Swiss gravity battery contributes to China’s energy transition

Sun and wind produce electricity even when we don’t need it. How can we prevent it from being lost? A gravity battery developed in Switzerland stores renewable energy in heavy blocks of material – an idea that is attracting interest around the world, especially in China.

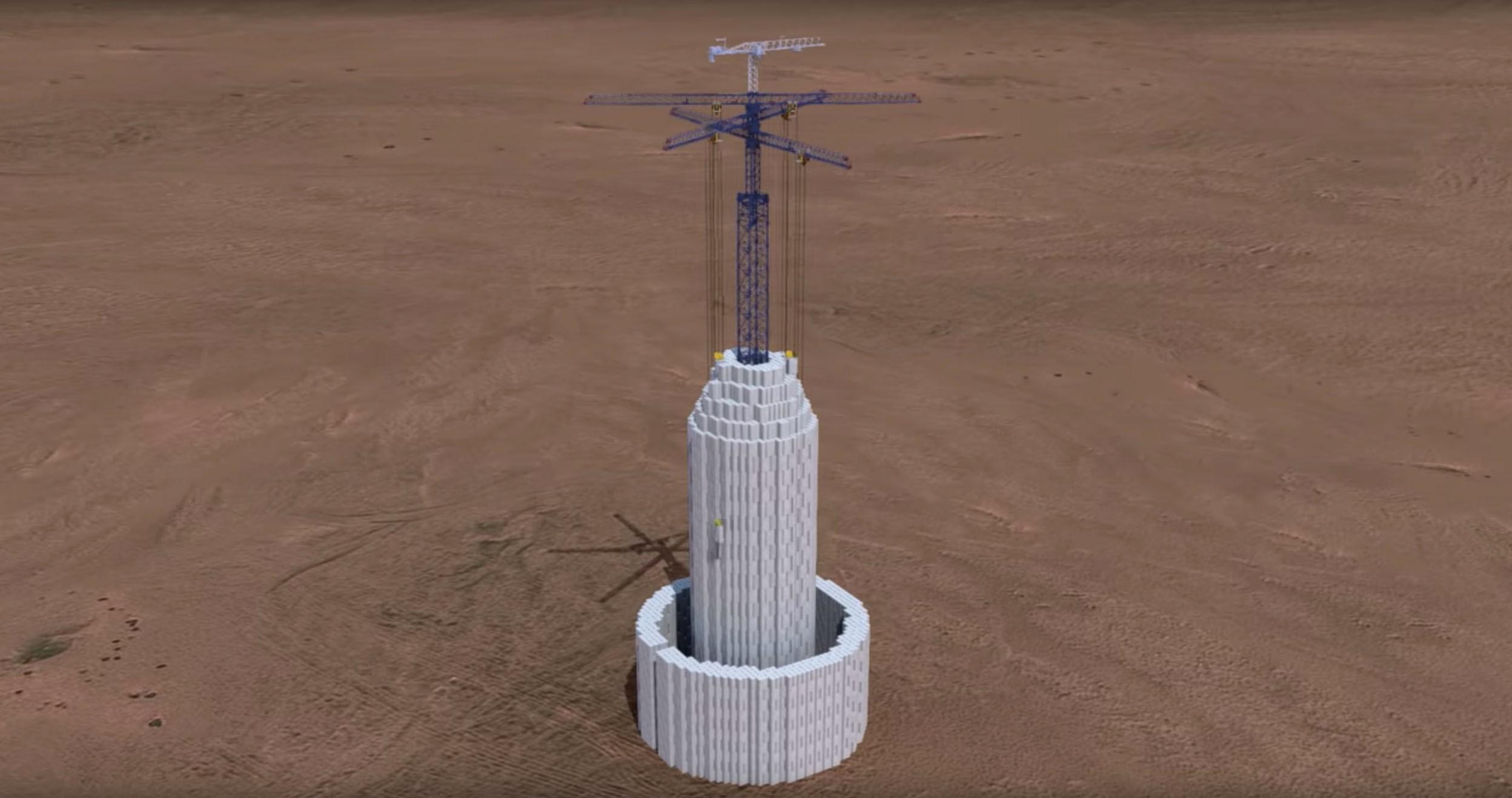

It is an imposing building without doors or windows. Inside there are 3,500 “bricks” weighing 25 tonnes. A system of elevators and tracks moves them up and down, placing them next to each other, in what looks like a modern 3D Tetris. It is not a new housing concept, but a battery that uses the force of gravity to store and release energy.

The first battery with this technology was connected to the power grid in the Chinese county of Rudong, near Shanghai, in late 2023. “We didn’t imagine that our first plant would be built in China,” Robert Piconi, CEO of Energy Vault, tells SWI swissinfo.ch. The energy storage systems company is based in the US, but it developed and tested its prototype in Switzerland.

More

Newsletters

In China the environmental imperative to accelerate the country’s decarbonisation – China is the world’s biggest emitter – and current energy policiesExternal link have, however, offered unexpected opportunities for Energy Vault and its innovation. New battery-buildings are already under construction. “We want to help solve the climate crisis,” Piconi says.

Energy storage systems are an essential part of the energy transitionExternal link. Batteries solve one of the main problems of electricity production from renewable sources: volatility. That is, they allow excess electricity generated by the sun or wind to be stored and made available at times of increased demand. They can also help stabilise electrical grids. The challenge is to produce efficient batteries without consuming raw materials and rare metals. And of course, at sustainable costs.

More

Swiss solutions for storing the energy of tomorrow

Weights instead of water

Gravity batteries can store large amounts of energy. They do not deteriorate, and the storage capacity does not decrease over time, as is the case with the electrochemical batteries used, for example, in our smartphones.

Gravity batteries are based on the same principle as hydroelectric power plants with a pumped storage system. These account for over 94% of the world’s installed energy storage capacity, according to the International Association of Hydropower.

More

Inside Switzerland’s giant water battery

However, the Energy Vault battery does not work with water, but with weights. In this case, blocks of concrete or waste material.

When the sun or wind produces more electricity than required, as in summer, the excess energy feeds a system that lifts the weights and places them on the upper floors of the battery-building. This process converts electrical energy into potential energy.

When the electricity is needed, the blocks descend to the ground or to a lower level at a controlled speed. During the “fall” they drive electric generators, transforming the stored potential energy into electric current. The computer software developed by Energy Vault, the heart of the innovation, optimises the mechanical process of lifting and lowering the blocks according to the electricity demand.

Energy Vault’s first commercial battery in China stands next to a wind farm. It has a storage capacity of 100 megawatt hours (MWh). Once “charged”, it could power around 4,600 electric cars travelling 100 kilometres.

>> Watch the short animation on how the Energy Vault gravity battery works:

‘Revolutionary technology’ for China

The Rudong battery is part of the “new energy storage demonstration pilot projects” defined by China’s National Energy Administration, according to Energy Vault.

The plant was built in cooperation with the American Atlas Renewable and China Tianying, one of the leading companies in waste incineration for electricity production. The company uses waste materials and coal ash to make some of the battery blocks. It has invested $100 million (CHF91 million) in Energy Vault.

Yan Shengjun, president of China Tianying, claims that Energy Vault’s “revolutionary technology” will facilitate the shift from fossil fuels to solar and wind power and accelerate China’s energy transition. Chinese decision-makers appreciate the possibility of using local raw materials to build the facility and its lifespan of more than 35 years, according to an article in ForbesExternal link.

Three such batteries are under construction in China and six more are in the planning stage. Together they will have a storage capacity of 3,700 MWh.

Larger installations will reduce costs, says Robert Piconi. The cost of future installations will be at least 30% lower than that of the first battery in Rudong (about $500 per kilowatt-hour of installed storage capacity), he says.

More

Next-gen batteries: Swiss researchers help lead the charge

Reliability still to be verified

Wenxuan Tong, a researcher at the Smart Grid Research Institute in Beijing, believes that gravitational energy storage technology will play a “critical role” in achieving national climate goals. China wants to reach peak emissions in 2030 and climate neutrality in 2060.

The Energy Vault battery could be realised almost anywhere. It does not depend on specific geographic or climatic conditions. An energy efficiency similar to that of pumped storage hydroelectric power plants (80-85%) and the simplicity of its equipment make it “cost-effective”, Wenxuan Tong tells SWI swissinfo.ch.

However, he points out that the economic effectiveness of a large-scale plant and its compatibility with China’s existing power grid are still to be verified. “More research and practice are needed to verify its efficiency and reliability,” he says.

Gravity batteries for medium- and long-term storage

Energy Vault is not the only company using gravity to store and release energy. Other concepts use inclined planes or underground installations. The Canadian company Gravitricity, for example, is building the world’s first underground gravity energy storage prototype in a disused mine in Finland.

The main advantage of gravitational batteries is the low energy storage costs, according to Julian Hunt, a researcher at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Laxenburg, Austria. The disadvantage, however, is the relatively high cost of the electricity needed to move a weight from one level to another.

“Thus it only makes sense to apply gravity storage for weekly, monthly or seasonal storage cycles,” Hunt writes in an email to SWI swissinfo.ch. For storage of less than 12 hours, electrochemical batteries are a more practical and cheaper alternative.

The Energy Vault battery in China operates on a four-hour cycle. This is a feature required by the authorities and the electricity grid operator. The system could also release energy for a longer period, but in this case the power output would be lower.

A solution also for Europe?

Robert Piconi agrees that gravitational batteries are better suited for longer charge and discharge times. However, the demand for long-term energy storage is still small. “It will increase when there are more renewable energy plants connected to the grid,” he predicts.

The CEO of Energy Vault is not only looking at China. Energy storage projects are already underway in the US, southern Africa and Australia.

The gravitational battery could also be a solution in some European countries, Piconi believes. For example, in nations that are building new wind farms or large solar power plants, such as Spain or Italy. Or in those that are leaving the coal era behind and could use the waste (ash) to make blocks of material to be lifted. “I’m thinking of Germany and Eastern European states,” he says.

There appears to be ample opportunity, provided the local populations do not reject battery buildings on aesthetic grounds, as is often the case with planned wind and solar farms.

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.