The business of cancer research

The global cancer medicine industry is predicted to become the most lucrative therapy sector over the next few years. The industry is dominated by Swiss-based pharmaceutical giants Roche and Novartis.

Market analysts at Connecticut-based IMS Health forecasts the market for cancer products will grow to $75 billion (CHF71 billion) by 2015, an increase of about 40 per cent from the $54 billion it generated in 2009.

The ultimate goal for all actors in this profitable market is to find a cure for the disease, which the Swiss Cancer League says will affect one in three people during their lifetime. The hurdles, objectives and budgets, however, differ depending on their role in drug discovery, development or marketing.

“The challenges are the same for non-profit and profit organisations, but it’s easier to overcome hurdles if you have money,” said Beat Thürlimann, president of the non-profit Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and head of the Breast Cancer Centre at St Gallen cantonal hospital. The industry spends up to 30 times more on research than academic organisations, he noted.

Roche, which more than 50 years ago synthesised its first cancer molecule, sells the world’s top three drugs – or five of the top ten therapies, controlling about a third of the world market.

Oncology accounts for more than half of Roche’s drug sales and its research and development budget and last year the company spent 19 per cent of its sales – CHF8.5 billion – on R&D.

“With this kind of investment every year, you have to deliver drugs that make a difference, that are being used broadly and that are reimbursed by payers so they bring in revenues for future programmes,” said Stefan Frings, responsible for oncology at Roche’s partnering unit.

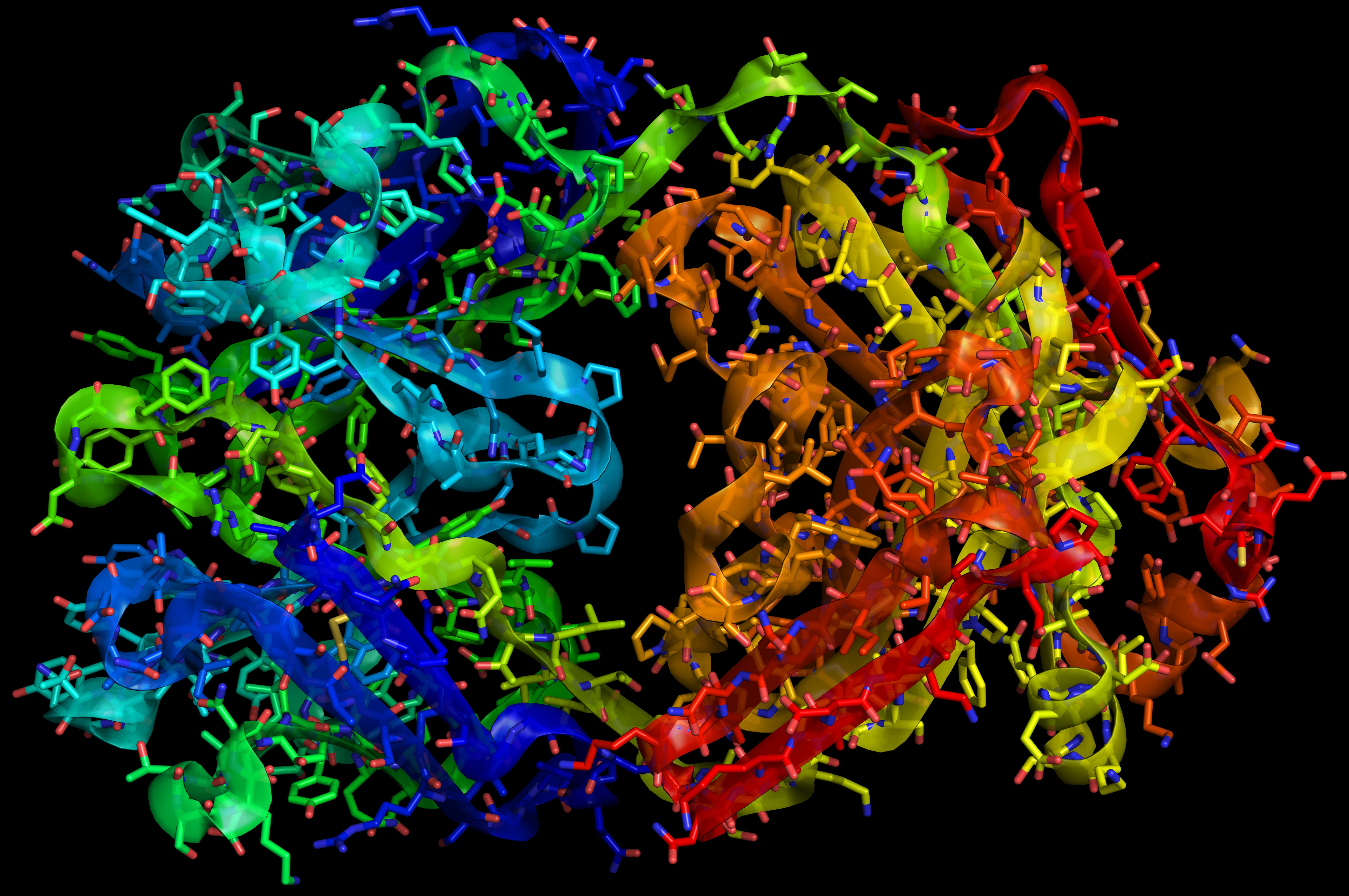

The idea behind personalised healthcare is to customise therapies tailored to the individual instead of treating patients based on symptoms – the traditional trial-and-error approach. Advances in genetic research enable a better understanding of the impact of genetics in diseases like cancer and the mechanisms that control a condition.

Cancer drugs may for example target genes, which normally control cell growth because as mutated oncogenes they promote uncontrolled cell proliferation and formation of tumours. Mutations that occur in so-called tumour suppressor genes, which control cell growth and death, may also be targeted by therapies.

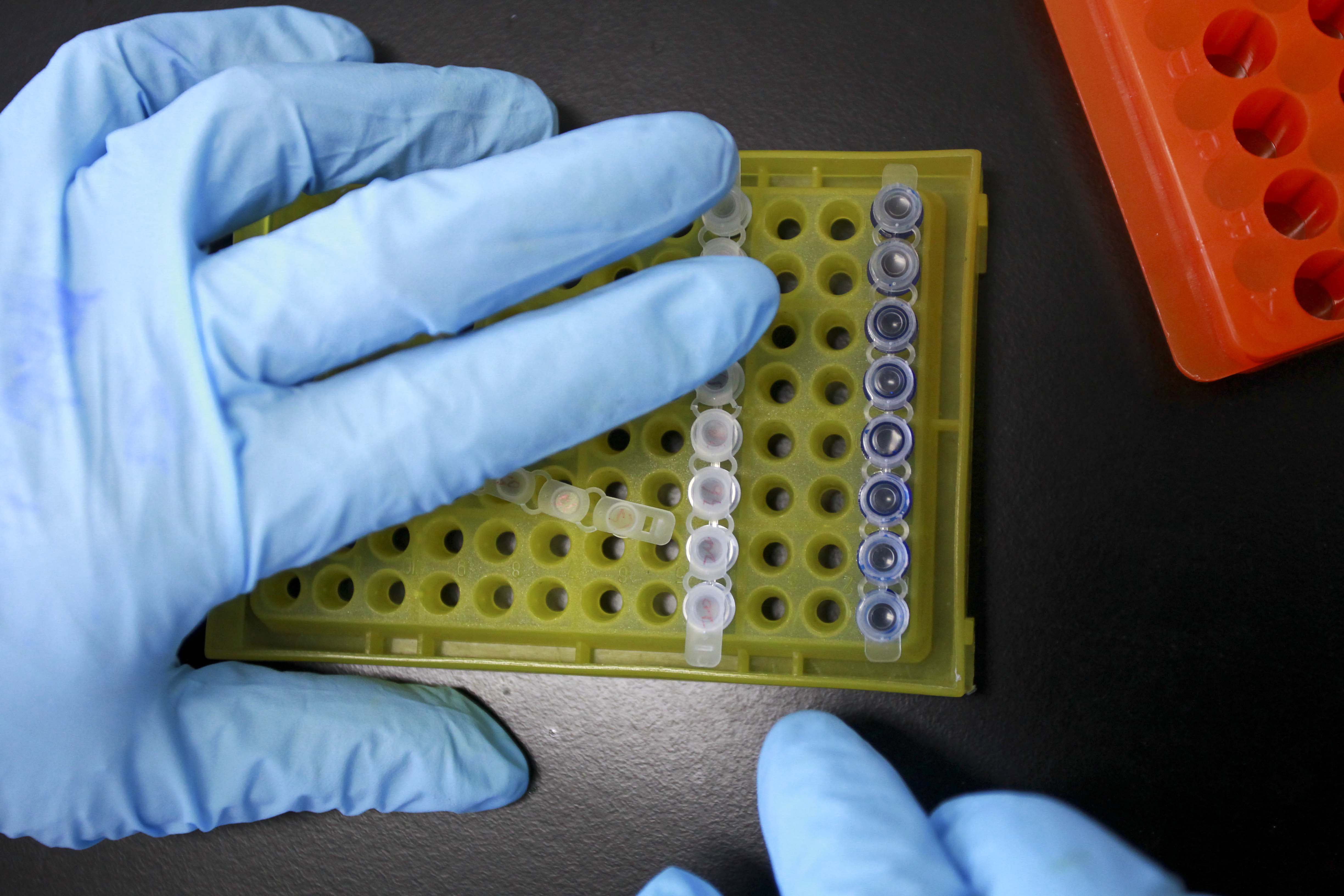

These findings allow physicians to screen patients for certain genetic mutations that play a role in tumour development. This individualisation of treatments makes drugs more effective and less harmful, but it also means that these targeted therapies only work if a patient carries a certain genetic mutation.

Magic bullets

Traditional treatments like radiotherapy and chemotherapy, which have a much broader label, account for about a quarter of the market. The dream of patients, physicians, governments, regulators and drugmakers is for more individualised treatments, which work better and with fewer side effects because they are based on the understanding of tumour biology.

Such targeted drugs, which are irreversibly reshaping the market, are more costly to develop, but at the same time they promise better therapies.

When rival Novartis’ targeted therapy Glivec, the world’s number four cancer drug, was approved in 2001, it made the cover of Time magazine, which hailed it as the magic bullet to cure cancer. Today, some of the magic has faded.

Patent losses, tougher regulatory requirements and governments’ reluctance to pay for expensive drugs are challenging drug developers. These are also the reasons why developing so-called blockbuster drugs, which generate $1 billion in annual sales, is becoming more difficult than ever before, according to IMS Health.

The way forward for drugmakers is to discover or buy patents on promising research, which may turn into innovative drugs that are first and best in class, Frings explained.

If there is no patent, there is no interest for drug developers, Thürlimann told swissinfo.ch. Research sometimes does not pay off because the product will soon lose patent protection or because the market is too small.

“If you have a rare disease caused by a rare mutation, you may not be able to run a development programme,” Frings noted.

More

Drug development’s road gets longer

Which therapy?

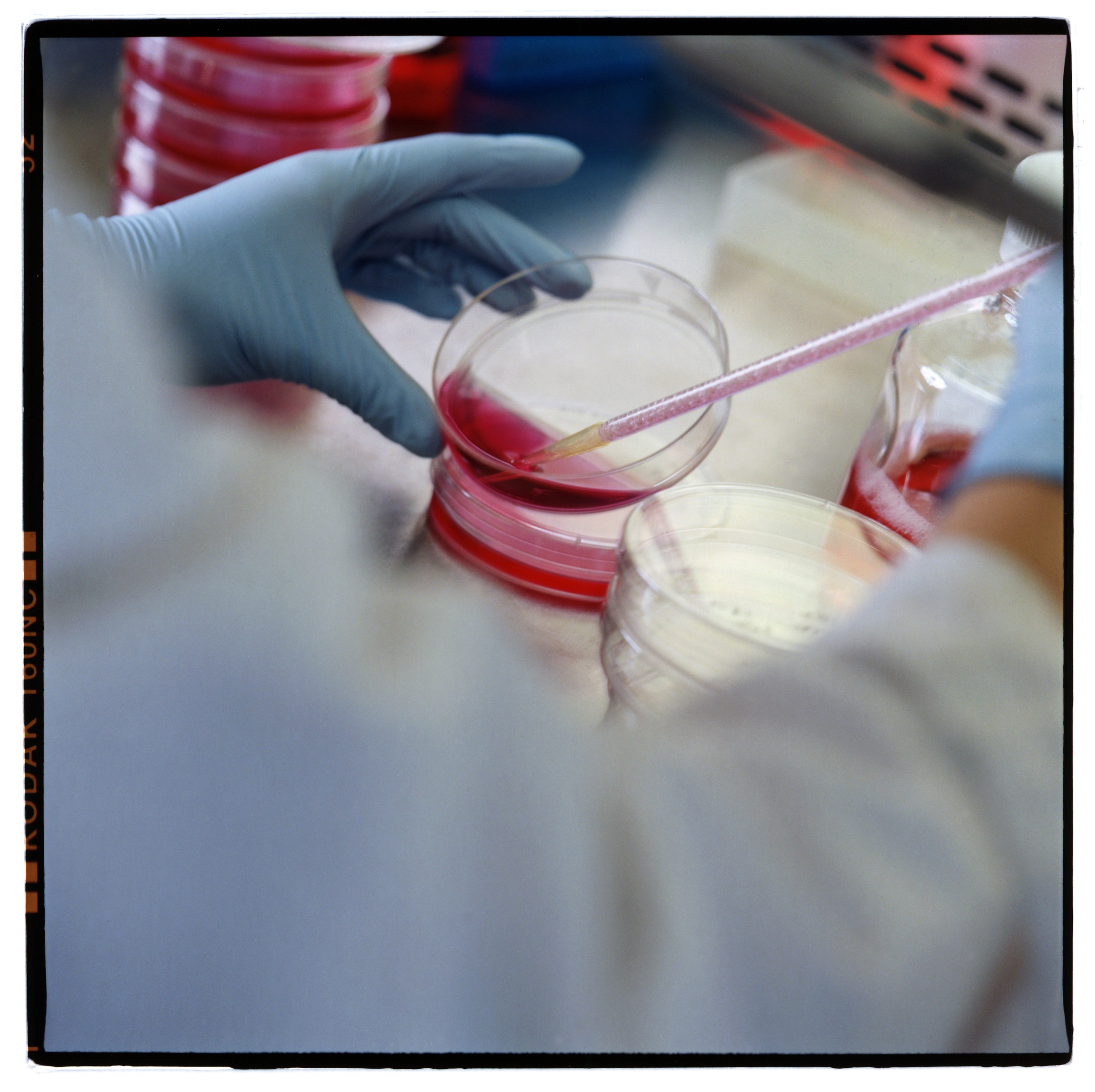

The challenge for Thürlimann’s non-profit organisation is not to discover magic bullets, but to identify the best therapy for patients by comparing what is on the market. About 40 per cent of its CHF12 million budget to conduct clinical trials comes from the government, 30 per cent each from grants and industry.

For non-profit organisations intellectual property and future revenues may be less of an issue, but at the end of the day all players not only share goals and dreams, but the nightmares too.

“The nightmare of the oncologist is that there is a drug, which is working, which is approved, which he wants to use, which he has on his shelf – and which he’s not able to use because the therapy is too expensive and not reimbursed,” Thürlimann said.

Health economics and quality of life increasingly skew decisions. With new drugs – some priced at more than $100,000 per year – doctors have to assess whether the medical benefits outweigh the drawbacks. Sometimes patients are better advised to discontinue treatment, oncologist Thürlimann said.

“With rising costs we not only ask for efficacy but for a statistically proven benefit to patients,” Thürlimann said.

“We may test whether a drug works on a lower dose or over a shorter period of time, or we look at indications, which are not a market for pharma companies.”

Evasive beast

When United States President Richard Nixon declared the “war on cancer” in 1971, many people were confident that medical researchers would tackle the disease within ten years. The endeavour, however, turned out to be far more complex.

As a research area cancer may be less fragmented and better defined than others. In Switzerland, about 40 per cent of medical research in patients is conducted in oncology, with 38 other research areas – including cardio-vascular diseases, immunology and mental disorders – making up the rest, according to Thürlimann.

But despite the fact that the human genome was fully genotyped ten years ago, cancer is still an “evasive beast”, Frings told swissinfo.ch. Many of the mechanisms driving the 250 different cancer types are still poorly understood and all require different approaches.

As cancer cells infiltrate the human body, they obtain skills – they learn to escape, mutate, divide, grow and develop resistances. Progress and inroads to understand the mechanisms and overcome all these feats typically come step by step and over decades, Frings explained.

Still, for Roche, the fact that cancer is based on definable biological mechanisms is also a blessing. It is far easier to research than poorly understood multifactorial diseases, where environment, attitudes or age may play a role, Frings said.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.