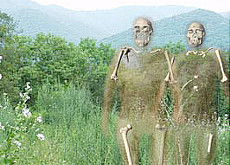

Zurich team rebuilds our ancestors

Ancient hominids from the Caucasus - possibly our earliest ancestors to migrate from Africa - walked and ran like modern man, new research has indicated.

The study in this week’s Nature magazine was assisted by the pioneering virtual 3D work of a team from Zurich University, world experts in the computer-assisted reconstruction of ancient fossils.

Dmanisi, in eastern Georgia, is one of the most important archaeological sites in the world. Over the past 16 years, the well-preserved remains of at least six individuals, dating from 1.7 million years ago, have been found in the Caucasus.

Scientists claim they are the earliest representatives of our own genus, Homo, outside Africa and the most primitive population of the Homo erectus species known to date.

Bones of three adults and one adolescent recently dug up in Dmanisi have now been associated with skulls found earlier. These discoveries have helped piece together the evolutionary puzzle and allowed an international research team to peer into the life and times of our ancestors, according to anthropologist Christoph Zollikofer.

“Dmanisi has won the lottery four or five times over; researchers haven’t just found a single bone or individual, but a whole population,” Zollikofer told swissinfo. Together with Marcia Ponce de León, he spent a year rebuilding the remains on their computers in Zurich using a groundbreaking virtual reconstruction technique.

Short, small-brained runners

Until now, little was known about the ‘erectness’ of Homo erectus, as their anatomy was almost exclusively known from skulls. Skeletal remains from that time are extremely rare.

The latest findings show that the Dmanisi hominids were not typical of the lean, tall-standing, big-brained Homo erectus – instead they were short, long-armed, small-brained and thin-browed.

“Small people have smaller brains, but even compared to their body size they really had tiny brains – less than half what we have today. They were much more similar to the Homo in Africa two million years ago than what we know about Homo erectus from later times,” he added.

“They were quite short – 1.4 to 1.6 metres tall at most – but had the same body proportions as ourselves,” said Zollikofer.

“The amazing thing is that the legs of these creatures were pretty modern. They had longer legs than arms and were capable of long-range walking and running,” he explained, adding that this greatly influenced their ability to forage.

The Dmanisi hominids were carnivores and it is thought they covered large distances in search of animal carcasses. In Georgia, they encountered cool, seasonal grasslands and forests, where African animals such as ostriches and giraffes mingled with Eurasian species such as wolves and the sabre-toothed tigers.

Their shoulders and arms were also quite distinct from those of modern humans, but this didn’t prevent them from producing basic stone cutting tools or from breaking up big game bones for the marrow, the study reveals.

Where are we from?

The Dmanisi discoveries continue to create a buzz among human evolution researchers, challenging existing theories about the origins of humans.

So far it has been difficult to determine exactly what species they are. Many experts claim it was Homo erectus who first migrated out of Africa and spread around Asia.

But the Dmanisi foragers were not typical of the first tall, upright, big-brained humans thought to have left Africa.

As a result some claim they may have been Homo habilis. But this fairly ape-like hominid was not thought to have lived outside Africa.

Other experts have coined the term Homo georgicus to describe the Dmanisi creatures – so the confusion continues.

“It’s difficult to decide at the moment,” said Zollikofer. “I think everything originated in Africa. The question is when did the first hominids leave Africa. Of course the Dmanisi hominids could be one of these very first dispersals.”

And to answer Zollikofer’s question, work continues at the rich wooded hilltop site in Georgia for more evidence of our distant relatives.

swissinfo, Simon Bradley

A generally accepted theory is that modern humans (Homo sapiens) emerged in Africa around 120,000 years ago, slowly replacing the older species there.

Homo sapiens moved out of Africa into Asia and the Middle East, reaching Europe 40,000 years ago.

Homo sapiens is thought to have displaced Homo neanderthalensis and other species descended from Homo erectus (which had colonised Eurasia two million years ago) through more successful reproduction and competition for resources.

A hominid is a member of the biological family Hominidae, the “great apes”, which includes humans and their fossil ancestors, chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans.

Paleoanthropology is the study of human prehistory through fossil evidence.

Dmanisi is the site of a medieval village located about 85km southwest of the capital Tbilisi in eastern Georgia.

In 1983 archaeological excavations in the ruins of the old city led to the fortuitous discovery of Plio-Pleistocene sediments containing animal bones.

Scientists later unearthed complete skulls, numerous other bones and stone tools belonging to six early humans from about 1.7 million years ago.

Christoph Zollikofer was born in Zurich and started studying biology at Zurich University. He then studied cello for three years before returning to the university to complete a neurobiology PhD on the locomotion of desert ants. He has been professor of anthropology at Zurich University since 2004.

Marcia Ponce de León was born in La Paz, Bolivia. She studied civil engineering and was also a serious piano student. In the mid-1990s she moved to Zurich to study biology. In 2000 she received a PhD in anthropology, focusing on Neanderthal development. She is currently senior lecturer of anthropology at Zurich University.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.