How a Swiss-US study challenges what we know about the Gulf Stream system

A system of Atlantic Ocean currents vital to regulating the European climate has not shown any sign of decline in the last 60 years, according to a new study from Swiss and US scientists. But it doesn’t mean that concerns over the collapse of the Gulf Stream are unfounded.

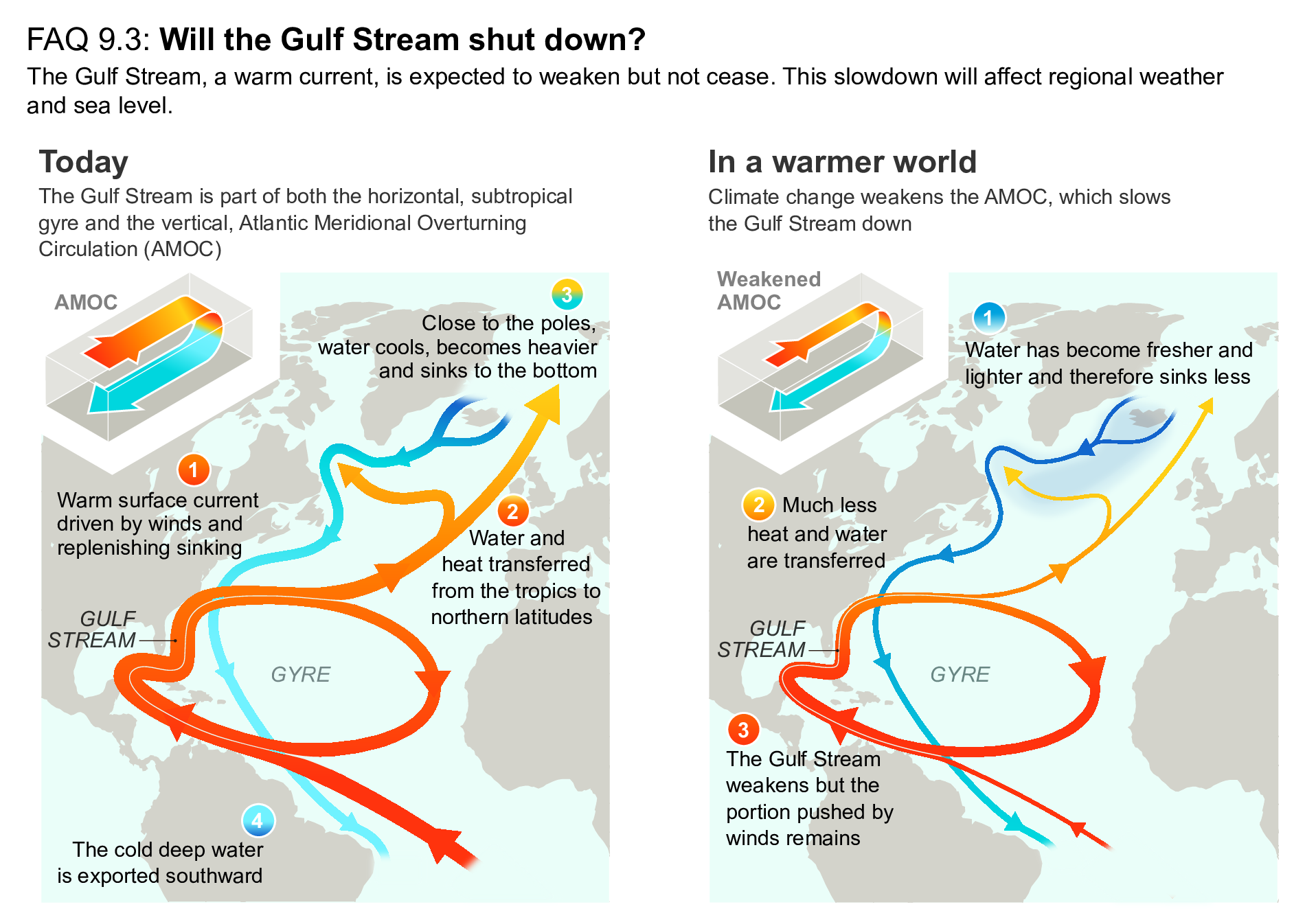

The study looked at the “conveyor belt” system of currents known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). The Gulf Stream is part of the AMOC, and both are in an interconnected system that brings vast amounts of water from the tropics to northern regions. The findings offer fresh insights into an alarming – and uncertain – field of climate research.

Europe owes its mild climate largely to currents in the Atlantic. The flow of warm water from near the Equator to Europe keeps cities like London several degrees warmer than places at similar latitudes on the Pacific coast of Canada. The AMOC also distributes oxygen and nutrients in the ocean.

‘No clear trend’ in AMOC weakening, says new study

In recent years, the impact of our warming planet on the Gulf Stream system has given rise to numerous scientific publications warning of its weakening – or even possible collapse. Now, new research published in Nature CommunicationsExternal link by scientists from the University of Bern and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the US concludes that the current has been stable over the past 60 years.

Using a novel method involving 24 Earth system models and observation-based estimates of heat flow between the ocean and atmosphere in the North Atlantic, they found that no slowdown was detectable in the AMOC between 1963 and 2017.

“Our reconstructions show considerable variability, but no clear trend can be identified,” says lead author Jens Terhaar from the University of Bern

But this does not mean that the AMOC will not decline or collapse in the future.

The AMOC will undoubtedly be weakened by climate change very soon or maybe even started weakening in the years after 2017 when the Swiss team’s reconstructions end, Terhaar acknowledges. But since the current has been stable up to 2017, an entire collapse is less likely in the near future, he adds.

“The AMOC will decline substantially, that’s virtually certain and the consequences will be extremely grave,” Terhaar says. “However, it remains uncertain how great this weakening will be and when a collapse will happen.”

New ‘robust’ methodology

A major problem for scientists studying AMOC is that they lack direct evidence. Precise measurements using instruments submerged in the middle of the ocean date back only to 2004. So researchers traditionally rely on a combination of inputs – rising ocean surface temperatures, declining salinity, and satellite images – to build models of the AMOC.

In its work, the Swiss-US team questioned the use of sea surface temperatures as a proxy for the strength of the AMOC. As some other studies have already shown, surface temperature anomalies in the North Atlantic are not only influenced by the AMOC, but also by other processes in the ocean and atmosphere.

“You really need a strong AMOC decline to robustly see that in sea surface temperatures. Otherwise, there are too many other processes that influence sea surface temperatures in addition to the AMOC,” says Terhaar.

Changes in the heat flow between the ocean and the atmosphere are a much more effective indicator, as “that’s where the main change happens,” he adds. Although this heat flow is a better indicator, estimates of the heat flow are more uncertain than sea surface temperature measurements, so large uncertainties remain.

More

Predicting the climate of the future with 1.2 million-year-old ice

While the researchers claim their new reconstructions are more reliable than previous ones, they come with “limitations and caveats”. These include uncertainties inherent in observation-based estimates. Processes like ice melt from Greenland may not also be calculated in the models.

‘Greatly underestimated risk’

Terhaar says the publication has received “positive, challenging and constructive” reactions from peers so far.

Pascale Lherminier, an oceanography researcher at Ifremer [French Institute for Ocean Science and Technology] who was not involved in the study, said the methodology was extremely solid.

“Linking heat fluxes at the air-sea interface with AMOC makes much more sense than linking ocean surface temperature with AMOC,” she told the AFP news agency.

Warnings about a possible future collapse of the current caused by global warming are not new.External link Recent alarming studies that point to a weakening of the Gulf Stream system and tipping point estimates as early as 2025-2095External link have made headlines but are also contestedExternal link within the scientific community.

In October, around 40 top scientists warned in an open letterExternal link of the “greatly underestimated risk” of a “major change” to AMOC. A weakening of the current could have “devastating and irreversible impacts” for the climate and biodiversity.

These would badly affect Nordic countries, the scientists wrote, due to major cooling and unprecedented extreme weather. But there would be consequences for other regions, such as a shift in tropical rainfall belts, reduced ability of the ocean to absorb CO2 and rising sea levels, particularly along the American Atlantic coast.

In its most recent assessment in 2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which effectively sets the scientific climate consensus, concluded that AMOC would not collapse this century.

“The AMOC will very likely weaken over the 21st century (high confidence), although a collapse is very unlikely (medium confidence). Nevertheless, a substantial weakening of the AMOC remains a physically plausible scenario,” it said in its sixth assessment reportExternal link.

Edited by Veronica De Vore/gb

More

Newsletters

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.