Seed Warriors target global hunger

As food riots return to Africa, a Swiss documentary asks how the world will be fed in just a few decades when global warming causes major losses in food production.

Mirjam von Arx, co-director of Seed Warriors, tells swissinfo.ch about the challenges and possible solutions, focusing on the Svalbard Global Seed Vault near the North Pole and the agricultural situation in Kenya.

The film starts with a Pythonesque sequence of three women scientists dancing – pole dancing? – in the snow in full lab gear.

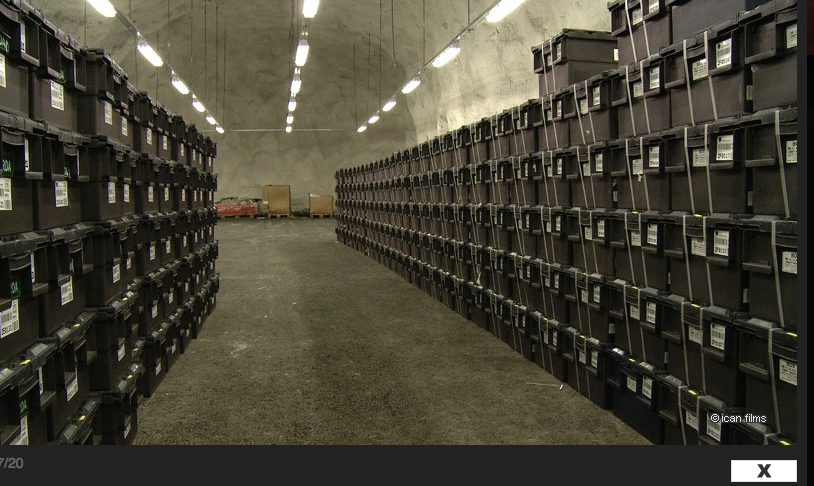

Having grabbed the viewer’s attention, the rest of the English-language documentary switches between the so-called Doomsday Vault – a sort of apocalyptic garden centre – and the arid fields of Kenya.

Agricultural scientists and climatologists discuss the vault’s contribution to the fight against hunger as well as the plant breeding that needs to be done in the countries themselves to prevent mass starvation.

Seed Warriors has just been released in Swiss cinemas and will be released on DVD on December 9.

It is thought-provoking and avoids the shockumentary, statistics-heavy approach of many eco-docs. But don’t bother with popcorn: shots of tearful African farmers holding withered ears of corn puts things into harsh perspective.

swissinfo.ch: How did you get the idea for the film?

Mirjam von Arx: Katharina von Flotow [writer and co-director] stumbled on it when she was making a documentary on Darwin. When it was announced that a seed vault would be built in Svalbard, there was a lot of discussion among scientists whether it was a Utopian dream or complete nonsense – a solution or just a whitewash for politicians who want to be seen to be presenting a solution.

I come from a completely different field, but I thought it was very interesting because if it was possible with such a global problem for nations to come together and cooperate – not only on an international basis but also across scientific disciplines – then we might be able to solve some other problems too.

swissinfo.ch: So the seed warriors are scientists?

M. v A.: Yes. Originally the title was The Seed War, but then we thought actually it’s more about the people, the scientists. There are lots of other seed warriors around the world, in NGOs and so on. In my eyes you’d be a seed warrior if you planted something on your balcony…

But when you consider how many people are starving, it is a war. And when you then think what’s going to happen in ten, 20 years when climate change is really going to start hitting and there’s a shortage of water and fertiliser, I don’t even want to think what’s going to happen.

swissinfo.ch: You’re a seed worrier…

M. v A.: This issue is a time bomb. Sometimes you think “God, can this even be solved?” If the scientists and politicians can’t get it together, then I don’t see how we can win.

Ultimately, if the food crisis hits countries that are unstable to begin with, it will affect all of us – not just because they’ll want to come to Switzerland or wherever, but because the economy is global. As long as we want to work globally, we should be really concerned.

swissinfo.ch: The world can live without polar bears but not without food – why doesn’t this issue get more attention?

M. v A.: If you show a cuddly animal, everyone goes “poor animal”! If you show a plant that’s drying up, it doesn’t have the same emotional effect. That’s part of the problem.

But also politicians are concerned with short-term solutions – they want to get elected in a couple of years. Very few will work towards a solution that will come into fruition when they’re long gone.

swissinfo.ch: There’s a conspiracy theory that Bill Gates is planning on filling the vault and then destroying the rest of the world’s seeds like some James Bond villain…

M. v A.: I’m always amazed at the theories that people come up with. It’s true that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has put in a lot of money, but it also funds in situ preservation. It contributed to the seed vault, but so did companies like Monsanto and Syngenta who don’t store their seeds there [no genetically modified (GM) seeds are stored in Svalbard]. I can’t see why that is so bad – they should give something back. I think they absolutely should give money.

swissinfo.ch: Isn’t Seed Warriors two separate documentaries fused together?

M. v A.: I don’t think so, because if you don’t see the struggles facing a gene bank in say Africa, you won’t understand why Svalbard is needed. To me it was very important to juxtapose the reality and why you need this bloody great vault.

The vault is basically a giant bank deposit box, so the national gene banks need to know what they send. Ideally it would be characterised, so you know that this crop has these genes which might be good in crossing for heat tolerance or whatever. If the owners of the seeds don’t do that, it’s not going to happen. So a lot of the responsibility is still with them and we need to understand that.

It’s an important first step and especially for a lot of Asian and African seed banks it’s extremely important to have this back-up. But ultimately this is not going to feed us – there’s a lot more that needs to be done and it needs to be done in the countries where the crops are coming from. They need to be enabled and that involves finances.

swissinfo.ch: How do you balance informing the audience and shocking them?

M. v A.: I think you can justify both approaches, but what we wanted to do was show solutions. So we have all these scientists explaining what could and should be done – it’s definitely not “we’re all doomed”.

The problem is time and money: if we don’t do it now, in 20-30 years it’ll be too late. Financially it’s almost ridiculous how little money you would need to get going, but it’s just incredibly difficult, from what we’re told, to raise it and to get governments to give money.

I’m cautiously optimistic. I’m not so sure we can trust in humans to do the right thing, but I think there is a possible solution. If we’re doomed, it’s because we’re too stupid – not because it can’t be done.

Food shortages are already a problem. Last week, Mozambique’s government said it was reversing bread and water price increases that had touched off riots that killed a reported 13 people.

Olivier De Schutter, the UN special investigator on the right to food, said “lack of political will and a lost sense of urgency have unacceptably delayed decisive action” following a previous spike in food prices two years ago.

The Rome-based UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has called a special meeting to discuss the effects of rising food prices for September 24.

Although the world cereal output in 2010 should still be the third highest on record, fears about future supplies have led the prices of wheat to increase 70 per cent on international markets since last year, according to the UN.

Much of the recent wheat spike has been linked to drought and fires in Russia, which had been the world’s third-largest wheat exporter, and a decision by the Russian government to extend a grain export ban until late 2011.

The floods in Pakistan, Asia’s third-largest wheat producer, have destroyed 500,000-600,000 tonnes of wheat seed stocks and at least 1.3 million hectares of standing crops of maize, rice, sugar cane, cotton, vegetable and fruit orchards, according to partial estimates from FAO.

In October 2009 the FAO said 1.02 billion people were undernourished, up from its 2006 estimate of 854 million people.

The different varieties of seeds cultivated in Switzerland are conserved at the national seed bank at the Agroscope Changins-Wädenswil plant science research station in Changins, near Nyon in canton Vaud.

This collection has existed since 1900 and comprises some 10,000 different kinds of cereal, fruit and vegetable seeds. The national collection is complemented by others created by private individuals.

The aim of the national collection is twofold: to conserve local varieties that are neglected by farmers and to build up a reserve that could be used if needed.

The length of time seeds are conserved depends on their individual characteristics and varies from 50 years for wheat to 15 years for beans, peas and soya.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=bb19e376)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.