Is psychedelic therapy about to go mainstream?

Geneva is home to the only Swiss hospital offering psychedelic-assisted therapy. Despite the hype, full legalisation of the treatment still has a long way to go.

A Netflix documentary spurred François, a 52-year-old policeman and father of four, to try psychedelic therapy. Along with another volunteer, a 70-year-old woman, he drank a few micrograms of psychedelic drug LSD.

The patients of Professor Daniele Zullino, the head of psychedelic-assisted therapy at Geneva University Hospital (HUG), don’t fit the typical stereotypes association with drug-taking. Most of them had never seen psychedelics before being presented with a capsule of psilocybin – a substance derived from mushrooms – or a vial of LSD at the doctor’s office. For a price of CHF199 to CHF445 ($221 to $494), depending on dosage, volunteers embark on a “trip” lasting up to 12 hours. François’ goal: to cure his decades-long depression.

And while health insurance doesn’t cover the cost of such drugs, the potential benefits makes them worth the price, François says. “If I never need to buy antidepressants again, the maths is easy.” François has had three psychedelic experiences in the past year. So far, the results have been impressive. “All the symptoms of depression have gone,” he says. “I have a new taste for life.”

Want to read our weekly top stories? Subscribe here.

As of 2024, psychedelics are legal or have been decriminalised in 23 countries. Switzerland has a long history with such drugs, ever since LSD was discovered in Basel in 1938. Together with the US, Canada and Australia, the country leads the way globally on psychedelic therapy and research. And since 2014, Swiss patients have been able to access psychedelics for compassionate use in last-resort cases. Yet so far, the HUG is the only place in the country offering safe psychedelic treatment in a big medical environment.

“Patients come from all over Switzerland to get treated here,” says Zullino. If research is one of the goals of offering the treatment, therapy is the main objective. “We are the first in the world to propose a legal treatment with psychedelics outside research protocols,” he tells SWI swissinfo.ch. Since 2019, Zullino and his team have treated 200 patients – a record in the field.

Success stories

Zullino has often seen success stories like François in patients for whom traditional therapy was not helpful. “Mental diseases are due to a rigidity in neuronal connexions, making it difficult for those affected to change their view of life,” Zullino explains. “If you’re depressed, you can’t see the positive side of things.”

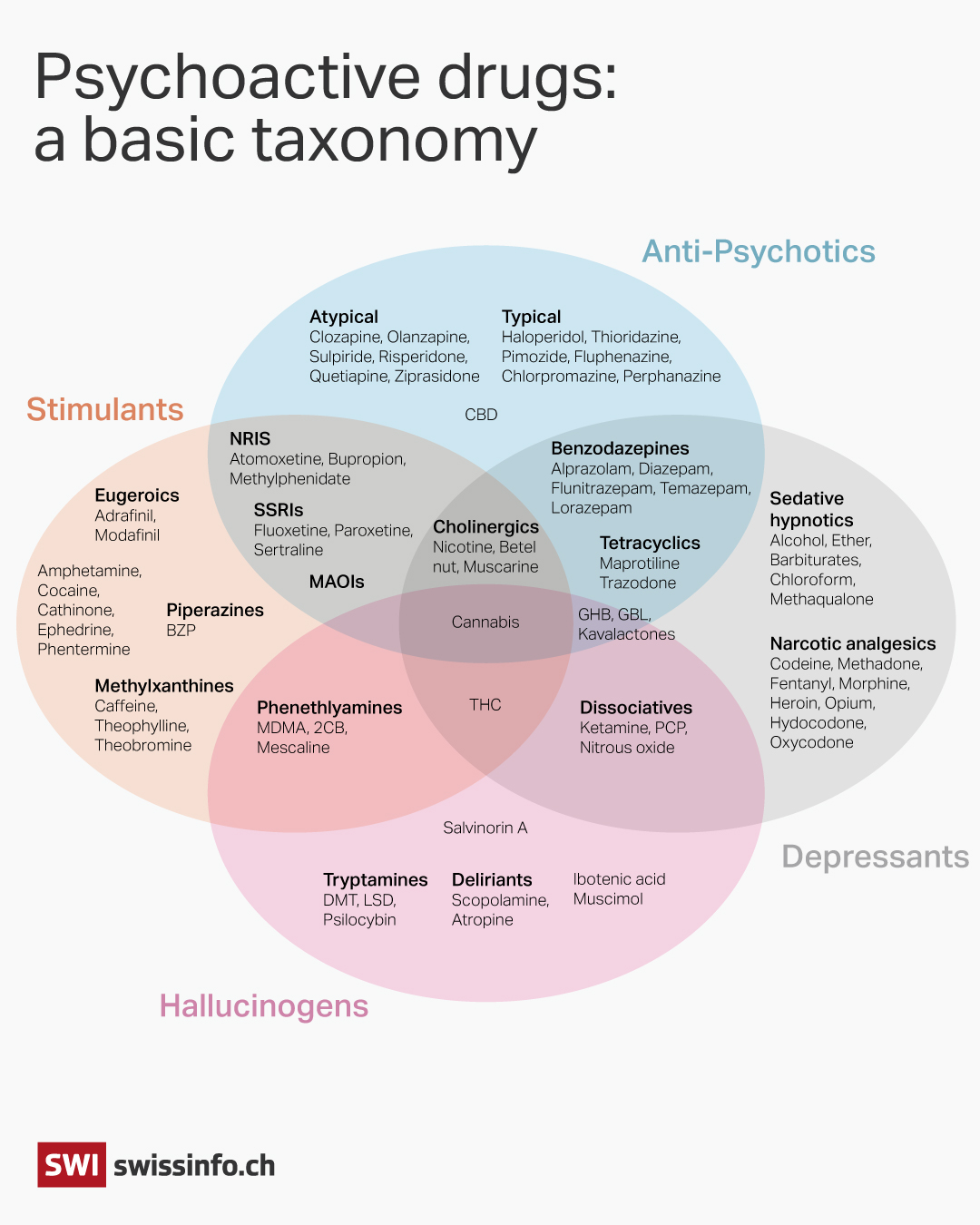

Psychedelics, a sub-group of psychoactive drugs, can alter mood, cognition, and perceptions. In doing so, they build new connections within the brain. LSD and psilocybin – the options proposed by the HUG – are the best-known forms. Other psychedelics include DMT, mescaline, MDMA and ketamine. These substances are all used in clinical trials in Switzerland and worldwide.

But the drugs alone don’t explain the mental breakthrough which many patients experience.

“Psychedelics prepare the ground for the new beliefs and ideas explored in therapy to take hold,” says Zullino. This is why, at the HUG, the hours spent under the drug’s influence are framed with psychotherapy sessions – to “set the intention for the trip” and to “integrate the experience”. This psychological support is critical to the healing process.

Expert disagreement

In the world of psychiatry, where there have been no breakthrough drug discoveries since anti-depressants in the 1950s, psychedelics have caused a shockwave. With little to no risk of addiction and minimal side effects, psychedelics seem to be more effective than many psychiatric drugs currently on the market – at least when administered in the right setting.

This element is key for Laura Tocmacov, co-founder of Psychédelos, a patient association in Geneva. “Around one-third of patients who come to the association after undergoing psychedelic-assisted therapy have either experienced no therapeutic effect or even fresh trauma,” she says.

For former patient Tocmacov, this is not due to the drugs as such, but to the conditions in which they were taken. “Some patients were left alone during bad trips, which caused a lot of anxiety,” she says. “Others were treated by an unqualified therapist who didn’t manage to create a reassuring atmosphere.”

The question of the right environment for a psychedelic experience divides specialists. For Tocmacov, all therapists should themselves try psychedelics before administering them. For Zullino, this is not necessary. “Does a gynaecologist need to be a woman?” he asks.

Tocmacov also insists that newly-trained “psychedelic” therapists should learn from the experience of shamans or underground healers. “Their traditions tell us that the psychedelic experience is enhanced when it happens in natural or spiritual settings,” she notes. “On the other hand, a white room in a clinic can create anxiety in some patients.”

On the contrary, Zullino believes spiritual elements don’t add anything. “We try to use neutral rooms where patients can project their visions, rather than imposing our visions on them,” he says.

Scientific research on the subject is still in its infancy. Stringent protocols frame most studies on psychedelics done to date, dictating every interaction between doctor, patient and the surrounding environment. This framework is meant to allow scientists to compare the drug’s effect to that of a placebo, rather than evaluate its impact in different settings.

HUG doctors are not bound by these research protocols, as their research focuses on how to optimise the therapy which frames the use of psychedelics, rather than on the pharmacology of the drugs. “We can test new music, ask patients different questions, change the drug’s environment or dosage, and explore what works best,” says Zullino. The knowledge compiled by he and his team could serve as a basis for training standards in Switzerland, for new therapists open to offering psychedelic treatment to their patients.

Road to legalisation

Adult Swiss residents who want to try psychedelic-assisted therapy currently need to prove several things to the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH): that they suffer from a treatment-resistant disorder; that they have tried several medicines and therapies without seeing improvement; and that their disease is significant and durable, and leads to anxiety, depression or addiction.

The limited scope of who qualifies for the therapy has meanwhile enabled an uncontrolled world of underground options to flourish. If caught, illegal psychedelic users generally don’t risk much more than a fine.

Maxime Mellina works for the Groupement Romand d’Etudes des Addictions, a citizen association in the French-speaking part of Switzerland which deals with addictions and related public policies. He argues that “by allowing the substance only in strict medical settings, we exclude all those who don’t have a serious mental illness, but would still like to try psychedelics for personal growth, pushing them to turn to illegal, uncontrolled offers”.

Meanwhile there have been significant global movements calling for a change in the regulatory status of psychedelics.

And such debates could soon result in the medical benefits of psychedelics gaining recognition in Switzerland. From being used only as an exception in last-resort cases, the drugs could evolve to be used more generally in treatments, thereby creating the need for more experienced therapists. “This change should start happening within two years,” reckons Zullino.

Mellina believes there is no reason to ban psychedelics at all. “They don’t represent any risk of addiction and don’t lead to problematic behaviours like alcohol does, for example,” he says. The question is rather how they should be liberalised: “should they be available to everyone, like a glass of wine? Or just in a pharmacy?” he asks.

Zullino is a strong advocate for regulating psychedelics as medicines. As for other uses, he insists this is an entirely different issue. The confusion between medicines and drugs “discredits the efforts of scientists to ensure better access to much-needed treatment”, he says. But the distinction between medical use and the rest might not be easy to make. “Where does therapy start and end?” asks Mellina. “When I have a glass of wine after work, is this recreational or therapy?”

This year may yet mark a turning point for the legislation around psychedelics worldwide, as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has agreed to review MDMA-assisted therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. If it approves the therapy, this could significantly influence the regulatory process in other countries, and may lead to expedited or facilitated reviews. In Switzerland, where Albert Hofmann first synthesised LSD in 1938, psychedelics could be widely available within five years, says Mellina.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/dos

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.