Who wants to pay to fight malaria?

Tremendous progress has been made in the fight against malaria in the past decade mainly thanks to private donors. But the battle is far from over as states struggle to agree on a binding global treaty to fund so-called neglected diseases.

“While the anti-malarial market is huge in terms of those in need, it is small in terms of profit.” This statement by the non-profit group Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) in one of its promotional brochures may seem brutal.

But it clearly shows why malaria, formerly known as marsh fever due to its associations with swamps and originating from mala aria, meaning bad air in Italian, continues to kill 781,000 people a year, mostly young children and pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa.

In recent years the parasite which causes malaria has developed a growing resistance to classic drugs and the pipeline for new products has dried up.

A group of public and private donors, including the Swiss government, therefore decided to found MMV, which helps develop and deliver new, effective and affordable anti-malarials. In 2003 a similar organisation emerged – the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), co-founded by Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and aimed at developing new treatments.

Backed by private money from donors such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, they have largely contributed to helping reduce the number of malaria cases over the past ten years.

“In the previous two decades it was all bad news. After dreams of eradicating malaria in the 1960s, the situation got worse. The fight was taken up again in the 2000s with new resources and treatments and a widespread use of impregnated mosquito nets which helped reduce the number of cases in certain countries,” explained DNDi director Bernard Pécoul.

But malaria remains a “neglected disease” affecting mainly poor countries.

“If you look at all new medicines discovered over the past 30 years, only one per cent was linked to neglected diseases which are nonetheless responsible for over 12 per cent of all deaths worldwide,” said Pécoul.

Success story

MMV, DNDi and partners are working to correct this imbalance. One example is the Novartis drug Coartem, considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be the best anti-malarial on the market.

In the 1990s Coartem was developed for Western travellers going to tropical regions and cost $12 (SFr11.74) a treatment. But this was far too expensive and not properly adapted for African children. In 2003 Novartis approached MMV to partly finance a development programme for the drug.

Since 2001, following an agreement with WHO, Coartem has been sold at cost price – $1 a treatment – and has already changed the lives of around one million children. Novartis earns nothing in financial terms but a great deal in terms of image.

Unfortunately, this success story is rather “exceptional”, said Pécoul.

Long overdue treaty

In order to change things, organisations fighting malaria and other neglected diseases hope WHO will adopt a binding research and development convention that focuses on the health needs of developing countries.

The subject was on the agenda of the last WHO General Assembly held in May in Geneva. A WHO expert group has recommended that every country contributes 0.01 per cent of their gross domestic product to this effort, which would raise the funding level for research into illnesses affecting the poor from $3 billion to $6 billion.

But this move is unacceptable for most Western countries, led by the United States, Japan and most European countries.

After discussions which MSF described as “extremely tough”, Western nations managed to delay plenary talks on the issue for a year following regional consultations.

“We supported Kenya’s proposal to open negotiations immediately,” said Katy Athersuch, who took part in the talks for MSF. “We now hope this extra year will not be another lost year and that states will use it constructively.”

Swiss position

Switzerland also rejected the idea of a binding convention, but had a more nuanced position.

“We realised that we wouldn’t get consensus,” said Gaudenz Silberschmidt, head of international affairs at the Federal Health Office. “The expert group handed in its report one month before the General Assembly meeting. I don’t know a single country that was able to consult all ministries concerned and come up with a consolidated position in such a short time – especially for financial issues.”

The expert group’s analysis was excellent, said Silberschmidt.

“But we are not convinced that a convention is the solution. We are going to urgently look closely at this question to see what would be the best adapted institutional mechanism,” he added.

According to the Swiss Malaria Group, Switzerland has given SFr51.1 million to the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria, but remains one of the least generous European nations in financial terms.

Almost half the world’s population is exposed to malaria, which kills nearly one million people a year, mostly young children under the age of five and pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa.

The economic impact of the disease is immense, causing lost days of work and loss of tourism and investment.

There are four main types of malaria, all spread by mosquitoes.

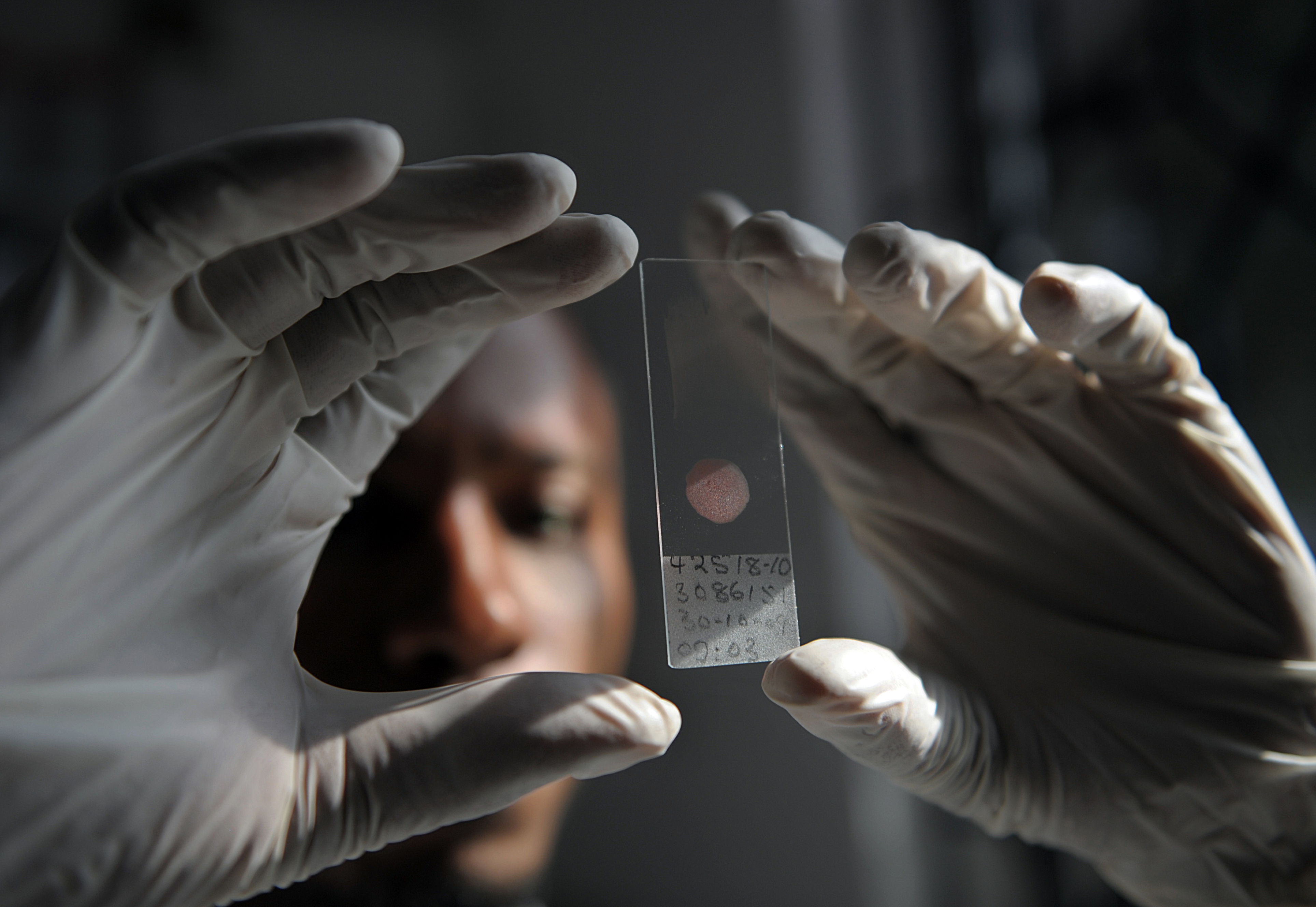

Malaria is caused by a parasite of the Plasmodium species and is transmitted by the bite of a female Anopheles mosquito.

Many drugs have lost their effectiveness against the parasite as it adapts. There is no vaccine but advanced testing is underway of one that could offer partial protection.

Insecticide-treated bed nets and indoor spraying of houses with insecticides are two methods of keeping the Anopheles mosquito at bay.

Currently, the most effective drugs are combination treatments containing artemisinin – derived from a plant that has been used for centuries in traditional Chinese medicine to treat fever.

Malaria has been largely beaten in the richer parts of the world, with 108 countries free from the disease, but tackling the disease in poor and tropical countries is more difficult.

RTS,S, (Mosquirix) developed by GlaxoSmithKline, is one of 20 promising malaria vaccines under development but for which tests are the most advanced. Some 16,000 children aged 5-17 months from seven African countries have taken part in phase three clinical trials.

The preliminary results show a 50 per cent reduction in the risk of catching malaria. RTS,S may be available in two years’ time and sold at cost price – less than $2 a dose.

(Translated from French by Simon Bradley)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.