Radioactivity still shows up in Switzerland

Thirty years after the Soviet nuclear disaster, traces of radioactive elements from Chernobyl are still being registered in Switzerland, especially south of the Alps in Ticino. Are these contaminants still a risk to public health?

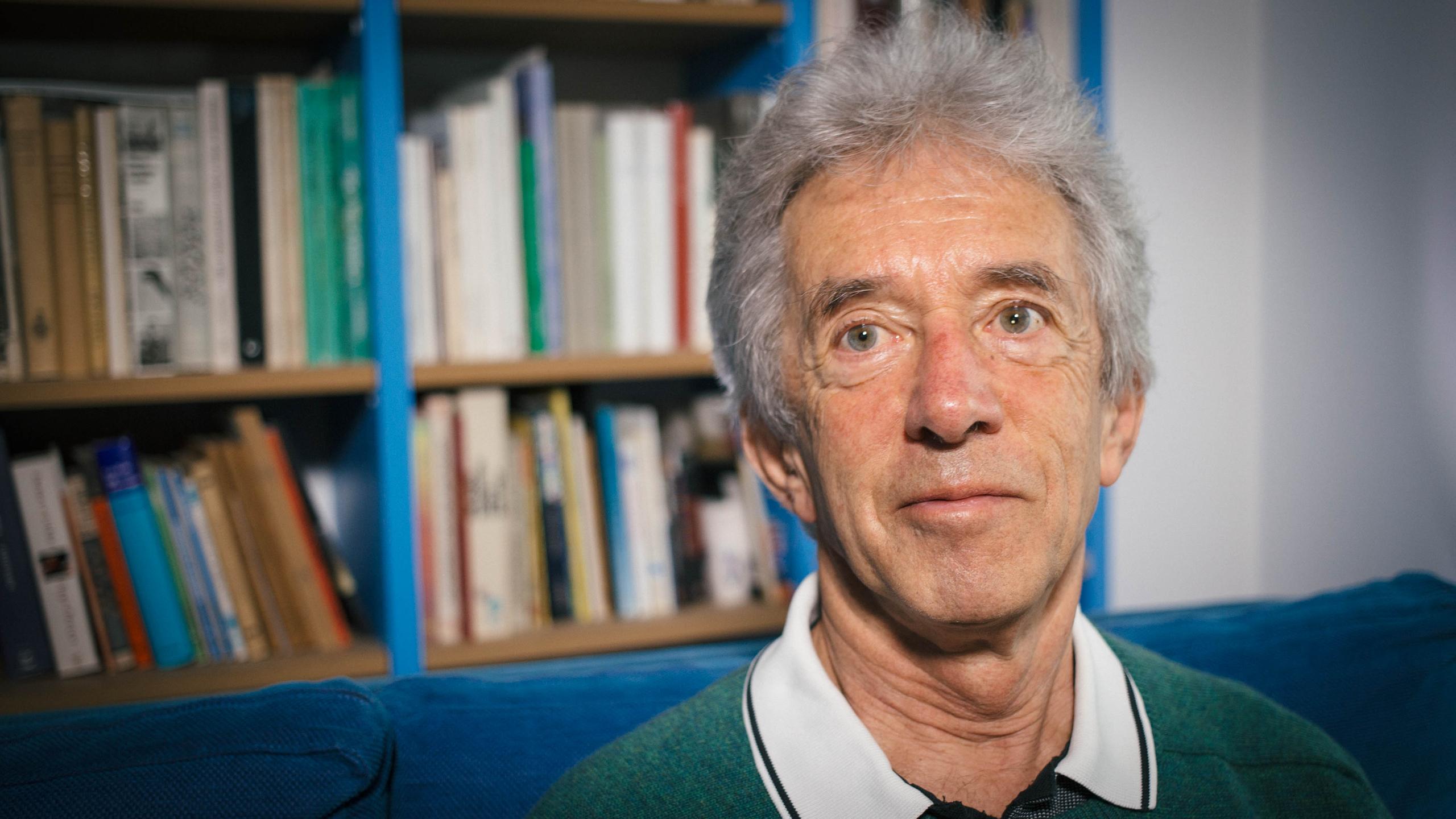

“Memories fade quicker than caesium-137,” which has a half-life of 30 years, says Christophe Murith, head of the radiological risk section of the Federal Office of Public Health. Yet the momentous events of spring 1986 are still vivid in his own memory. He was in the front line when the poisonous cloud from Chernobyl reached northern and central Europe and Switzerland.

“It was the Swedes who warned us: they had noticed an anomalous spike in radioactivity,” recalls Murith, who at the time worked for the laboratory of the Federal Commission for Radiological Protection.

“I had just finished my thesis and I was experimenting with a technique of spectroscopy. All of a sudden I found myself doing real measurements out in the field, caught between locals who kept looking mistrustfully at me and federal officials who wanted as many readings as I could get.”

Using a truck borrowed from the Swiss army, the young scientist travelled through every valley in Ticino, the southern region of Switzerland most affected. The radioactivity was deposited wherever it had rained during the passage of the contaminated cloud.

“In Ticino, the reading of caesium-137 on the ground was 100 times the readings on the central plateau,” he said.

The priority was to protect those people most vulnerable to radiation, namely children and pregnant women. “The analyses focused on foodstuffs: we wanted to prevent contamination through food.”

A whole series of recommendations was issued by the government, which included not drinking fresh milk and washing salads and greens thoroughly.

More

An exaggerated reaction to a real threat

All in all, the average dose of radioactivity to which the Swiss population was exposed in the aftermath of the Chernobyl disaster was fairly limited. According to government estimates, it was 0.5 millisieverts (mSv) a year. In comparison, the dose associated with a normal x-ray is 1 mSv.

“People who didn’t follow the recommendations could have received a dose ten times greater,” Murith said.

Persistent traces

Thirty years on, the traces of the nuclear catastrophe are still out there in the Swiss environment. In Ticino and in some valleys in Graubünden in eastern Switzerland there is still caesium-137 attributable to Chernobyl, he says.

“The caesium persists mostly in the higher strata of the forest ecosystem. It is accumulated in mushrooms and the bodies of game animals. Even today the concentration of caesium in wild boars can be over the threshold. In those cases the meat can’t be sold commercially.”

Swiss lakes also contain deposits caused by Chernobyl, as can be read in a recent report from the Federal Nuclear Safety Inspectorate, which cites a studyExternal link published in 2013.

In Lake Biel, one eighth of the caesium-137 deposited between 1950 and 2013 can be attributed to Chernobyl. The rest comes from nuclear testing in the 1960s and the Mühleberg atomic power station, according to the study.

No major increase in tumours

The presence of radioactive elements, picked up by very sensitive measuring devices, is of great interest to specialists in the field, says Bernard Michaud, former deputy director of the Federal Office of Public Health.

Yet “in terms of public health it has no ongoing repercussions. In Switzerland there has been no measurable increase in thyroid tumours [caused by exposure to iodine-131], malformations or other tumours”, he said.

It is, however, likely that people did get ill because of Chernobyl, Murith thinks. “Establishing a causal relationship is tricky, because thyroid tumours were on the increase anyway, especially in women.”

The documented increase, he points out, was mainly due to more sophisticated diagnostic systems.

The estimates from the Federal Office of Public Health, extrapolated from statistics gathered after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, are in terms of 200 additional deaths in Switzerland.

“This is very different from the situation in countries like Ukraine, Russia and Belarus, where there were at least 4,000-5,000 cases of thyroid tumours unquestionably due to Chernobyl”, Murith pointed out.

The Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Bern told swissinfo.ch there have been no apparent effects of Chernobyl on tumours in children either.

Ben Spycher, a child health specialist there, has reported in a recent co-authored studyExternal link that even fairly low doses of radioactivity – as occur naturally – may give rise to leukaemias and brain tumours in children.

“A minimal part of this naturally occurring radioactivity comes from Chernobyl. Even if there were a relationship with what happened in 1986, it would most likely be very minor,” he said.

Long-term effects

But Jacques BernierExternal link, head of radiation oncology at Genolier clinic in canton Vaud, notes that papillary carcinoma (a kind of thyroid tumour) in patients exposed to radiation reveals chromosome mutations that vary over time.

“So it’s best not to let down our guard”, he said. “Especially as these mutations can have long-term potential risks.”

The World Health Organization’s Agency for Research on CancerExternal link in Lyon says that effects of radiation may appear several decades after the initial exposure. For a complete evaluation of the health consequences of Chernobyl, it recommends putting a long-term research programme in place.

Murith is sure at least of one thing: “Depression, anxiety, suicide, post-traumatic stress and in general the lack of prospects for the population that was evacuated are still the main problems. The psychological after-effects of the catastrophe are much worse than the radiological ones.”

Fires still a risk

Following the Chernobyl nuclear accident, considerable quantities of hazardous radioactive material were deposited on forests and farmland near the power plant. These are likely to be released into the atmosphere due to frequent fires in the region, according to warnings from GreenpeaceExternal link.

An uncontrolled fire may be equivalent to a level 6 incident on the international scale of nuclear events (Chernobyl was level 7), says the environmental group. In 2010, radioactivity released by smoke from one fire spread as far as Turkey.

This aspect is “taken seriously”, the Federal Office of Public Health has told Swiss newspaper Le Matin Dimanche. If there were fires of a particular level of intensity, Switzerland would be quickly informed since it belongs to an international network, says the government department. If the worst came to the worst, the dose of caesium-137 that would come down in Switzerland would be 100 to 1,000 times lower than what was detected in the country in 1986.

Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.