Swiss glaciers surrender secrets of the past

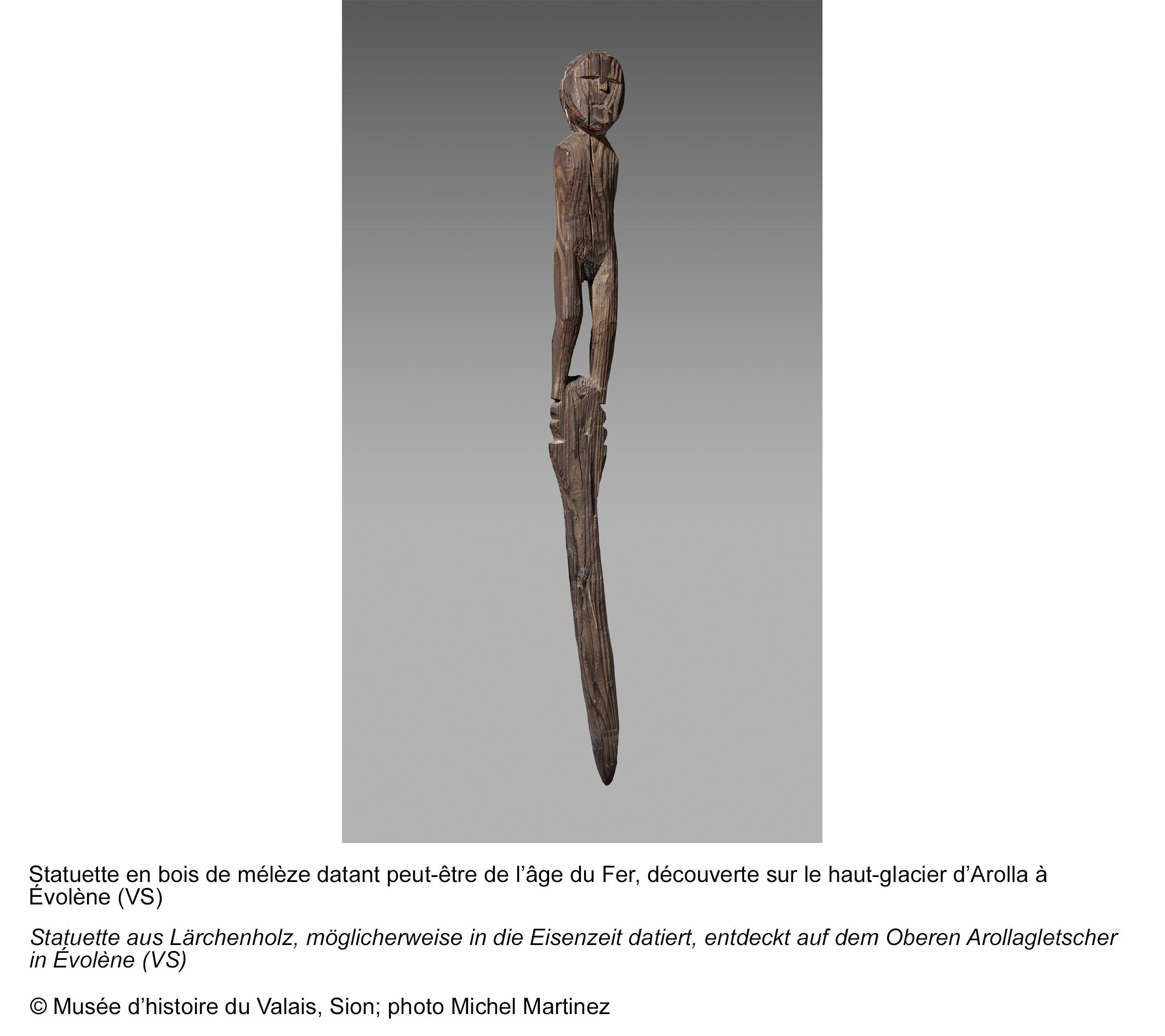

Neolithic wooden bows, quartz arrowheads and a prayer book: As Alpine glaciers melt and retreat, well-preserved archaeological treasures and human remains are surfacing. A new exhibition presents some of the rare finds.

“If you are on a glacier, any piece of wood you find is likely to have been brought there by a human. If the wood looks unusual and like it’s been worked upon by man, you should contact the archaeological service about it,” declares Pierre-Yves Nicod.

The archaeologist and Valais History Museum curator recently inaugurated the “Mémoires de glace: vestiges en péril” [Icy memories – vestiges in danger] exhibition in the town of Sion,External link a small but important collection of objects dating from 6,000 BC up to the last century, which had been frozen in time beneath Alpine glaciers. Most were found by hikers or skiers at high altitude and later verified by archaeologists using carbon-dating techniques.

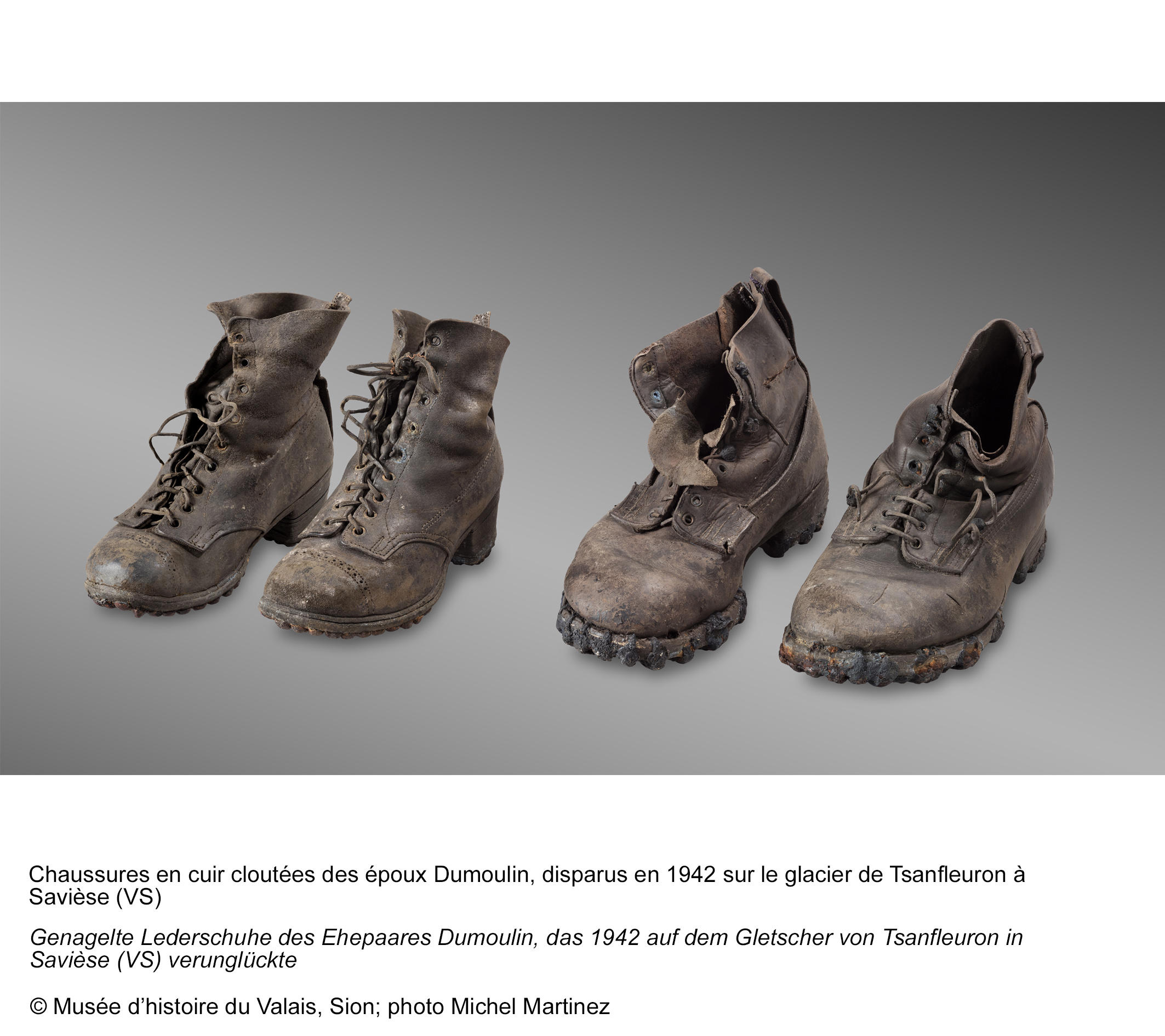

Among the poignant most recent vestiges are the heavy black boots that belonged to Marcelin Dumoulin and his wife Francine. The couple from Savièse, above Sion, disappeared on August 15, 1942 in bad weather while out tending to their cattle on an alpine pasture. They left behind seven young children.

Seventy-five years on, a lift worker found their icy remains, as well as their rucksack, watch, a prayer book and bottle on the surface of the Tsanfleuron GlacierExternal link above the village of Les Diablerets. Since 1960, the ice sheet has retreated by roughly half a kilometre and shrunk considerably. On July 22, 2017 a funeral was held for the Dumoulin couple, attended by two of their children, grand- and great-grandchildren.

It is not unusual for people to disappear in bad weather on hazardous glaciers. How many remain trapped under the thick ice? Nobody knows. Since 1926, some 300 people have disappeared and are officially unaccounted for in Valais alone, the Swiss canton which boasts some of the Alps tallest peaks and is highly glaciated.

But as Swiss glaciers thin and recede, mummified bodies and rare archaeological objects trapped in the ice are frequently emerging. And the phenomenon may accelerate. Scientists warn that almost all the ice sheets in the Swiss Alps could disappear by 2090 due to climate change.

Only this month, Valais police confirmed that the bones and climbing equipment found in September at the base of the Matterhorn belonged to a Japanese mountaineer who had disappeared four years ago. It said the bones had become visible as the thick snow and ice had melted.

In 2012, the skeletons and equipment of Johann, Cletus, and Fidelis Ebener turned up on the Aletsch glacier, 86 years after they vanished. A hiking boot that belonged to one of the Ebener brothers sits in a glass museum case, alongside a Neolithic moccasin that has also been spat out by a glacier.

The exhibition also features the personal belongings of the “Théodule Pass mercenary”, an unidentified man thought to have fallen into a crevasse above Zermatt in the 17th century with his sword, pistol, daggers and bags. His bones, clothing, money, and other personal items were recovered by a Zermatt couple in 1984 on the glacier. Detailed research later found that the “mercenary” was most probably a wealthy trader travelling from Italy to Switzerland, and possibly on to Germany, through the busy mountain pass.

“What’s interesting is not his sword or dagger but his shoehorn,” said Nicod. “It’s one of the oldest iron shoehorns, perfectly dated. And things like his personal pocket knives and amulets give us a much more intimate picture of him.”

“I think it’s the nature of the objects,” he says of the public’s fascination with such discoveries, as well as the macabre and adventurous aspects. “What are these things doing up there at 3,000 metres above sea level?”

He likens each well-preserved object as a “photo” of the past, helping our understanding of human movements over numerous mountain passes over the centuries, as well as about clothing, equipment, hunting techniques and the exploitation of natural resources.

The exhibition also features a collection of rare objects – a shoe fragment, a bow and arrows, an arrow case and leg coverings – that belonged to a hunter from the Neolithic period (2,800 BC). His possessions – but no bones – were discovered by a Swiss hiker, German climbers and Bern archaeologists – at the Schnidejoch pass north of Sion, between 2003-2004.

The climbers who found the bow took it back home to Germany, and only decided to contact the Valais archaeological service to hand it over three years later.

Nicod recounts a similar story about a 5,800-year-old snow shoe, made of wood and strips of willow, which was discovered in the province of Bolzano in northeast Italy.

“It was picked up by an Italian engineer who was working on the border between Austria and Italy. He took it back to his office, where it spent 7-8 years in a cupboard before he decided to show it to archaeologists,” he explains. “Many interesting finds only emerge a few years on. It’s a shame, as they can get easily damaged.”

Once exposed to air the extremely fragile objects degrade rapidly. Therefore, it is important for specialists to be able to collect and store them in a controlled cold environment.

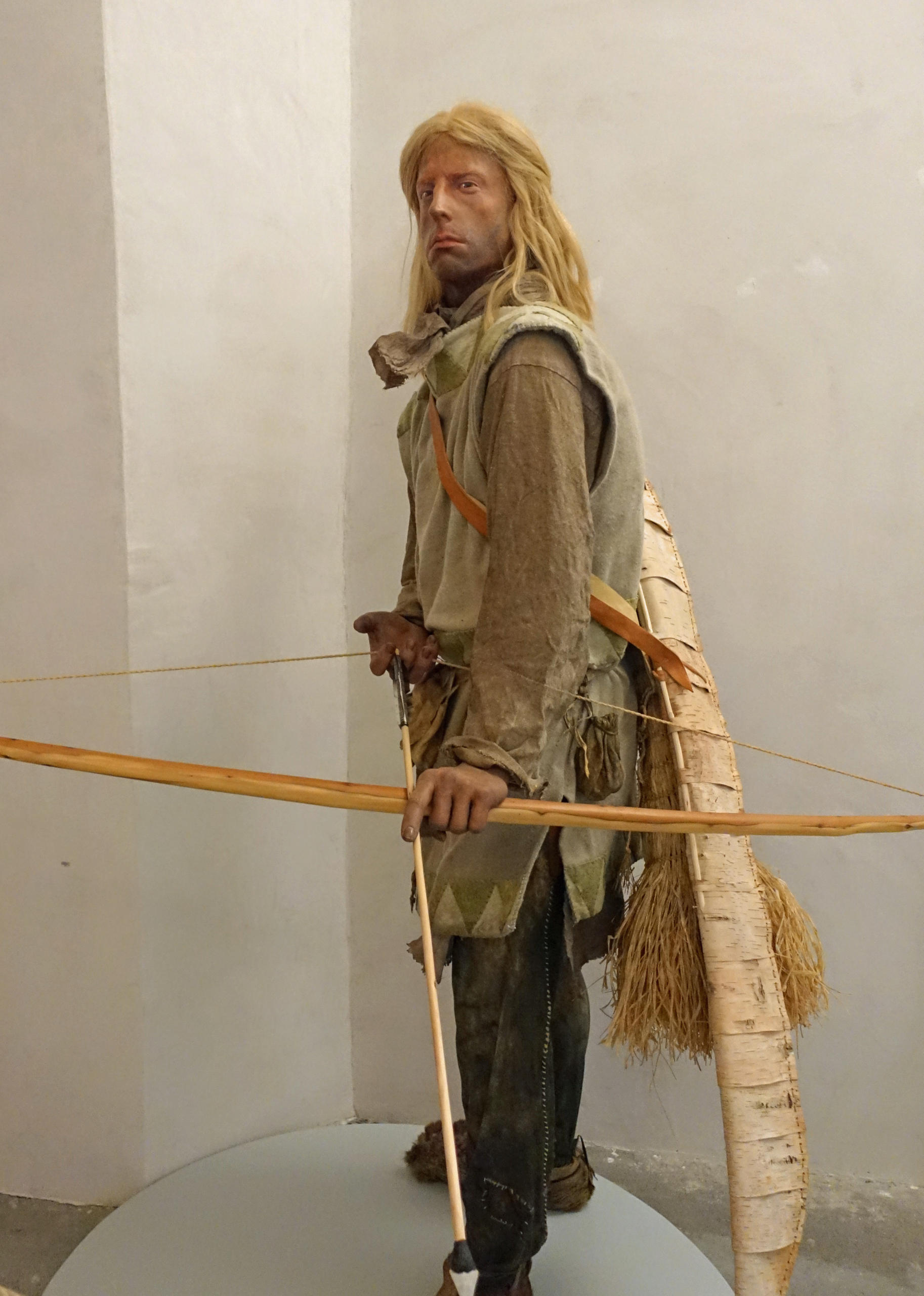

Glacial archaeology remains a relatively new discipline, despite gaining a massive boost in 1991 with the discovery of Ötzi, the 5,300-year-old mummified man who was found in a glacier in the Alps, between what is now Austria and Italy.

Nonetheless, it has developed considerably over the past 30 years in Switzerland, becoming more professional and specialised. Canton Bern, for example, has developed a centre of expertise and every summer a team of archaeologists spends weeks collecting material and preserving objects.

Canton Valais has similar plans; it has created an interdisciplinary working group to see how to develop its glacial archaeology work. One idea is a smartphone app for the public to be able to send in information about interesting objects they stumble across when out on a glacier.

“The problem is that we need to do it quickly, as Valais has 30% of all Alpine ice and the glaciers are melting fast,” Nicod warns.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.