Urban flooding slowly becomes a priority issue for Switzerland

Climate change is pushing Switzerland to change the way it handles urban flooding. As flood risks grow, cities and towns are implementing innovative ways to mitigate the risks.

For many older people in Melchnau, a village with 1500 inhabitants in canton Bern, the year 1986 will never be forgotten. They all experienced a “collective trauma” due to the flood damage.

Christian Eicher, a retired civil engineer who worked on flood control and urban drainage, told SWI swissinfo.ch that historic news records show that on June 20 that year, an extremely heavy thunderstorm hit the area. “The streets of Melchnau flooded, as more than 50mm of rain fell per hour. Houses and meadows flooded, and roads were ripped open. The major urban thoroughfare was swamped by up to one metre of water.”

“In 1986, the local government had little experience in preparing an urban flood-management plan and had no idea how much it would cost. Despite this, the government commissioned an early Risk Map, which included extreme-runoff flow estimates – but there was no concrete follow-up to reduce the flood flows or protect against them,” Eicher explained.

About twenty years later, in 2007 and again in 2010, heavy thunderstorms with extraordinary rainfall volumes, combined with previous rainfall and saturated soils, led to widespread flood damage and traffic disruptions. Eicher followed up on the two floods, documented them with photos, and reported to the municipal authority with preliminary suggestions for action to show how frequent and devastating the floods had been over the past three decades.

Urban flooding is a global issue

Melchnau is not an isolated case in Switzerland. Over the last 40 years, four out of five Swiss municipalities have experienced flooding, about two-thirds (62%) of buildings are exposed to surface runoff, and one in seven people in Switzerland live in a building exposed to flooding, according to the Mobiliar Lab for Natural Risks at the University of BernExternal link.

Floods are considered by Switzerland as a “secondary” perilExternal link, defined as independent, high-frequency, small- to medium-sized events that are more difficult to monitor than hurricanes and earthquakes. But this doesn’t mean that they don’t cause substantial damage.

The Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL) has been systematically recording and analysing flood damage since 1972. According to a report published in 2021External link, “floods are the natural hazard with the highest amount of damage in Switzerland”. A flood in August 2005 caused the most damage recorded in the WSL damage database – around CHF3 billion ($3.3 billion).

Climate change has pushed urban flooding to the forefront of local governments’ agendas and led to innovative solutions being implemented worldwide. A 2022 paperExternal link in the scientific journal Nature Communication says that 1.8 billion people, or 23% of the world’s population, are living in areas directly exposed to a 1-in-100-year flood risk. According to reports from the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, floods caused global damageExternal link amounting to an estimated $651 billion between 2000 and 2019 alone; the number of major floodsExternal link has also more than doubled during this period, from 1,389 to 3,254. Notably, losses from these events are expected to increase by a factor of 20 by the end of the 21st centuryExternal link.

Current dominant strategies to combat urban flooding

Australia has been known for its flood-control measures and innovative water-management approach since the 1980s, called Water Sensitive Urban Design. This strategy reduces stormwater flows and increases soil moisture using decentralized infrastructures like green roofs, permeable pavements, constructed wetlands, and rainwater tanks. Similar concepts in other countries include the United Kingdom’s Sustainable Urban Drainage System, the United States’s Low Impact Development, and Singapore’s Active, Beautiful and Clean Waters Programme.

In Denmark, Copenhagen is taking a novel approach to preventing repeated flooding. The ongoing SkybrudsplanExternal link, or Cloudburst Management Plan, costs €1.8 billion (CHF1.76 billion) and aims to transform the city into a “sponge”: the idea is to redesign public spaces and infrastructure so they can absorb and retain vast amounts of rainwater, much like a sponge would, during periods of intense rain, and release it back into the water cycle.

In China, 70 rapidly growing citiesExternal link have also adopted the “sponge city” concept to manage water flow and reduce the risk of flooding.

Prioritising urban planning as flood management solution

Switzerland has lagged behind other countries in implementing flood-management strategies. Only in 2018 did the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) and the insurance industry start developing and publishing the first Swiss-wide surface-runoff hazard map.

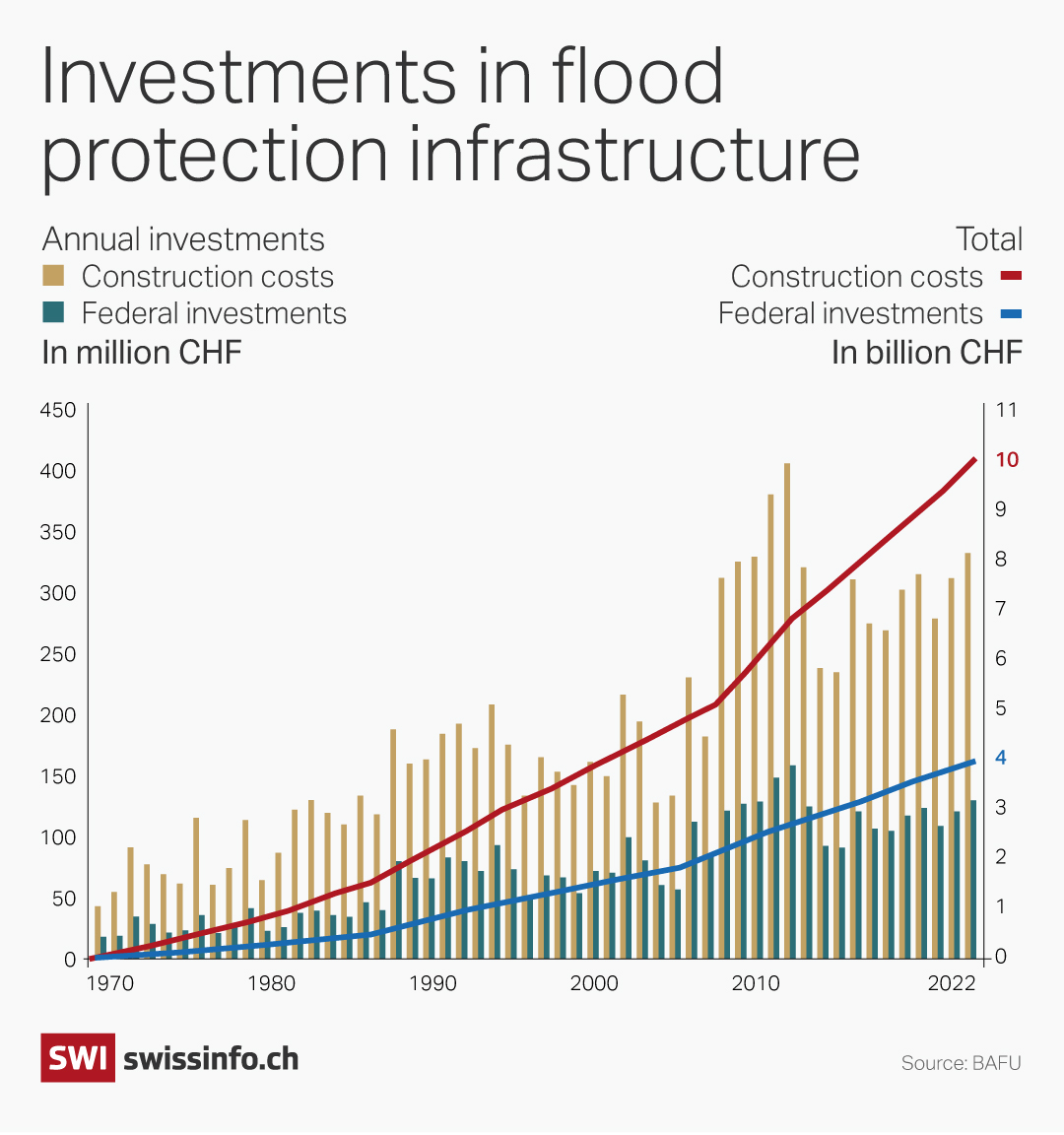

Swiss authorities report that annual financial investment in flood protection infrastructure was between CHF 50 million and CHF 230 million from 1970 to 2008. Since 2008, costs have increased significantly, fluctuating between CHF 250 million and CHF 400 million. However, this is still not enough to offset the damage from a rare, one-off flood. A 2020 publication by the Swiss Federal Office for Civil Protection (FOCP) shows that a very rare flood could cause damage exceeding CHF 10 billion.

Switzerland is a few years behind, but climate change is creating new challenges for Swiss urban planners and stormwater managers. “Only recently has Switzerland realized the significant impacts of pluvial flooding on infrastructure and socio-economic activities,” says João Leitão, head of the Urban Floods and Hydroinformatics group at Eawag. Although pluvial floods generally cause less damage per event than fluvial floods, their higher frequency means their long-term impacts can be similar.

The “growing pains” of Swiss cities and settlements also exacerbate the risk of urban flooding. Construction must keep pace with population growth and urbanisation. According to the World BankExternal link, Switzerland’s urban population nearly doubled between 1960 and 2022. Currently, almost three-quarters of the Swiss populationExternal link lives in urban areas, and around 80% of the country’s economic activity is concentrated there.

Based on what he has seen in Melchnau, Eicher says that more concrete and asphalt reduce water infiltration. “With concrete and asphalt covering areas that used to be grass and soil, heavy rainwater has nowhere to go, causing flooding,” he says. “Intensified agriculture, increased mechanization, and heavier machinery compact soils and reduce the important sponge effect of pervious surfaces. This leads to more, earlier, and faster runoff from surfaces that should retain most of the rainfall.”

The growing population and infrastructure in urban areas increase the risk of financial losses from floods. Robin Poëll, a spokesperson for the Federal Office for the Environment, says around 20% of the Swiss population lives in areas at risk of flooding due to their proximity to rivers and lakes. About 30% of jobs and a quarter of Switzerland’s material assets (CHF 840 billion) are in these areas.

Given the likelihood and potential damage, “flooding has become one of the dominant risks in Switzerland, and flood protection is a high priority on the Swiss agenda,” says Poëll.

More

Research and new technology for urban flooding prevention

The Swiss government is increasing investments in flood-protection infrastructure. However, Swiss researchers believe traditional urban flood management may not be enough for flood resilience. They are now exploring new strategies to combat urban flooding.

In 2018, the Mobiliar Lab for Natural Risks launched the Flood-Risk Research Initiative – From Theory to Practice. This initiative aims to develop tools to warn about upcoming floods and their effects. These tools will show the impacts of rising and receding floodwater on people, workplaces, buildings, and roads.

“For the first time, we can visually identify potential flood damage throughout Switzerland – down to the neighbourhood level,” says Andreas Zischg, a professor at the University of Bern who participated in the project. “We can see when, where, and how many people might need to be evacuated, and when and where roads might become impassable. This information can help local civilian command teams, insurance companies, logistics companies, and others with risk communication, training, and planning.”

In 2019, Leitão and his team developed a device called CENTAUR (Cost-Effective Neural Technique to Alleviate Urban Flood Risk). This device can be easily installed in existing drainage systems to reduce local flood risks in urban areas.

No Swiss city has adopted it yet, but it has been installed in Coimbra, Portugal’s fourth-largest city, and a few municipalities in the UK. Leitão says that managing urban pluvial flood risk in Switzerland is difficult because responsibilities are spread across many levels and sectors of government. Also, newer and older parts of cities have different drainage systems.

Complex distribution of responsibilities for flood-risk management

Like Germany and Austria, Switzerland has a complex system for managing flood risks. Responsibilities are spread across different levels and sectors of government. An innovative approach to water management and hydraulic engineering also affects urban planning, energy, nature conservation, and other areas.

However, progress is being made. Some Swiss cities have started using sponge city concepts in new projects to reduce flooding. Leitão mentions the VSA (Swiss Water Association) sponge city project, which promotes blue and green infrastructure to reduce flooding and stormwater discharges. This also helps improve ecosystem services, like reducing heat and increasing biodiversity.

When Eicher visits the river in Melchnau, he sees changes. In 2021, the municipality invested over CHF 4 million in a flood-protection project. This included building four retention facilities and widening the stream channel to reduce the risk of creeks overflowing. “Better late than never,” he says.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.