Switzerland now has a Professor of Gender Medicine. She’s here to stay.

SWI swissinfo.ch met Carolin Lerchenmüller in Zurich shortly after she was appointed Switzerland's first professor of gender medicine. She says it will take time to fully understand how and why women react differently to some diseases and treatments - but adds that that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

As the first academic to ever be named professor of gender medicine in Switzerland, Carolin Lerchenmüller does not want to be seen as a “mascot” or a figurehead. Her main challenge is to raise awareness of the importance of gender medicine, to ensure that her research is reliable, and that her legacy lives on beyond the hype.

“I’ve been extremely busy moving to Zurich, dealing with media and presentation requests, visiting numerous conferences, building my team, filling vacancies and developing our research and teaching programmes,” she tells SWI swissinfo.ch at the University of Zurich, where she is now based.

It took three months to arrange to meet Lerchenmüller, who started her new job on May 1. Her office was not yet fully furnished so we interviewed her in a meeting room on campus.

Gender medicine makes a long journey to Switzerland

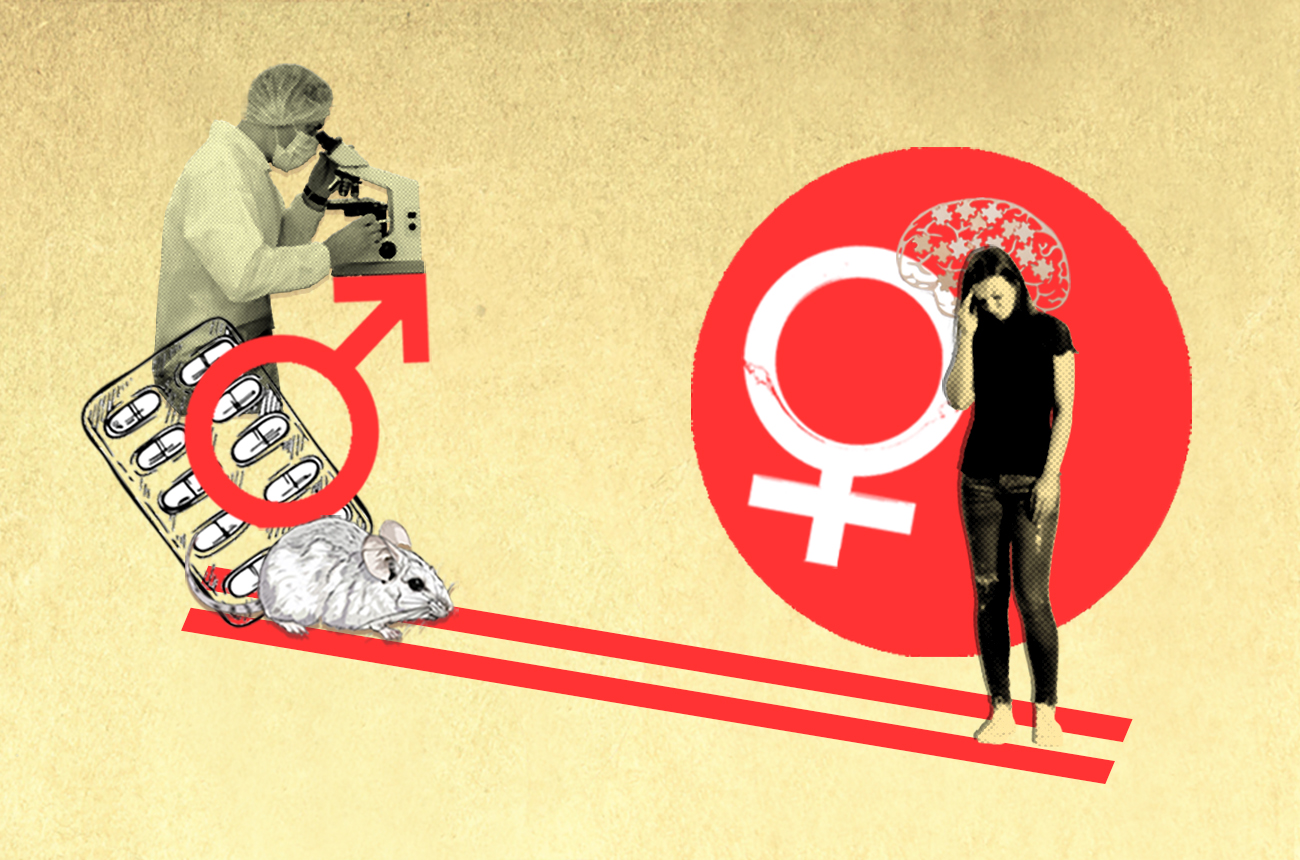

Gender medicine, also known as sex- and gender-specific medicine, is the study of how sex and gender-based differences influence people’s health. It seeks to better understand gender-specific differences in biology and social behaviour and incorporate these into patient care, teaching and the development of treatments.

The discipline emerged in the United States more than 40 years ago, when feminists joined hands with cardiologists to study how heart disease affects women differently than men. In 1993, the US Congress mandated that Phase III clinical trials (the last phase before requesting approval for the drug’s release on to the market) include both sexes in adequate numbers to ensure that the data can be analysed for an effect on gender.

It took another 20 years or so for gender medicine to gain momentum and find its way into medical schools in Europe.

Sweden took the lead. In 2001, the medical faculty at Umeå University decided to integrate gender perspectives in its medical curriculum. The country’s Karolinska Institute was the first in Europe to establish a web-based educational course on health and disease from a gender perspective.

In 2003, the German cardiologist Vera Regitz-Zagrosek founded the Berlin Institute for Gender in Medicine (GiM), the first interdisciplinary research centre in Europe to take a systematic approach to integrating sex and gender medicine into medical and inter-professional education.

By comparison, Switzerland has been a relatively slow starter. It was only in 2019 that the University of Lausanne’s Centre of General Medicine and Public Health (Unisanté) created a health and gender unit.

The country also has a poor record of promoting women in the medical field. In 2017, Switzerland launched the Women in Cardiology (WIC) group, a platform for female cardiologists to share their expertise. Its counterpart was launched in the US back in 1994 and in the United Kingdom in 2005.

Finding a gender-medicine role model in the US

Lerchenmüller first encountered gender medicine as a cardiologist during her studies at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School between 2013 and 2017. One of her role models at the time was Marianne Legato, an American cardiologist who was the first to recognise and systematically describe differences in cardiovascular diseases between men and women.

“The differences between women’s and men’s hearts were well recognised and actively researched where I worked,” she says of her experience in the US.

While men typically suffer from chest pain radiating into the left arm, many female patients display completely different symptoms, including shortness of breath, sweating, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, and head or neck pain.

This difference in symptom perception can be fatal: “Doctors have sometimes dismissed life-threatening conditions in women and sent them home,” resulting in a significantly higher risk of misdiagnosing a heart attack in women, says Lerchenmüller.

Determined to make her mark in this new field of study, she returned to her native Germany to lead a research group in the Department of Cardiology at the University of Heidelberg, with the goal of studying and incorporating gender differences in her work.

“I was very motivated. I thought, this is my niche! This is where I really want to leverage my new knowledge,” she says. But she was quickly disappointed. Shortly after returning to Europe, she noticed a stark gender imbalance in cardiology in Germany. For example, very few women were invited to give talks at the annual congress of the German Society of Cardiology (DGK) at that time. “That was not a good sign, because it would eventually influence our scientific focus,” she says.

This led her to launch an initiative for women at the German Cardiac Society to promote the representation of women in cardiology, especially in leadership positions. She went on to lead the Women and Family in Cardiology group within the German Cardiac Society to build a foundation for evidence-based gender equity and to promote diversity.

Carolin Lerchenmüller has been Professor for Gender Medicine at the University of Zurich since May 1, 2024. She is the first professor with this specific title in Switzerland. She works as an attending physician in the Department of Cardiology at the University Hospital Zurich.

Previously, she was a research group leader and head of the Laboratory for Cardiac Remodeling and Regeneration at the University Hospital Heidelberg, where she also worked as a cardiologist, and a principal investigator at the German Center for Cardiovascular Research.

Establishing gender medicine as a full-fledged discipline

When the position of Switzerland’s first professor of gender medicine was advertised, Lerchenmüller was one of the few candidates to apply for the professorship at the University of Zurich. The position was advertised as developing individualised diagnoses and therapies for men and women, in order to better understand the needs of men and women in the medical community and the corresponding structures that cater to them.

To support the work, Lerchenmüller is hiring several postdoctoral students and a technician to conduct fundamental research. She will also be researching how to generate high-quality and reliable data based on a systematic review of empirical evidence through international collaborations.

Lerchenmüller says her first challenge will be to go beyond the hype around gender medicine and establish her field of study as a full-fledged academic discipline that can continue to evolve.

“It’s easy to create a new research area or professorship in gender medicine, but it’s quite difficult to make this work sustainable,” she says.

The questions she asks herself don’t come with easy answers. Why do some diseases affect men and women differently? And why do they sometimes respond differently to drugs?

“There is currently not enough data on these differences,” she says. “This is the challenge facing academia, clinical medicine and the pharmaceutical industry.” She points out that there are many data gaps that have developed over decades and need to be filled.

More

Drugmakers are finally making medicine for women

One reason is the underrepresentation of women in clinical trials. This bias continues when drugs are developed and manufactured. “It’s probably fair to say that most of the drugs we use are designed for the 80-kilo white male,” says Lerchenmüller.

Producing quality evidence ‘a necessarily slow process’

Lerchenmüller says it will take decades to close the data gap. As an example, she cites the fact that differences in heart attack symptoms between men and women were known as early as the 1990s but it took another 20 years or so for these differences to be mentioned in European guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice.

“There has to be solid data to confirm and explain the differences we have observed, in order for those differences to be recognised in guidelines,” Lerchenmüller explains.

Although many have complained that the pace of change in gender medicine is slow, Lerchenmüller disagrees. She believes that it takes time to produce high-quality, reliable evidence to create guidelines that can be translated into clinical care and be applied worldwide. “It’s necessarily a very slow, very careful process,” she says.

One of the most striking and cautionary tales of gender disparities driven by insufficient data and inaccurate science is the controversy surrounding Zolpidem, sold under the brand name Ambien in the US.

The drug, commonly prescribed as a short-term solution for people suffering from insomnia, is best known for being the cause of deadly headline-grabbing car accidents. In a landmark decision in 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration recommendedExternal link that women take half the dose of the drug compared to men. The FDA cited new data published by the Center for Drug Evaluation and ResearchExternal link, which indicated that women were at higher risk of cognitive side effects the next day that impacted driving. The data showed that this was because women metabolise the drug more slowly than men. This was the first and to date only sex-specific drug authorised by the FDA in the US.

However, several researchersExternal link have since questioned the reasoning behind the FDA’s recommendation, saying that it lacked “concrete evidence”. They say the FDA’s recommendations may led to under-medication for many women suffering from sleep disorders.

One major task for Lerchenmüller and her team will be to connect databases and find more collaborations at the national and global levels to collect data on gender differences.

Switzerland plays catch-up

Three months into her job, Lerchenmüller says she is pleasantly surprised by the quality of research in Switzerland. “The research and healthcare work in gender medicine that’s being done here is really great – far beyond my expectations,” she says.

Over the past two years Switzerland has been catching up on developing the field in its medical curriculums.

The universities of Bern and Zurich launched the country’s first advanced training in sex- and gender-specific medicineExternal link in autumn 2020. Their aim is to present tools, concepts and ideas on how healthcare and medical research in various medical disciplines can be gender equitable.

The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) launched a call for the Swiss National Research Program to research “Gender Medicine and Health”External link at the end of 2023, with a budget of CHF11 million ($13 million), out of a total annual budget of CHF1 billion. Approximately 140 pre-proposals were submitted by 389 researchers, almost half of all applications submitted for all national research programmes. The next evaluation phase will take place this fall.

Like other female physicians and researchers, Lerchenmüller says her personal life is scrutinised differently than that of her male colleagues. She remains elusive about how she is juggling raising three children alongside a challenging job. She wants to keep the focus of the interview on her work and her vision, rather than on the fact that she is the first woman and – first person – in Switzerland to hold such a position.

She believes that real progress to advance women in healthcare and medicine depends on making the entire field more diverse and equitable.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/gw

Corrections: The Swiss National Science Foundation budget is CHF1 billion not 47 million. And UniSanté created a health and gender unit in 2019 not courses.

More

Our science newsletter

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.