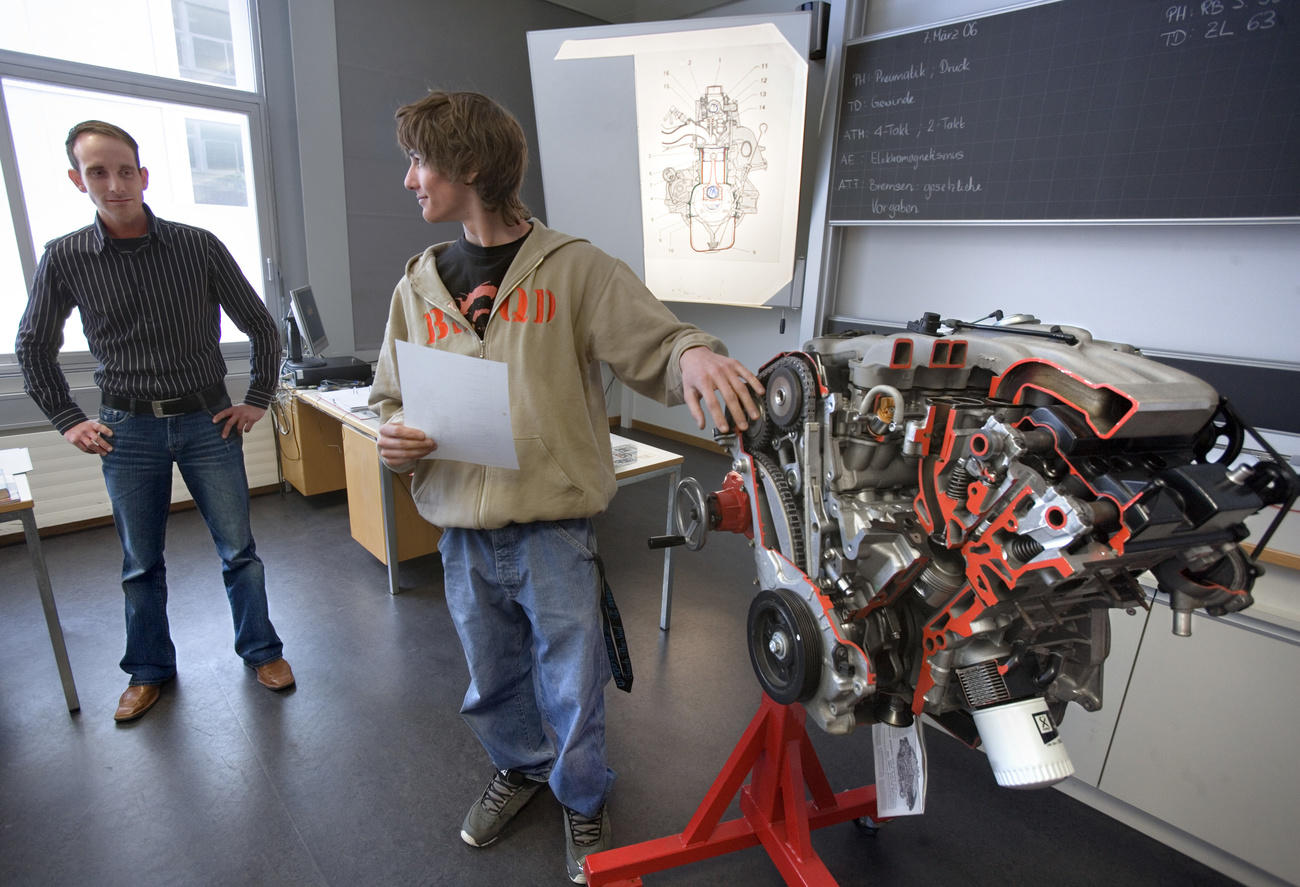

The answer lies in how the Swiss education system is set up. Around two thirds of Swiss school leavers go into vocational education: mostly an apprenticeship consisting of on-the-job training combined with vocational school. After two to four years they graduate with direct access to the job market. Youth unemployment in Switzerland is generally quite low (around 8% in 2020) compared with other developed countries.

There are then several paths for continuing their education: taking the vocational baccalaureate allows students to study for a regular Bachelor’s degree at a University of Applied Sciences (UAS), Switzerland’s more practically orientated universities which are mostly attended by qualified apprentices. An extra exam is needed to attend an academic university (in general, only around 25% of young people attend academic university in Switzerland.)

More

Vocational baccalaureate system struggles to grow

Young people can also deepen their professional knowledge and management skills via advanced federal diplomas and colleges of higher education. This is known as professional tertiary education and is a Swiss speciality. The aim is to provide a highly skilled workforce in areas such as engineering, health, administration and tourism services. Around a quarterExternal link of young people who have taken an apprenticeship take this route.

These colleges are, however, not officially recognised by the Swiss authorities, but the 430 qualifications they offer are.

Gaining recognition

It is the very uniqueness of the Swiss educational system which is prompting change. In some professions, like IT or nursing, getting a higher qualification is well established. But there are issues with recognition, as pointed out by Aebischer in his motion.

Urs Gassmann, managing director of the Swiss Association of Graduates of Colleges of Higher Education (ODEC), explains it this way: “If you have someone trained in Switzerland who goes abroad as a machine engineer to build up a machine, or lead a project, they often encounter the problem that their advanced federal diploma doesn’t mean anything to English speakers,” he explained. He also confirmed that this can happen within international companies or hotel chains in Switzerland who are more familiar with or even require a Bachelor’s academic degree to work there.

That is why his organisation introduced a Professional Bachelor ODECExternal link for its members back in 2006, anticipating that the whole tertiary sector would eventually move towards Bachelor’s, Master’s and PhDs. ODEC would also support a move to a national Bachelor Professional.

Universities are, however not convinced about Aebischer’s motion. Swissuniversities, the sector’s umbrella organisation, told RTS on June 22 “Bachelor’s and Master’s titles are reserved for academia. Extending this to other types of education will cause confusion.”

The Swiss government has also come out against the Aebischer motion (his second: he introduced a similar one in 2012 which was rejected by parliament), pointing to work previously undertaken to clarify professional tertiary education – there are, for example, now official English translations for some titles – and the current work being prepared by SERI.

Change ahead?

Jürg Schweri, a professor at the Swiss Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (SFIVETExternal link) said that for a long time the official Swiss position was that Swiss higher professional education was stronger when considered as its own route with its own strengths.

The view was that academic-style titles could increase confusion between the different routes and diplomas instead of clarifying them and could give the impression of “downgrading” existing titles, which are well accepted in Switzerland in many professional areas. Plus these new titles would not be seen in the same light as an academic Bachelor’s and Master’s.

“However, the German move sets a standard because Germany is the largest and best-known example of a country with a strong vocational and apprenticeship tradition,” he told SWI swissinfo.ch in email comments. “If the German solution proves successful, it might prove difficult to establish a different Swiss solution when it comes to the international recognition of Swiss professional education degrees.”

Aebischer’s motion, handed in last year, is still to be debatedExternal link by the House of Representatives in parliament. Meanwhile, the SERI report into the Swiss colleges of higher ed and their diplomas is expected by the end of 2021.

(Edited by Virginie Mangin)

Some stats

There were 35,1000 students in Swiss colleges of higher education in 2019/20External link, according to the latest figures available, with the most popular courses being nursing, followed by management and administration and then childcare and youth services.

Statistics collated by ODEC for 2019/20External link, show some typical salaries per sector for higher vocational diploma graduates (part time study, less than 2 years after graduating). Highest: legal assistant: CHF101,800 ($110,500) per annum; lowest: nursing CHF63,700 p.a.

More

Swiss vocational training serves as a model for others

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!