Turning Swiss CO2 into Icelandic rock

Efforts to capture carbon dioxide (CO2) from dirty industries and store it deep underground are generating huge interest globally. Switzerland is also examining what to do about its hard-to-tackle CO2 emissions. A Swiss pilot project in Iceland shows great promise, say researchers. But is this costly and complicated method worth the effort?

Check out our selection of newsletters. Subscribe here.

Imagine capturing CO2 from industry before it enters our atmosphere and turning it into stone – forever. Swiss scientists have been exploring this idea in a pilot project as part of ongoing carbon capture and storage (CCS) plans. These involve technologies that remove CO2 from industrial processes, such as sewage treatment or steelmaking plants, and store it deep underground to help meet the country’s goal to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

The captured CO2 is not stored in Switzerland, but in Icelandic geological reservoirs. The team behind the pilot project recently announced that the approach is technically feasible and has garnered massive interest, proudly declares coordinator Marco Mazzotti, a professor of mechanical and process engineering at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich.

“The amounts of CO2 that we store are irrelevant for the climate. But the fact that we’ve done it and that we had to solve all these practical problems and bring together a large consortium has generated huge momentum,” he tells SWI swissinfo.ch. By this he means the 23 universities, research institutes and companies that are involved.

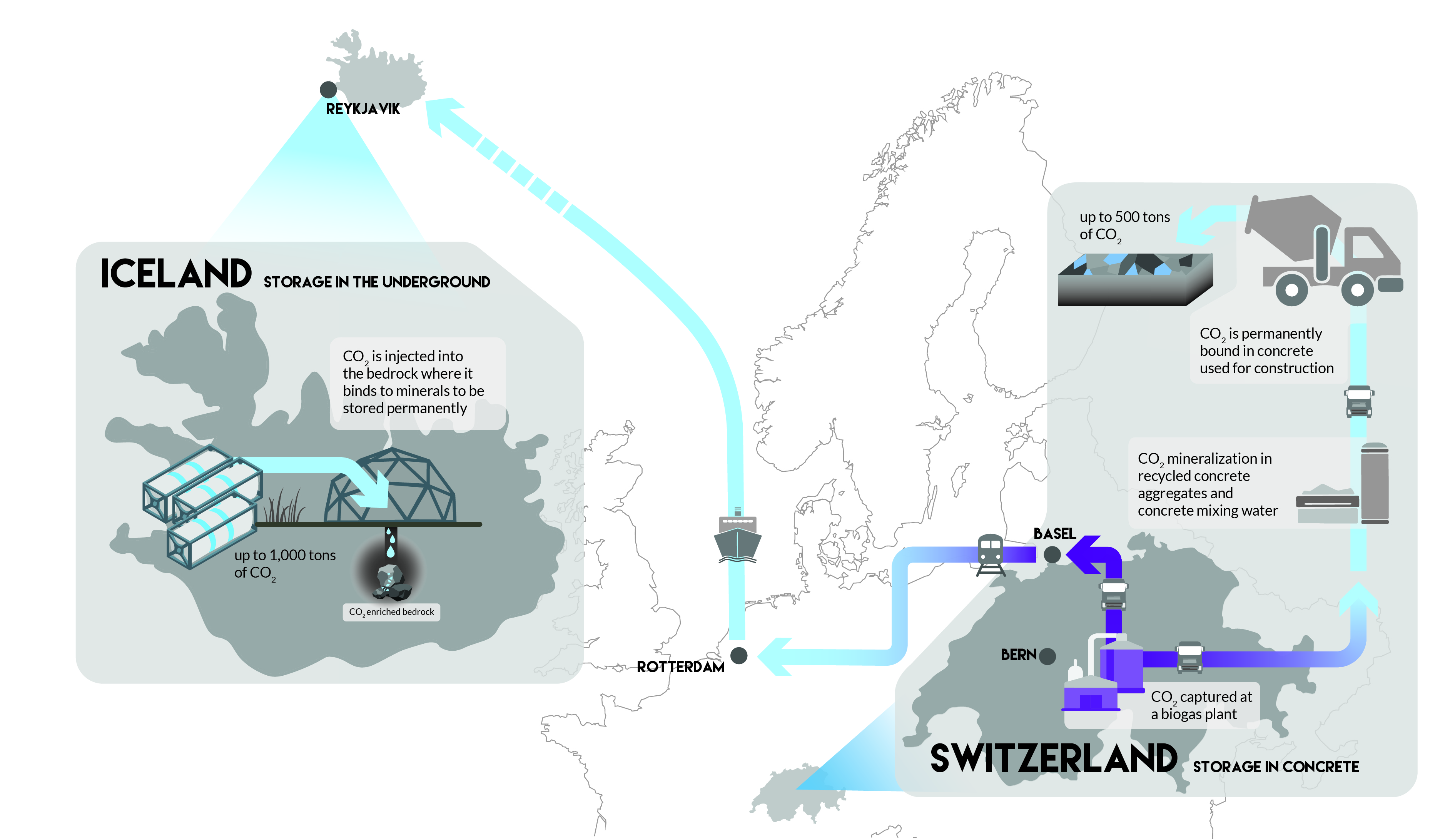

In the ongoing trials of the DemoUpCARMAExternal link project, CO2 is captured and liquefied at Bern’s main waste treatment plant. From there, it is taken by truck in a 20-tonne container to Germany, then by train to the Netherlands and onwards by sea to Iceland. From the capital Reykjavik, the container is driven to a site in the west of the island. Each 2,400-kilometre truck-train-ship-truck journey takes roughly five weeks. Such a long, complicated journey and process generates additional emissions, but the project team has done its calculations and is convinced that implementing such an approach on a larger scale would pay off.

So far, around 100 tonnes of Swiss CO2 have been sent to Iceland, which is considered ideal for underground storage due to its many basalt rock formations. Basalt is a dark-grey, porous rock formed from the cooling of lava which contains high amounts of calcium, magnesium and iron.

Fizzy CO2, seawater and basalt

At the coastal site of Helguvík, the Swiss CO2 is first mixed with seawater from a nearby well. The fizzy liquid is then pumped by a local company 300-400 metres underground, where it binds with the basalt and is expected to form limestone within a few years. In this solid form, the CO2 is permanently stored. More deliveries and injection tests will continue until autumn 2024 to complete the project, alongside more scientific monitoring.

Long seen as a technically complicated and expensive solution with marginal utility, CCS is now deemed necessary by both the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Energy Agency (IEA) to balance out any greenhouse gas emissions that are unavoidable. Over 390 CCS projects are operational or in development around the world, according to the Global CCS InstituteExternal link.

Besides the massive use of renewables and energy-saving measures, the Swiss government saysExternal link 12 million tonnes of hard-to-tackle CO2 emissions from waste plants, agriculture and sectors like the cement industry must be cut to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Thanks to CCS, around 500,000 tonnes of CO2 could be permanently stored by 2030, and up to seven million tonnes by 2050.

Yet CCS projects have drawn criticism from some environmental groups, partly because of the high costs and infrastructure needs. WWF has warnedExternal link that CCS “remains unproven at scale and is not a silver bullet” to address industrial emissions in Europe.

Nathan Solothurnmann, an energy and climate expert at Greenpeace Switzerland, says Switzerland should first prevent CO2 emissions before developing such mega-projects. It could do so by improving waste recycling methods, replacing conventional concrete with other building materials, and reducing livestock.

“These measures will help to eliminate a considerable proportion of ‘unavoidable’ climate emissions,” he tells SWI swissinfo.ch.

Infrastructure and transport challenges for CO2 storage

The Swiss team behind the Iceland project is certain of its green credentials. While additional CO2 emissions are generated along the supply chain when CO2 is transported to Iceland, they say the process still removes far more CO2 from the atmosphere than it emits. In all, the Swiss team calculated that for every 100 kilograms of stored CO2, 20 kilograms of CO2 are emitted due to trucks, trains, ships and other processes.

The capture, transport and storage of carbon dioxide using the DemoUpCarma model reportedly costs around CHF300 ($328) per tonne. Costs could be brought down in the future via a more efficient integrated storage system, an established regulatory framework and more experience in transport management.

One of the biggest headaches for Mazzotti’s team has been ironing out regulatory and legal issues. One issue is that many interested stakeholders are watching and waiting to see how the CCS technologies, regulations and market evolve before investing.

The Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN), which is co-financing the project in Iceland, has also acknowledged this. “Emitters only want to capture CO2 once the transport infrastructure is there. But the transport and storage structure will only be developed when there are customers who want to capture and sell their CO2,” Sophie Wenger, a project manager at FOEN toldExternal link Swiss public radio, SRF.

CCS has gained an early foothold in North America. In Europe, ideas about the future capture, storage, transportation and use of CO2 are evolving rapidly. Several projects in the North Sea region want to show that cross-border solutions are feasible. These include the Greensand projectExternal link inaugurated last year, where CO2 from Belgium is being injected into depleted oil fields under the Danish North Sea.

The European Union recently published its Industrial Carbon Management StrategyExternal link and a studyExternal link on the development of CO2 infrastructure and pipelines in Europe that would replace trucks and trains. Switzerland is not included in the plans, which Mazzotti was disappointed to learn.

“It’s really sad to see that the pipelines just go around Switzerland because we don’t have any collaboration on these things at the right level. We can’t do these things alone. The Swiss need to do them together with Europe,” he says.

Storing CO2 under Switzerland?

The Swiss authorities are also pursuing local CCS plans, albeit more slowly. They have earmarked a borehole in northern Switzerland no longer required by the National Cooperative for the Disposal of Radioactive Waste (NAGRA) as a possible test injection site. The first trials could begin in 2030. But overall, the potential to store CO2 in Switzerland is low. A national underground exploration scheme is investigating further, but the Federal Office of Energy admitsExternal link storage sites would not be operational for 15-20 years.

In an initial phase until 2030, the Swiss authorities plan to promote CO2 storage options abroad. At the regulatory level, the government has been laying the groundwork. After the 2009 amendment to the London Protocol, since January Switzerland can export CO₂ for storage in sub-seabed geological formations. The Alpine nation has signed deals to develop carbon storage technologies in Sweden, the Netherlands and Iceland, and discussions are ongoing with Norway.

Technologies are needed to capture or remove CO2 and store it permanently. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) captures and stores fossil and process-based CO2 at installations like waste treatment plants to cut emissions, while negative emission technologies (NETs) focus on permanently removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

NETs include, among others: afforestation and reforestation; land management to increase and fix carbon in soils via additives like biochar; bioenergy production with carbon capture and storage (BECCS); enhanced weathering; direct capture of CO2 from ambient air with CO2 storage (DACCS), ocean fertilisation to increase CO2.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement will require a very rapid global expansion of CCS and NETs, in addition to a substantial reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

“Companies in Switzerland are now free to utilise this option as part of private-sector agreements with foreign providers of CO2 storage, such as in the North Sea,” said FOEN spokesperson Robin Poëll via e-mail.

Projects subsidised by the Swiss Climate Cent Foundation, an association set up by businesses to compensate CO2 emissions, could take advantage. So could the waste treatment industry, which has committed to CO2 capture by 2030 under an industry deal with the federal governmentExternal link. Swiss firms in the EU emissions trading system, such as cement producers, would also be able to take credit for CO2 capture and storage in the seabed from 2025.

Nathan Solothurnmann urges the Swiss authorities to be cautious. Rushing into CCS technologies would lead to a lock-in effect, he warns.

There would be no incentive to seriously reduce emissions and examine natural alternatives to capturing and storing CO2, he says.

“Large investments would be made in CO2 infrastructure and there would be no turning back.”

More

Newsletters

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.