Stable Switzerland rests on shaky ground

Switzerland sits atop a fault line, which regularly sends tremors rippling through the “terra firma”.

Although the last catastrophic earthquake occurred more than 600 years ago, experts say another could strike at any time.

“When I submitted a draft law on earthquake precautions and intervention measures, I was asked if I had nothing better to do,” said the Swiss environment minister, Moritz Leuenberger, in a recent interview.

“But if a disaster of this kind were to occur tomorrow, I would be treated as incompetent and it would provoke a political outcry.”

As far back as 1874, the Federal Constitution made it incumbent on the Swiss government to adopt all necessary measures to deal with natural disasters, such as avalanches and flooding.

But there was no mention of earthquakes. And, without this constitutional mandate, the country has no system in place to cope with a natural catastrophe that could be as devastating as the quake, which hit the Japanese city of Kobe in 1995.

The lack of concern can perhaps be attributed to the fact that the country has faced far more pressing dangers – from wars to epidemics. Or perhaps it’s because the last catastrophic earthquake happened such a long time ago.

Not immune

Yet Switzerland is anything but immune from an event of this kind, says geologist Gaetan Rauber, who recently staged an exhibition devoted to seismic phenomena at Fribourg’s natural history museum.

“Our aim is not to frighten people, but to draw attention to the fact that a devastating earthquake could occur in Switzerland, even though the risk is reckoned to be fairly minor.”

Certainly Switzerland is not sitting on a “seismic powder-keg”, like Japan or California, but it is nevertheless part of a fairly delicate geo-seismic area.

Situated at the heart of Europe, Switzerland lies on the edge of the Eurasian tectonic plate. The border of this plate – and hence the area of friction with the neighbouring African plate – follows the line of the Alps.

Basel, on the other hand, sits squarely in the centre of the so-called “Rhine rift valley”, a fault in the Earth’s crust which opened up 30 million years ago when the Eurasian continent fractured along a line running from the North Sea to Switzerland.

Ravaged

Basel’s precarious position became apparent in 1356 when the region was ravaged by the most severe earthquake ever registered in Europe north of the Alps. The city on the Rhine was completely destroyed by a quake estimated to have reached 6.5 on the Richter scale.

Eleven centuries earlier, in 250 AD, the Roman city of Augusta Raurica, a few miles from Basel, suffered the same fate.

Other parts of Switzerland have also experienced scares – although not on the same scale. In 1601, a violent earthquake sent tons of rock into Lake Lucerne. The result was a small “tsunami”, a wave several metres high which then swept into the city of Lucerne.

“It is impossible to predict when similar catastrophes might occur in Switzerland,” says Rauber. “All we can say is that there is a major risk in a particular region. But a catastrophic event might not happen for decades, centuries or even millennia.”

Blissfully unaware

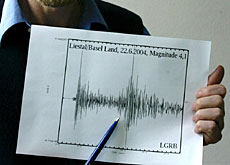

In Switzerland, tremors registering one or two on the Richter scale are a daily occurrence though most people remain blissfully unaware of them.

Tremors measuring three to five on the scale are recorded on average every ten years, and these are strong enough to cause damage: subsidence, landslides affecting roads and dwellings, and the collapse of poorly maintained buildings.

Shocks approaching six degrees on the scale, which are still relatively benign, can be expected to occur every 100 years. Quakes of greater magnitude, which often have dramatic consequences, are forecast to happen only once every 1,000 years – on average.

Today, an earthquake like the one that flattened Basel over 600 years ago would kill thousands and cause damage estimated at between SFr40 and SFr80 billion.

The Kobe quake in Japan, for instance, claimed 6,000 lives and caused damage totalling SFr100 billion.

Insurance companies in Switzerland are less complacent about the danger than politicians. They have limited earthquake cover to SFr2 billion, which means the state would likely have to foot the rest of the bill.

Precautions

Rauber’s exhibition at the Natural History Museum in Fribourg emphasises the importance of precautionary measures. These are still seriously deficient in Switzerland, and will remain so until the Federal Parliament adopts the necessary legislation.

The measures that have been introduced are unlikely to provide much protection in the near future. Most buildings, for example, do not comply with anti-seismic safety regulations, which were introduced 15 years ago.

One reason is because 90 per cent of all buildings were erected before 1989, and the cost of strengthening dwellings in the most danger-prone areas is very expensive, generally amounting to between five and ten per cent of the value of the building itself.

swissinfo, Armando Mombelli

Experts say Switzerland could be hit by an earthquake comparable to the one which devastated the Japanese city of Kobe in 1995, claiming 6,000 lives and causing damage of SFr100 billion.

A consultation procedure has begun to include an article on earthquake precaution measures in the Federal Constitution.

250 AD: an earthquake destroys the Roman city of Augusta Raurica, a few miles from Basel.

1356: shocks measuring 6.5-7 degrees on the Richter scale raze the city of Basel to the ground.

1601: a violent earthquake causes serious damage in the Lake Lucerne region.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.