Removing Russia from CERN ‘helps Putin’, scientists fear

Russia has contributed significantly to scientific research at Geneva-based CERN. The recent decision to halt this collaboration helps Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine and sets a dangerous precedent, according to Russian and European scientists contacted by SWI swissinfo.ch.

“There are so many conflicts in the world. If scientific cooperation is restricted, there will be consequences for CERN’s future projects and cooperation,” says German physicist Hannes Jung, who argues that Russia’s ouster from the organisation opens the door for similar treatment of other countries.

In December 2023, the Council of CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, decided to end cooperation with Russia and Belarus in responseExternal link to the “continuing illegal military invasion of Ukraine”. The Russian Foreign Ministry reacted to the decision in March, calling it “politicised, discriminatory and unacceptable”.

More

Newsletters

The decision is unprecedented. In the past, CERN sanctioned Yugoslavia by suspending cooperationExternal link during the Bosnian war in 1992. But before ceasing cooperation with Russia and Belarus, it had never excluded countries from international scientific research. The scientific relationship between CERN and Russia had existed for almost sixty yearsExternal link.

The organisation based on the Franco-Swiss border near Geneva signed the first agreements with Soviet laboratories in the 1960s, at the height of the Cold War. In 1991, the Russian Federation was granted observer status at CERN. Since then, Russia has made significant contributions, both financially and scientifically, to the experiments conducted at the nuclear research institute.

More

Former CERN head has served science and peace for 100 years

Consequences for research

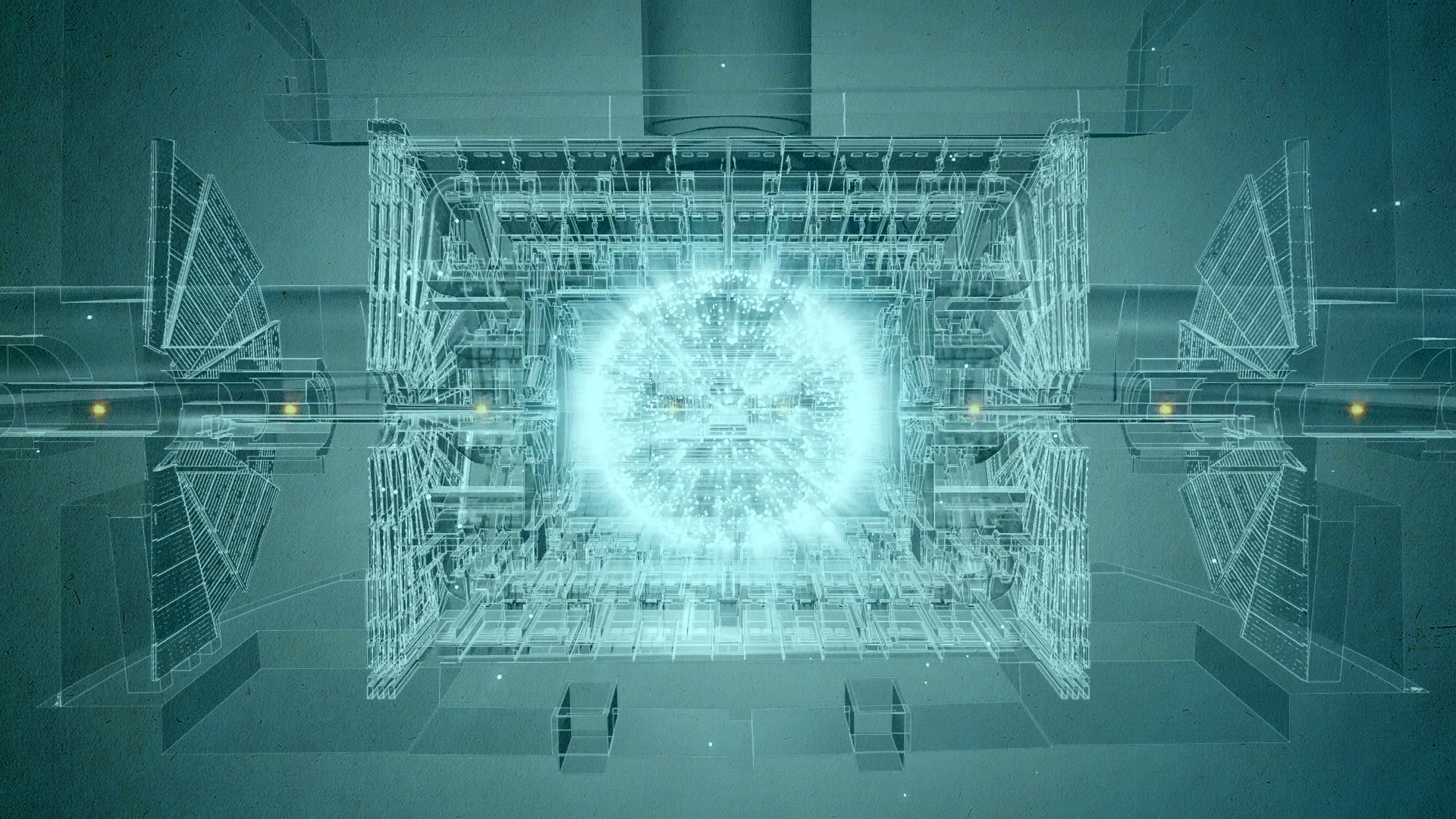

Among the consequences of this decision is the loss of more than CHF2 million ($2.2 million) per year, which Russia had paid to CERN through 2022 and part of 2023, according to CERN. Russia’s contribution helped finance the construction of CERN’s Large Hadron Collider particle accelerator (LHC), the world’s largest and most powerful machine for the study of particle physics. SWI swissinfo.ch estimates, and CERN confirms, that Russia has financed at least 4.5% of the approximately CHF1.5 billion of total costs for LHC experiments over the past 30 years.

In its medium-term planExternal link for 2024-2028, CERN has also indicated that it will have to raise an additional CHF40 million to make up for the lost Russian contributions to the particle accelerator upgrade project, the high-luminosity LHC. On top of the financial losses will come the loss of Russian personnel and know-how in the various experiments being conducted at CERN. All this will have an impact on its operations, the document says.

More

What CERN’s next-generation particle collider could look like

Hannes Jung is a physicist emeritus at the Desy Institute in Hamburg who has worked with CERN for years. He sees other risks besides CERN’s funding gap in Russia’s exit from the organisation. Now, Jung believes, the Russian scientists excluded from CERN could be driven to instead contribute to Russian military research out of necessity. And the money Russia would have paid to CERN will likely help fuel the war against Ukraine.

“Instead, it would be important and positive if Russia continued to spend financial and intellectual resources to support experiments and research at CERN,” Jung says. “Otherwise we don’t help Ukraine.”

Jung and many other scientists are concerned about the future of the Geneva-based organisation, which was set up to bring people from different countries together and build bridges through science.

Jung, now retired, came to CERN in the 1980s as a student from West Germany. Right from the start he was fascinated by the atmosphere of exchange and dialogue among people from countries divided between the Eastern and Western blocs of the Cold War era. Jung recalls that part of CERN’s detector technology was built by casting brass shell casings from the Russian navy.

“We were turning weapons into instruments of peace. Now this will no longer exist,” he says.

Consequences for Russian and Belarusian scientists

The CERN resolutionExternal link will take effect from June 27 for Belarus and from November 30 for Russia. In the coming months, hundreds of scientists affiliated with Russian and Belarussian institutes collaborating with CERN will cease their research work within the framework of the Geneva organisation’s experiments. According to CERN, about 500 people are affected.

“It’s a sad situation,” says one of the affected scientists, Fedor Ratnikov. “It’s frightening from the outside as well as from the inside. In my opinion one should not break ties with good people,” he says. The 61-year-old Ratnikov is a chief scientist affiliated with the Russian government-funded Higher School of Economics (HSE University) in Moscow and has been working on experiments at CERN for almost two decades. He does not see many prospects for his future at CERN.

“I will most likely retire if I’m pushed to do military research in Russia,” he says, while expressing hopes that a way can still be found to collaborate with CERN.

Many of his colleagues with what he calls “key” functions for CERN have already moved to Western institutes to continue international cooperation. But for Ratnikov, this is not an option. Having returned to Russia in 2016 after several years in the United States, the scientist believes he can be more useful in his country. “I came back to Russia to advance research projects in my country. Besides, my mother needs my attention,” he says.

Politics prevails over science

CERN declined to make any comment on its council’s decision to cease cooperation with Russia and Belarus. “We cannot comment on a decision that belongs to our member states and with which CERN must comply,” said Arnaud Marsollier, media spokesperson for the research organisation.

CERN is indeed bound by the resolutions voted on by its council, which consists of two delegates – one with a more political role and one with a more scientific one – for each of the 23 member states. Member States contribute more than observer countries (as Russia was) to CERN’s budget. Switzerland, for example, contributes around CHF40 millionExternal link annually, while Germany makes the largest contribution with CHF220 million per year.

Although the CERN Council represents the political interests of its member states, until now it had succeeded in guiding the organisation exclusively according to its scientific interests, keeping political tension out of the picture, states former CERN employee Maurizio Bona. “CERN was established to work on science and promote intercultural dialogue and peace, there was no political pressure,” he says. “But in 2022, politics has suddenly prevailed over the interests and principles of science.”

“For four decades CERN was my home. I was convinced that the orientation of the organisation had never been imposed by political pressure and we scientists prided ourselves on this. I was really disappointed,” he says.

Listen to the episode of our podcast ‘The Swiss Connection’ on CERN’s plans for its next-generation particle collider on Apple Podcast or SpotifyExternal link.

Putin’s dream scenario

Russian physicist Andrei Rostovtsev, a member of Science4PeaceExternal link and former CERN collaborator, is among those who believe the decision to oust Russia and Belarus from scientific collaboration was purely political. “Scientific progress has been sold to politics,” he says.

Sources close to CERN and its scientific community told SWI swissinfo.ch that on December 15 the delegations of most member states voted following direct instruction from their respective governments. In February, the online news site The Geneva ObserverExternal link revealed the details of the secret vote: 17 of the 23 member countries of the CERN Council voted against the continuation of the cooperation agreements. Hungary, Israel, Italy, Serbia, Slovakia and Switzerland abstained.

Contacted by SWI swissinfo.ch, the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation did not comment on the reasons for this abstention, citing the confidentiality of the discussions.

Rostovtsev argues that it was easy to cut Russia out of CERN, since it had already contributed to the construction of the particle accelerator and detectors. Other international science projects, such as France’s IterExternal link, are still heavily dependent on Russia and therefore could not afford to oust it, he says.

The scientist, who runs dissernet.org, a website against plagiarism in Russian science, is sure that Russia’s ouster from CERN will help Russian president Putin. “[He] will use it as an argument to convince the Russian people that the countries around him are enemies,” says Rostovtsev. This allows him not to have to decide to cut science funding himself in favour of funding the war.

“They have realised a dream of Putin’s,” he says.

Edited by Veronica De Vore/ds

More

Diplomatic isolation of Russia – a tricky strategy in International Geneva

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.