Switzerland treads cautiously on embryo law

Switzerland is set to be one of the last European countries to authorise pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) of embryos. The proposed legislation is particularly restrictive to increase the chances of it passing a national vote.

In the area of medically assisted reproduction in general, Switzerland tends to have much stricter legislation than what was adopted 10 to 20 years ago by most European countries. Because of the demands of the direct democracy system – the necessary seal of approval from voters – Swiss parliamentarians must try to seek consensus solutions.

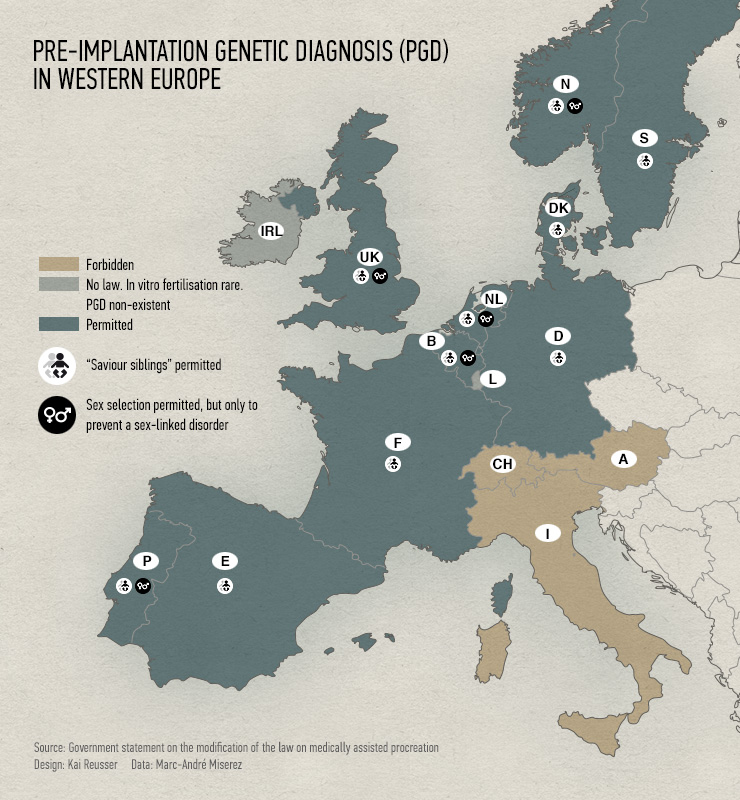

Austria and Italy are the only two other European countries to still have a ban in place on pre-implantation genetic diagnosis.

But things could soon change. After several attempts since the end of the 1990s, parliament finally accepted a motion in 2005 that asked the government to change the law to allow for PGD.

Members of the House of Representatives are unlikely to forget the impassioned plea made during the debate by parliamentarian Luc Recordon, born with Holt-Oram syndrome, who asked his colleagues for support “in the name of those children who like me would have preferred not to have been born”.

Eight years later, after a false start in 2009, the project for the modification of the law is finally wrapped up and ready for a decision by the electorate.

Recordon, now a member of the Senate, is still in favour of PGD. Although he finds the proposed legislation restrictive, he still welcomes the compromise, which is the only thing that can guarantee a majority in a popular vote.

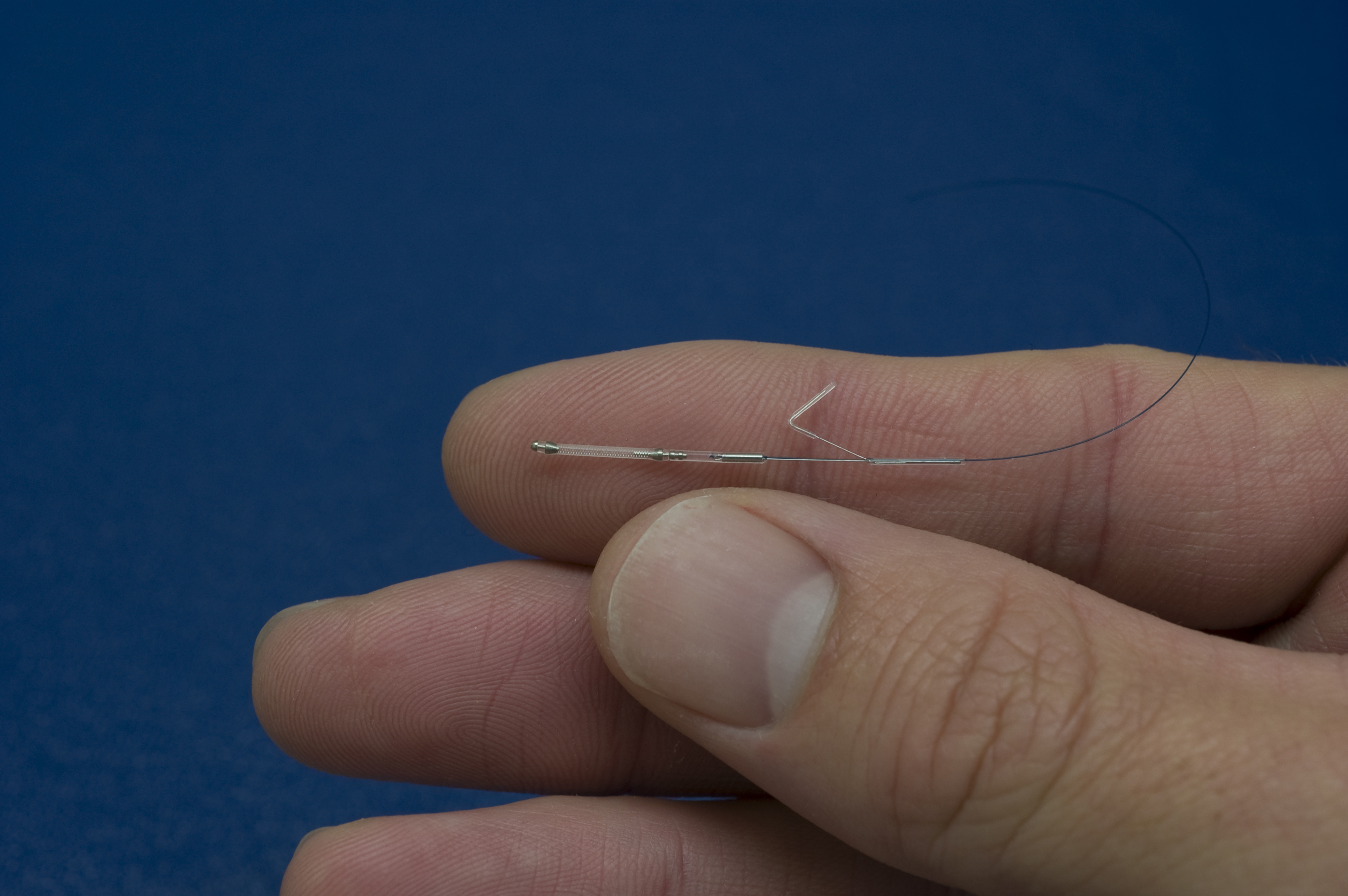

Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) is an analysis of embryos obtained through in vitro fertilisation before the embryos are implanted in the mother’s womb. It is used to detect serious defects and can lead to a decision not to implant an embryo.

Currently banned in Switzerland, PGD is a consideration for fewer than 100 couples per year. Today, the couples must either forego testing, or travel abroad for the procedure. This may change due to a proposed modification of the law on assisted reproduction. In June 2013, the cabinet asked the parliament to consider a proposal that provides for authorisation of PGD. Because this would involve a change to the constitution, the issue must undergo a popular vote.

The proposal remains very restrictive in comparison with the legislation of other European countries. PGD would only be possible if the couple risk finding themselves «in an intolerable situation” because the child conceived has a high probability of inheriting a serious genetic disease. Use of the testing in all other situations would be prohibited.

Up to eight oocytes per cycle could be cultivated to the embryonic stage, compared with three today. And it would be possible to freeze excess embryos for subsequent pregnancies. Currently, freezing of embryos is prohibited, and in the case of miscarriage the whole process must begin over again.

‘66% in favour’

“In Switzerland, we have a combination of several groups opposed to or to some extent distrusting PGD,” Recordon told swissinfo.ch.

“There is the Catholic fundamentalist movement, as well as the Protestants. There are those among the Social Democrats and the Greens who fear any overtones of eugenics. Also featuring is the lobby in defence of people with disabilities – primarily mental – who say that while we may have fewer handicapped children in the future, those parents who have them by choice or by accident are going to find themselves more isolated.”

François-Xavier Putallaz, philosopher, professor of theology at Fribourg University and member of the national ethics commission on the issue, also emphasises the essential search for compromise acceptable to a direct democracy regime. “We are I believe the only country that asks people what they think about this, and therefore we must find consensus, with the smallest common denominator. Elsewhere, these are parliamentary decisions, where majorities are still a little easier to find.”

Because it involves a change to the constitution, the authorisation of PGD requires a national vote. “It will pass by 66 per cent. I’ll put money on it,” Putallaz predicted, knowing he will be in the minority camp.

More

Switzerland among the ‘hardliners’

Slippery slope

What makes PGD unacceptable in the eyes of this philosopher? For Putallaz it is mainly the “slippery slope, on which, once the first step is taken, it becomes impossible to hold back others, all the way to the bottom of the ravine that we wanted to avoid.”

Having observed the evolution of legislation in other countries, like Spain or France, Putallaz has seen the barriers there fall one after another. Switzerland cannot avoid the same thing happening. He believes humanism calls for that trend to be resisted.

A trend which is illustrated by the following example: Switzerland plans to prohibit the practice of producing ‘sibling saviours’, children conceived to be immunologically compatible with an ill brother or sister so that they can donate bone marrow stem cells.

The consequence will be that “couples who cannot access this technology in Switzerland will go to France, Belgium, Spain. And only the rich will be able to pay, which is objectively unacceptable. Therefore, as we already saw for abortion, this medical tourism will end up forcing Switzerland to give in”.

In the other camp, Recordon also considers the evolution as unavoidable. And for him the chosen strategy is the right one. “If we want to avoid the risk of the law being rejected, we have to proceed with caution, show that at least for a few years we can manage it without drifting off course, so that at least those who are afraid of excesses will be reassured. And the day when only the fundamentalist milieus are opposed to it, we can imagine going a step further,” he explains.

Since the beginning of its existence, pre-implantation genetic diagnosis has been a controversial technique, generating debate at times as heated as the debate over abortion. Its supporters consider PGD a justifiable method for avoiding the unnecessary suffering of parents who would be unable to care for a severely disabled child.

Opponents criticise the fact that not only does the test allow people to decide who has the right to be born (like abortion), but that in addition, it involves the creation of embryos which will knowingly be destroyed.

Some also fear the spread of eugenic practices, which have no medical justification. With the evolution of technology, it is conceivable that in the future embryos might be chosen based on their sex or the colour of their eyes or hair.

Debate just beginning

Doctors have been waiting for this step for a long time. “We outlined our expectations during the two consultation processes in 2009 and 2011, and it’s as if no one listened to us,” complained Dorothea Wunder, head physician in the medical reproduction unit at Lausanne University Hospital CHUV.

She welcomes the opening up that the proposed law represents, as well as the new possibility to freeze embryos, which avoids the necessity of having to start again from scratch when an implantation fails. But legally fixing the number of embryos doctors have the right to produce for each attempt (three for regular cases, eight for PGD cases) seems absurd to her.

Wunder believes the decision should be based on medical considerations and not on regulations. The PGD procedure increases the chances of carrying a pregnancy to term, which is of huge importance to couples going through torment trying to conceive.

“What affects me the most is the question of multiple pregnancies. Out of precaution we generally implant two embryos per woman, bearing in mind all the risks associated with twin pregnancies. Whereas with the possibility of freezing embryos, we could very often limit ourselves to one without reducing the chance of success. But with only eight embryos, we are not sure of finding the one that will have the best chances of making it to term.”

Dorothea Wunder and her colleagues will therefore continue to battle for a change in the law, “because if it passes in its current form, I will still advise my patients to travel abroad for the PGD. Moreover, the rate of twin pregnancies will remain unacceptably high, with consequences for increased neonatal and maternal morbidity, not to mention huge costs to the public health system.”

(Translated from French by Clare O’Dea)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.