Stem cell breakthrough won’t cure all ills

A new technique enabling a stem cell to be extracted from a human embryo without destroying that embryo has received a guarded welcome from Swiss scientists.

But the discovery is seen as more important for its scientific value than for the ethical dilemmas that it has supposedly resolved.

Since stem cells were first extracted successfully from an embryo in 1998, the field has been dogged by concerns over the ethics of killing a “potential human being” for research purposes.

Swiss law – in line with that of many other countries – allows cells to be extracted only from “spare” embryos, created as part of the process of in-vitro fertilisation and destined to be destroyed anyway, subject to the agreement of the couple concerned.

Now an American team led by Rob Lanza has succeeded in taking a cell from a three-day-old embryo consisting of between eight and ten cells (a blastomere), without destroying it. The discovery was reported in the scientific magazine Nature.

It has been possible to extract cells from embryos for some time. Last year, Lanza managed to perform the operation on a mouse embryo. And a similar technique is already practised in pre-implantation genetic diagnosis.

This method, controversial and for the time being prohibited in Switzerland, involves taking a cell from an embryo produced through in-vitro fertilisation and analysing it to detect any genetic disorders. If the diagnosis reveals no problems, the embryo can be implanted into the mother where it should develop normally.

One cell cures all

The ground-breaking aspect of Lanza’s discovery entails the possibility of producing a stem-cell line from just one cell.

“Scientifically, the article gives us more information on the possibility of getting a single cell to multiply,” explains Marisa Jaconi, the first Swiss researcher to work with stem cells. “Before, this was possible only with cells of animal origin.”

For the Geneva University biologist, the technique opens up new prospects for research. “When performing pre-implantation diagnosis, it would be possible to obtain stem-cell lines from embryos presenting possible congenital defects. This would allow researchers to study such cells, identify defects and develop new therapies for incurable diseases.”

Jaconi hopes the discovery might defuse – at least to some extent – the ethical problem associated with stem cell research.

“The fact that the embryo is not destroyed in this case deprives those opposed to this type of research of many of their arguments. However, the link with in-vitro fertilisation remains, and for some people fertilisation is an unacceptable manipulation.”

Cautious

More cautious is Carlo Foppa, a clinical ethicist and a member of the National Ethics Committee in Human Medicine. “The new technique gets round one major obstacle,” admits Foppa, who stresses that he is expressing a personal view. “But it may be that other problems will arise.”

These include the possibility of creating a whole new embryo using the cell taken from a blastomere.

Foppa also counsels caution about the possibilities of stem cell research. “Apart from a few experimental treatments for heart problems or Parkinson’s Disease, the promised breakthrough has just not happened.”

“Meanwhile, people are wondering where the embryos used for research purposes should come from,” observes Pascale Steck of the Basel Appeal against Genetic Technology, an organisation opposed to stem cell research.

“Should couples resorting to in-vitro fertilisation be asked, as a general principle, to make the embryo available for a “stem cell donation” before it is implanted into the mother?

“And who decides what the resulting stem cells can be used for? The human being who later develops from the embryo?”

swissinfo

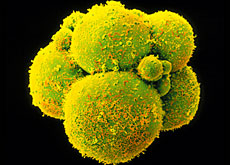

Stem cells are as yet unspecialised cells, which can develop into any part of the human body.

Because they have this potential, it is hoped that one day it will be possible to use them for combating degenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or diabetes.

Stem cells are present mainly in the early stages of life, when the cells of a fertilised egg begin to multiply.

Stems cells are also found in the umbilical cord and in the adult organism, but their potential is more limited.

In November 2004, Swiss voters approved by a large majority a law permitting stem cell research.

Under this law, scientists need a permit from the Federal Office of Public Health to conduct research and this must be directed towards obtaining information that will help in combating serious illnesses or explaining developmental biology.

Couples producing embryos used for research must be properly informed. Embryos may not be bought or sold. It is forbidden to produce embryos specifically for research purposes, to use them after the seventh day of development, to genetically manipulate stem cells, to create clones, and to patent unmodified cells.

Pre-implantation diagnosis is a way of examining the embryo before it is transferred to the mother’s womb during a medically assisted reproduction procedure. Using this method, it is possible to analyse embryo cells from the third day of their development and screen them for genetic abnormalities.

The technique is not permitted in some countries, such as Austria, Germany and Switzerland, though it is allowed in, for example, Italy. However, last year the Swiss parliament voted in favour of authorising PID, and legislation is now being drafted.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.