The Swiss have to eat less meat by 2050. Here’s how.

Meat dominates the Swiss diet and agriculture, but that will have to change for the country to reach its climate goals by 2050. Trends like increased chicken consumption worry experts. Yet, there is a way out.

You have probably already heard the argument many times before: that you should eat fewer animal products, especially meat. I changed my diet two years ago, as chronicled in this series, and now I only eat meat once or twice a month.

I was very surprised when the Swiss government started to promote diets containing less meat to reduce carbon emissions and achieve its climate goals by 2050. This was coming from a country known for its state-subsidisedExternal link cows and where many farmers sit in parliament and defend the strong Swiss tradition of meat and milk products.

Check out our selection of newsletters. Subscribe here.

But Switzerland’s climate strategyExternal link clearly states that meat consumption is “still too high”. This is true. The meat available in Switzerland (more than 50kg per person per year) is lower than in France, Spain and Germany but still around twiceExternal link the global average.

But the government’s strategy lacks specific measures to convince people to eat less meat and consume more plant-based products, say experts.

“Without consumer participation, this strategy is just a piece of paper,” says Michael Siegrist, a professor at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich.

Siegrist, who has been studying consumer behaviour for almost 20 years, knows that it is very difficult for people to voluntarily change their eating habits. “If people don’t see an incentive, they won’t do it,” he says.

Meat substitutes remain a niche. After an initial boom, sales have stagnated, according to a survey by Coop SwitzerlandExternal link, one of the country’s largest retailers. Consumers citeExternal link high prices and health concerns related to processed products as reasons for not buying more of them.

Researcher and agronomist Priska Baur, however, sees the government’s strategy as an important step forward.

“A year or two ago it would not have been possible to mention the reduction of meat consumption,” she says. Baur, who heads the NovanimalExternal link research project for a healthy, nature-friendly diet, has been a vegetarian since her teens. She says she would only go back to eating meat if she herself killed the animal she intended to put on her plate.

“I have worked in agriculture. I would know how to do it… but I don’t want to,” she says.

Baur acknowledges that the road to reducing meat consumption in Switzerland is fraught with obstacles. Not only is meat still central to Swiss food culture – think sausages, meat fondue or Zurich-style veal stew – but it also dominates the country’s agricultural production.

Less beef and pork, more chicken on Swiss plates

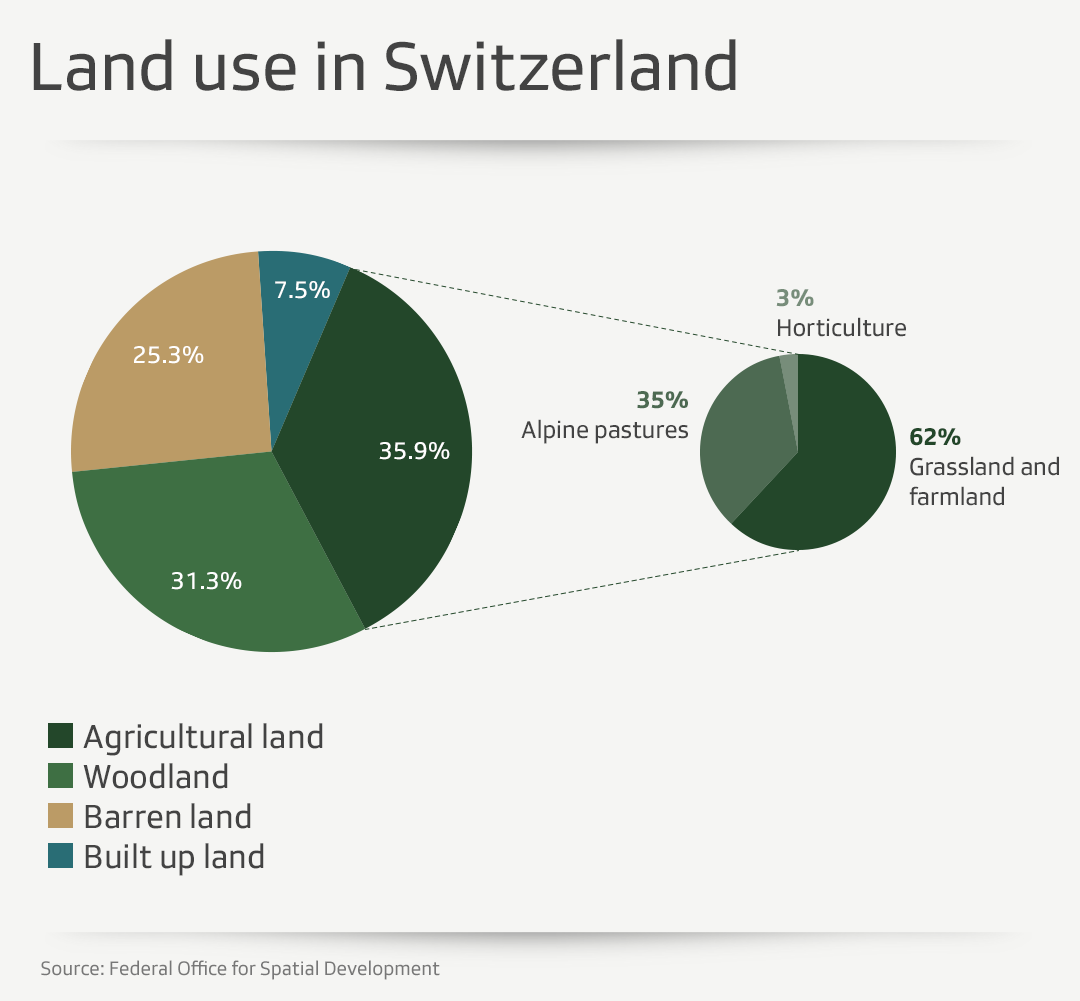

In Switzerland, agriculture is dominated by meat and dairy products and is responsible for more than 15%External link of the Alpine country’s greenhouse gas emissions. Reducing emissions would also require reducing the number of farm animals, but this is not explicitly mentioned in the government’s strategy, says Baur.

Overall, she doesn’t see significant changes underway. Meat production, for example, has been growing since the 1960s, as has consumption, “although politicians would have us believe otherwise,” says Baur. The 2023 federal agricultural reportExternal link shows that although people are eating less beef and pork, chicken consumption is growing steadily.

This is a global trend: poultry consumption has tripled in the last 60 years, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)External link.

People believe that it is better to eat chicken than other types of meat, as it is considered healthier and less environmentally problematic. Unlike cows, chickens do not emit methane. But chickens do not graze on grass and are totally dependent on feed, especially soy, which Swiss farmers import cheaply from abroad. Consumers are also attracted by the generally lower price of poultry.

“Chickens are replacing other meats,” says Baur.

Switzerland is chicken country

When it comes to counting the number of farm animals in Switzerland, Baur is not fooled by appearances. She claims that the federal government’s statistics are misleading and opaque, primarily because “the calculation is done on a specific day and not over a whole year. But this does not take into account that the life span of chickens is very short.” she says. On industrial farms, chickens are slaughtered after about one month of life.

Baur did her own maths over a year instead of a day and found that by 2022 the number of farm animals in Switzerland exceeded 96 million, 94% of which are poultry. By comparison, the Federal Statistical Office and Agristat reported 16.6 million animals on Swiss farms the same year. The number of poultry slaughtered in Switzerland in 2022, around 80 million according to ProviandeExternal link, confirms Baur’s calculations. This means that there are more than 10 chickens per Swiss resident, not including the large amount of imported chicken meat.

Two-thirds less meat and grass-fed cows

But isn’t Switzerland better known for cows grazing in the beautiful mountain grasslands? Yes, and this is the way forward for more ecological agriculture, argues Matthias Meier, professor of sustainable food systems at the Bern University of Applied Sciences.

More than 60% of the agricultural area in Switzerland consists of permanent meadows that cannot be used for crops. Therefore, using them as pastures for cattle and sheep is the only way to make them profitable. “We need ruminants. But the problem today is that we have too many animals and we produce too intensively,” says Meier.

Meier argues that in future, Switzerland should only feed cows with grass. This way, feed would no longer have to be imported and most of the arable land used for animal feed could be dedicated to grow crops for human consumption. It is a model that Germany, Sweden, Italy and some Swiss farms are already experimenting withExternal link. The Swiss government also mentions it in its strategy. Under such a model, cows would produce less milk and less beef, as they would not be overfed with concentrated feed (containing mainly soy proteins and cereals) meant to fatten them up.

This, says Meier, would result in our eating two-thirds less meat while having more sustainable production and a more varied diet.

“We don’t have to completely eliminate meat and milk, which are valuable sources of protein,” he says. Although he describes himself as a ‘part-time vegan’, he is among those who do not believe that veganism is the solution. Both in Switzerland and around the world, the extent of arable land is too limited and it is more complicated to assimilate all the necessary micro- and macronutrients with a plant-based diet.

Part of me is relieved. I, too, can be a ‘part-time vegan’ without feeling too guilty. It is the quantity that makes the difference.

Someday, whether we want to or not, we will all be forced to change our eating habits, says Meier, because the resources and raw materials to sustain today’s production of meat and other animal products will start to run out.

“Climate change will give us no other choice,” he says.

Edited by Sabrina Weiss and Veronica DeVore.

Priska Baur contributed to data collection for this article.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.