Despite criticism, Switzerland continues to incarcerate minors

Each year, around 20 minors are locked up in Swiss prisons for various lengths of time. Their requests for asylum having been rejected, the authorities place them in detention before their expulsion from the country. Despite strong criticism, the Swiss parliament refuses to ban the practice.

Switzerland is one of 196 countries which has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the ChildExternal link, which stipulates that the detention of a minor must only be used as a last resort and for the shortest amount of time possible. However, each year, around 20 children are locked up in different prisons around the country.

In 2017 and 2018, 37 minors were placed in detention in Switzerland for periods of two to 120 days, according to the latest report from the National Commission for the Prevention of Torture (NCPT)External link. They were asylum seekers aged between 15 and 18. Their demand for asylum having been rejected, they were imprisoned while waiting to be expelled from Switzerland. This so-called “administrative detention” is regularly used in Switzerland with adult asylum seekers whose requests were unsuccessful, but the NCPT was unequivocal in its conclusion that it’s inappropriate for children.

“In the context of migration, the detention of minors, whether they are accompanied or not by an adult, is judged to be inadmissible in view of the best interests of the child, which must take precedence over immigration status,” the report stated.

The NCPT discovered that three cantons had placed minors younger than 15 in detention with their families, even though Swiss law clearly forbids it. This process was strongly condemned last year by a committee within Swiss parliament, which had discovered that the majority of the 200 children in administrative detention between 2011 and 2014 were younger than 15. The government responded in November 2018 by demanding the cantons put an end to the practice.

More

What prison is like for failed asylum seekers

Detention of minors strongly denounced

“Switzerland does not treat these children as children, but first and foremost as migrants,” says Tanya Norton, who works for the children’s aid organisation Terre des Hommes (TDH). TDH was one of the first NGOs to denounce the imprisonment of minors in Switzerland in a report it published in 2016. Several associations followed suit and called for a ban on the detention of minors. The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights recommended in 2017 that Switzerland stop detaining people under the age of 18.

TDH also points out the lack of reliable statistics on the imprisonment of child migrants in Switzerland. This is explained by sometimes significant differences between data provided by the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) and data transmitted directly by the cantons responsible for deporting asylum seekers. The SEM puts the discrepancies down to errors in data collection by the cantons, which it says should by now have been corrected.

No common policy under federalism

“What is unbearable is that this gives the impression that children are not important,” says Norton. Especially since the way in which children are treated can change completely depending on which canton is responsible for sending them back. In Geneva and Neuchâtel, for example, no minor can be placed in administrative detention because the practice is prohibited by cantonal law. Most cantons have stopped detaining migrant minors in recent years, but ten cantons resorted to the practice between 2017 and 2018. There, the rates of detention varied greatly: Basel City and Bern, for example, both detained 11 asylum seekers aged 15 to 18, although Solothurn only detained two, and Glarus one.

“We want a national law and controls at the federal level,” says Norton. “The state must be responsible for implementing international treaties, it should not be relegated to the cantons.”

As noted by the NCPT in its recent report, the sole objective of administrative detention is the guarantee of sending back a person who does not have the right to stay in Switzerland. Since it’s not detention meant for punishment, the incarceration regime should reflect that and be a lot more relaxed than at a penal institution. Numerous cantons have decided to modify their practices in recent years and find alternatives to pre-deportation detention that is less traumatising, also for adults.

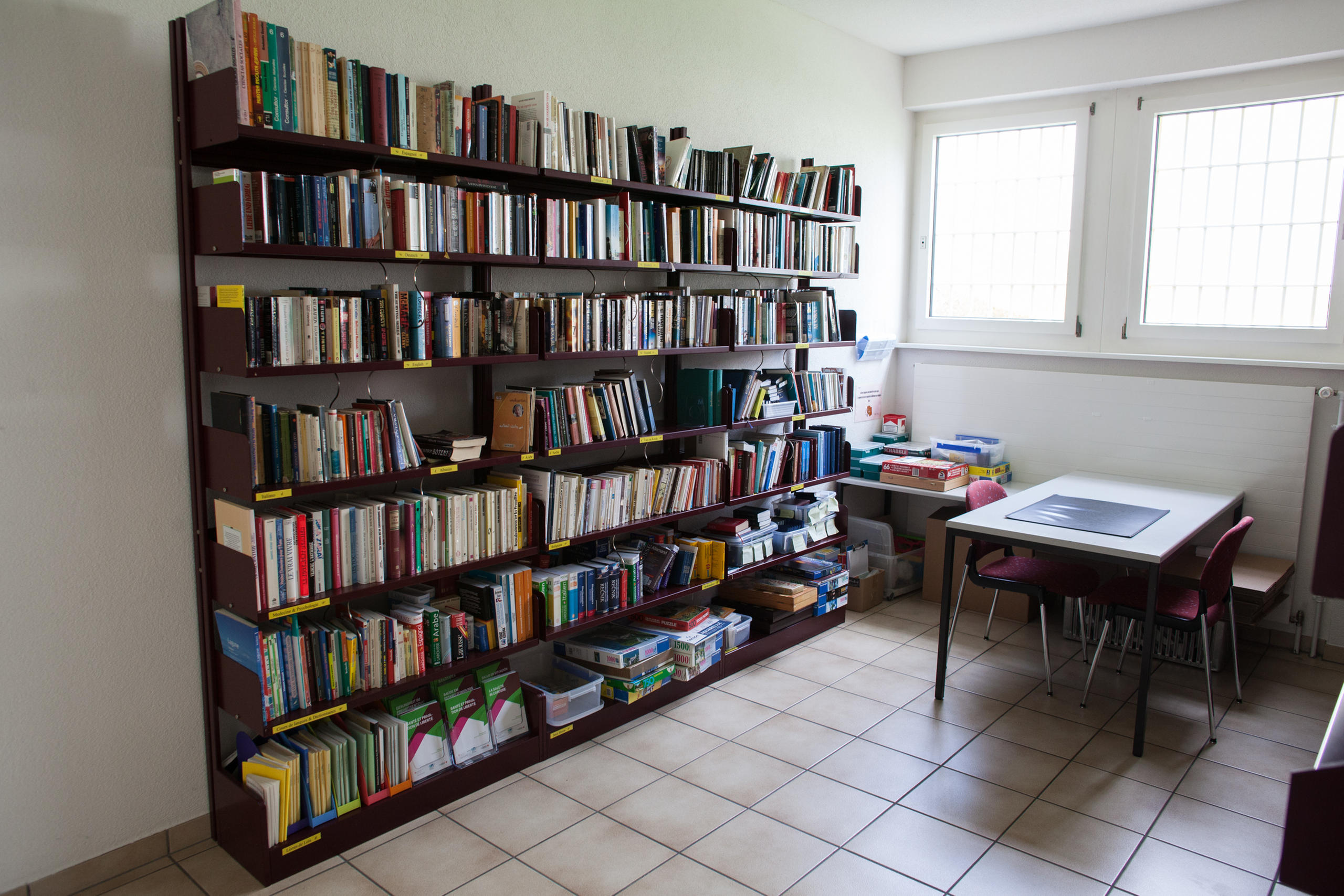

A new approach to detention at Moutier

For example, canton Bern modified its entire penitentiary organisation in July 2018, deciding to convert one prison in the Jura region into an institution primarily used for administrative detention.

“It was really a paradigm shift for the personnel and the institution,” says Andreas Vetsch, co-director of the prison in the town of Moutier.

At the new facility, all detainees can move freely during the afternoon between two floors of the building, and on the roof. They can read, play sports, work and do other activities.

“We want to concentrate less on the security and more on a form of support,” explains Vetsch. “We want to find the right path between respect for our laws and the maximum human rights for people who are detained.”

In 2019, only one minor has so far been detained at the Moutier facility.

Changing mentalities

Switzerland is not the only country to make extensive use of detention before deportation of failed asylum seekers, including children. A global study by the UNExternal link on the subject, published in July, revealed that at least 330,000 children are detained each year in the context of migration, in at least 77 countries. The practice is widespread in the European Union, although data is difficult to obtain.

But the mindset is changing. In December 2018, 164 countries adopted a Global Compact for MigrationExternal link which reaffirmed the international commitment to combat the detention of children. Switzerland was one of the mainstays of the project, but its adhesion has been delayed due to scepticism on the part of parliament which demanded a say on the subject.

“Switzerland is one of the few countries which remains very restrictive with the detention of minors,” notes Norton. “It’s very surprising, because Switzerland had sent signals that it was advancing its policies, but the intentions were not reflected in the facts.”

This year, Swiss parliament rejected two proposals calling for a ban on the administrative detention of minors. Its view is that the possibility is only used as a last resort, when no other solution has been found, and that it is indispensable for enabling the cantons to carry out deportations.

The incarceration of a child, even for a short time, nonetheless has serious consequences, according to the UN study.

“Administrative detention harms the physical and mental health of children and exposes them to risks of violence and sexual exploitation. It has been shown that it aggravates or brings to the fore health problems, notably anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts and post-traumatic stress,” the study says.

Rising rate of disappearances

The fear of finding themselves in prison also leads to several children running away, warns TDH.

“They become even more vulnerable and at risk of winding up in the European networks of sexual or worker exploitation,” says Norton.

The SEM, for its part, believes that the aim of administrative detention is to avoid the disappearance or the non-controlled departure of a person. It says that minors who lodge a demand for asylum in Switzerland are registered and “may be subject to specific protection measures and searches” if they disappear and are found again.

With the implementation of the new asylum procedure this March, individuals under the age of 18 are given legal representation immediately upon lodging their asylum request.

The SEM argues that this measure ensures better protection of unaccompanied minors.

Numerous associations nonetheless call the increase in disappearances of young asylum seekers since 2015 alarming. They denounce the lack of reliable data on the trend.

The SEM reports the number of “non-controlled” departures, without specifying if the people in question disappeared, exited the asylum system, left Swiss territory or went into hiding. Non-governmental organisations denounce the absence of a systematic mechanism for signalling these disappearances and the lack of resources deployed for finding these children.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.