Taking the fight against cancer a step further

Despite real progress in tackling cancer, the more scientists find out about tumours the more complex they appear, says Nobel prize-winning researcher Tim Hunt.

Hunt, a leading scientist at Cancer Research UK, talks to swissinfo about the fight against cancer and his research into cell division.

The friendly, slightly eccentric professor – sporting a T-shirt full of holes – was in Switzerland to deliver a lecture at the “Cancer and the Cell Cycle” symposium at Lausanne’s Federal Institute of Technology.

Hunt won the Nobel Prize for medicine in 2001, together with Lee Hartwell and Paul Nurse, for their discoveries of key regulators of the cell cycle that radically altered our understanding of how cancer operates.

swissinfo: Some scientists say there will never be a “cure for cancer”, but that over time it could be demoted to the status of a chronic disease that people could live with. What’s your feeling?

Tim Hunt: I think there have been real advances and at least for some of these diseases it’s possible to contain them. But you have to take it tumour by tumour.

My mother died of colon cancer almost 30 years ago and by the time she was diagnosed she didn’t have much of an inside left. I have a friend who was recently diagnosed with colon cancer and they caught it in time and the prognosis seems to be remarkably good. There really has been a revolution in the treatment of this disease.

Another good example is my mother-in-law who in 2001 was 82. They thought she was depressed but discovered she had a tumour the size of a grapefruit in her head, which they then cut out. Seven years later, she is still doing really well.

It remains true that if you have a tumour that you can cut out cleanly, bang, the tumour is gone and that’s it. Chemical control is not nearly as good, as you always get resistance building up.

And prevention is far better than a cure. If you smoke you raise your chances of getting lung cancer astronomically, and if you don’t smoke or go near smokers, it’s a very rare disease.

swissinfo: What recent research developments are helping to further our understanding of cancer and the cell cycle?

T.H.: The advances are coming in the understanding of the control of cell growth, but that’s really complicated as cell growth means everything a cell has in it: more proteins, DNA, RNA [ribonucleic acid], membranes, absolutely everything. And not surprisingly the controls and keeping those things coordinated is complicated and very poorly understood.

But people are starting to understand the enzymes – the master regulators – that control and coordinate growth.

swissinfo: Where would you like to see greater scientific focus?

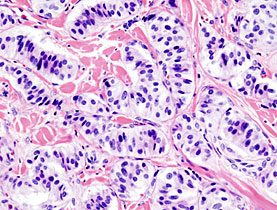

T.H.: We still have an awful lot to understand about the fundamentals of not only cell biology, but also how cells make organs and how organs relate to each other and how tissues talk to each other. That’s where I see things going wrong in tumours.

Going back to my mum, one of the things that struck me very forcibly was that the cancer cells were growing and she was shrinking – all her muscles were wasting away. How could the cancer cells suck all the goodness out of her fat and muscles? If I had my life again I would love to look at that.

And a very famous German biochemist from 1930s Otto Warburg found that tumours had a different metabolism from normal cells. We still don’t really understand the biochemical basis of that. One feels there are clues that deserve following up.

The trouble today is that techniques for analysis in some respect run much faster than our brains and our ability to make sense of all this amazing amount of data.

People are still desperately trying to make sense after an initial phase of optimism where they thought we can take a cell out of a tumour, sequence the DNA, classify it and know exactly what treatment to give this person for a particular tumour.

In principle DNA analysis ought to allow you to say this is type 1, 2 or 43, but it turns out that there are almost as many different kinds of tumours as people with tumours.

The more we find out the complexity becomes bewildering.

swissinfo: What advice would you give to ambitious young scientists?

T.H.: I always tell them to keep their nose to the grindstone and eyes on the horizon.

Very often tackling a problem comes about from a completely random observation. When you are thinking along conventional lines you often can’t see the wood from the trees or even the trees at all. Opening your eyes is terribly, terribly important.

As a scientist it feels all the time that we operate in a kind of fog and every so often the mist clears a bit and you can see where you are and you run forward and then the fog comes down again and you go round and round in circles. It’s a funny business.

swissinfo-interview: Simon Bradley

After cardiovascular diseases, cancer accounts for the second-highest number of deaths in Switzerland; 28% of men and 22% of women die from the disease.

Every year, 31,000 new cases of cancer are recorded in Switzerland, and 15,000 cancer-related deaths.

Worldwide, cancer kills 11 million people a year (12.5% of all deaths).

Tim Hunt studied natural sciences at Clare College, Cambridge University, and received his PhD from there in 1968. He did his postdoctoral work at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York and at Cambridge University, where he became a research fellow and lecturer.

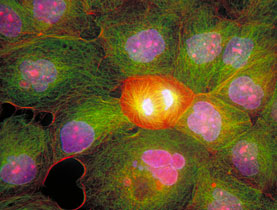

In the 1980s Hunt uncovered a key protein in cell division called a cyclin, another piece in the jigsaw of checkpoint regulation necessary for healthy growth. His discovery in sea-urchin eggs that the levels of cyclin increase greatly as cells approach division, but then disappear, suggested that cell proliferation could eventually be artificially controlled by turning off or destroying these activating elements.

In 1990, he joined Cancer Research UK. Tim Hunt is a Fellow of the Royal Society, and the recipient of many honours, including the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2001, which he received jointly with Paul Nurse and Leland Hartwell.

The World Cancer Congress takes place every two years.

It is organised by the International Union Against Cancer.

Objectives include translating research into practical applications, understanding the economic effects of treatment and determining best practices.

The congress also aims to build capacity among member organisations, implements programmes including tobacco control and develops partnerships between rich and poor countries.

The first meeting, called the International Cancer Congress, took place in 1933 in Madrid.

In 2006, it was held in Washington, and moves to Beijing in 2010.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.