The ecologist who sniffs out plants attacked by pests

Ted Turlings's discovery of how maize plants defend themselves against insect pests was first received with scepticism. Now, more than 30 years later, he has earned a prestigious Swiss science award for his findings. SWI swissinfo.ch visited his lab to find out more about his research into farming that uses fewer pesticides.

Ted Turlings approaches the spout of a small bell jar with his nose. Inside is a maize seedling with damaged leaves and a dark-coloured caterpillar. “The smell is typical,” he says. Maize plants give off a smell of freshly cut grass and hay when they are attacked by pests.

Over the years, the ecologist has not only learned to recognise the volatiles released by their smell. He has also become one of the world’s leading experts on the interactions between plants and insects and the biological control of harmful organisms. When we meet him at his laboratory at the University of Neuchâtel in western Switzerland, Ted Turlings is checking out the scientific equipment used by his research group.

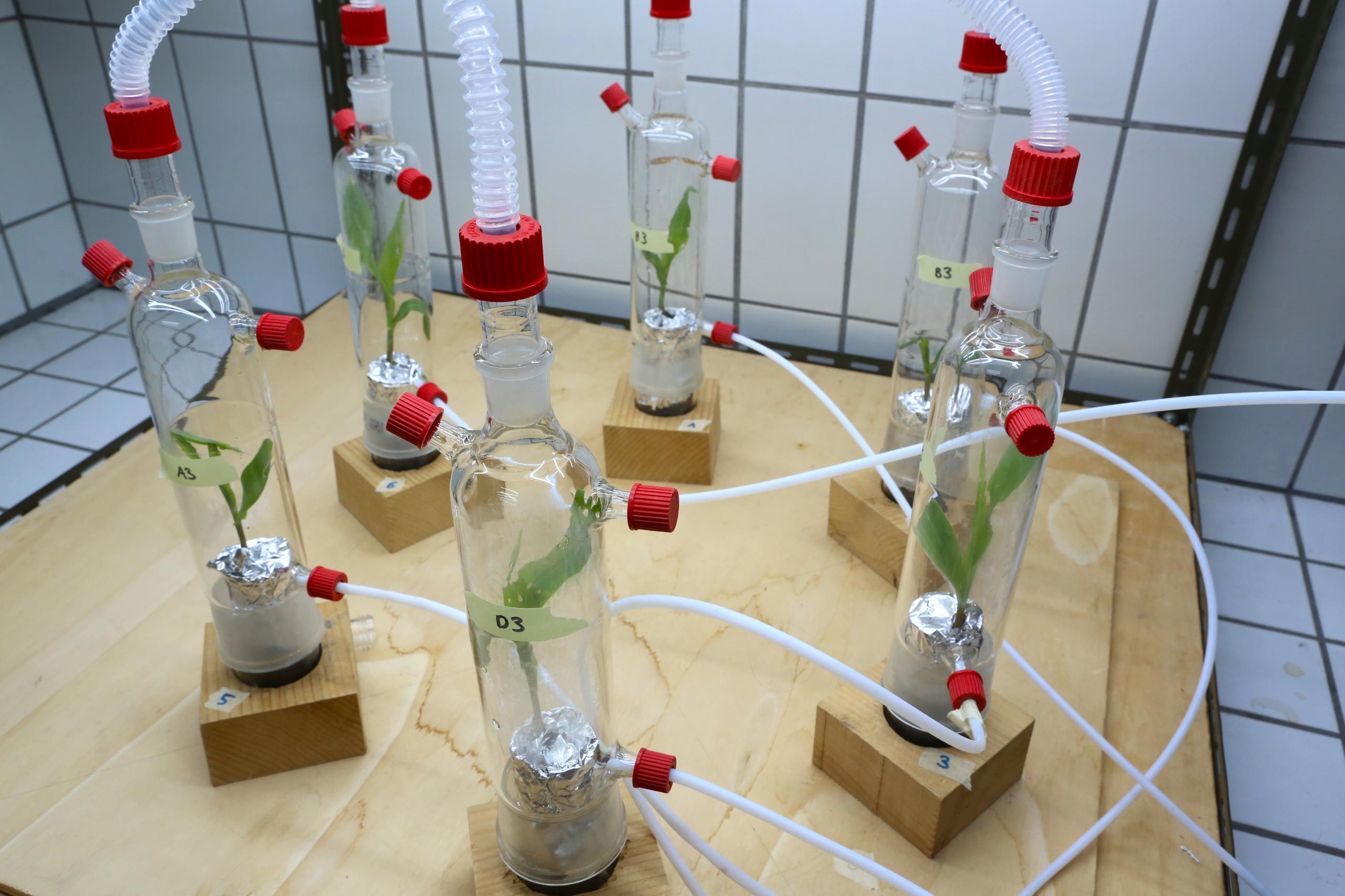

Six maize seedlings inside glass bells are connected by white Teflon tubes and a device that collects the odoriferous molecules they release. “These substances attract the caterpillar’s natural enemy. For the plant, it’s a form of defence,” explains Kathrin Altermatt, who is carrying out the lab observations together with other PhD and master’s students.

Ted Turlings was born in the Netherlands and started his research career in the United States at the University of Florida and the United States Department of Agriculture. Since 1993, he has been working in Switzerland, first at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich and since 1996 at the University of Neuchâtel. He has led the Centre of Competence in Chemical Ecology at the University of Neuchâtel since 2014. In 2023, he was appointed president of the International Society of Chemical Ecology.

At 64, their professor is approaching the official retirement age. But Ted Turlings has no intention of stopping. He is preparing for a new phase in his career. He wants to finally put his research into the defence mechanism of maize plants into practice and develop effective and cheap solutions against insect pests, which still destroy up to 40% of crops worldwideExternal link.

“I said to myself long ago that research should not only lead to scientific publications but also help find solutions to important problems.” he says.

When the enemy’s enemy comes to help

Ted Turlings is currently working on an odor sensor that can detect the volatile molecules produced by caterpillar-infested maize plants in real time. These molecules attract parasitic wasps that lay eggs inside the caterpillar’s body. When they grow, the wasp larvae devour the caterpillar from the inside, killing it. “The plant defends itself by calling an enemy of its enemy to the rescue,” Turlings says.

His idea is to install the sensor on farm machinery or a robot that moves through crop fields to alert farm managers to what is happening to their crops before pest damage becomes visible.

His prototype sensor is still too bulky and expensive – at least CHF300,000 ($351,000) – for large-scale deployment in developing countries. A company in Zug, central Switzerland, is already working on a smaller, cheaper model.

The sensor-equipped robot would be able to identify the infested area of the crop, so only that area would need to be sprayed with pesticides. Synthetic products in particular are harmful to the natural environment and the people who handle them, and yet their use has almost doubled worldwide since the 1990sExternal link. To help reduce the use of pesticides, Turlings wants to bring in another natural enemy of the caterpillar.

A worm gel against the caterpillar

Nematodes are microscopic worms that usually live in the soil. They can be part of the maize’s defence arsenal and are attracted to substances released by the roots. Like wasps, nematodes can attack and kill caterpillars that feed on leaves. Ted Turling’s team has developed a gel that contains these nematodes and can be applied where the caterpillar begins to devour the maize plant.

In Europe, the United States or Asia, the gel could theoretically be applied directly by the robot that has “smelled” the presence of a pest. In Africa, where agricultural cooperatives are unlikely to be able to afford robots, the gel could be applied by hand using large “syringes.” Experiments in RwandaExternal link have shown that this method of biological control can be as effective as pesticides, according to Turlings.

The gel could help control the fall armyworms, a species of moth native to South and North America. Since the pest was first detected on the African continent in 2016, it has entirely colonised the sub-Saharan region, infesting nearly every field and causing billions of dollars in damageExternal link.

“It can migrate over very long distances and, favoured by global warming, is also very likely to arrive in Europe”, Turlings says. He believes that the fall armyworm could arrive in Switzerland in two to three years.

Discovery, scepticism – and recognition

Born in the Netherlands, Ted Turlings has always been passionate about nature. In his spare time, he loved birdwatching, while in the laboratory he focused on plants and insects.

During his biology studies, his professors introduced him to biological control. This approach uses antagonistic relationships between organisms to manage populations of species that are harmful to plants and humans.

At the age of 25, Ted Turlings moved to Florida to work at the US Department of Agriculture. During his doctoral research, he made the most significant discovery of his career while investigating how parasitic wasps locate maize plants infested by caterpillars.

What attracts the wasp is neither the odor of the caterpillar nor that of its droppings, as previously thought, but the odor that the plant gives off when it senses a substance contained in the caterpillar’s saliva. It was an intriguing discovery, Turlings recalls, because it suggested that the plant is able to recognise the organism that is devouring it.

The young researcher was the first to establish the exact chemical identity of the volatiles emitted by maize plants and later was involved in the identification of the key compound in the caterpillar saliva, which was named volicitin. The discovery was publishedExternal link in the journal Science in 1990, but was initially met with scepticism by some fellow scientists who were studying the interactions between plants and insects.

Richard Karban, an entomologist at the University of California, remembers well the reactions of other researchers in the field. He was not surprised by the scepticism towards Ted Turling’s new findings. “In general scientists are conservative when it comes to new ideas that challenge their long-held beliefs,” he wrote in an email to SWI swissinfo.ch.

OExternal linkther External linkresearch groupsExternal link then obtained similar results in their lab experiments over the following years. For Ted Turlings, the satisfaction was great. Researchers later also discovered that the volatiles are also detected by neighbouring plants, which then prepare themselves for the caterpillar’s attack.

“Turling’s research has informed what we know about how plants defend themselves against herbivorous insects and how we might use those defenses to increase crop production,” Richard Karban points out.

Ted Turlings had to wait 30 years to be fully recognised, at least in Switzerland where he has been working since: In October 2023, the Marcel Benoist Foundation awarded him the eponymous prizeExternal link, given annually to resident researchers whose work has made a major contribution to the benefit of human life.

The so-called Swiss “Nobel Prize” for science was awarded to Ted Turlings because his research on biological pest control “shed light on complex biological phenomena” and had a “worldwide impact in the field of environmental science”, the foundation writes.

This prize spurs Turlings on even more. “My work is not yet finished,” he says.

Edited by Sabrina Weiss/vm

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.