Covid review: not all our predictions were wrong

One year into the pandemic, we still have so many questions. Here in Geneva, we can put those questions to world leaders in public health.

When can we get vaccinated? When can we meet friends again? When, oh when, will this virus give up?

It’s been interesting, reporting on Covid-19 over the last 12 months, to re-assess some of their answers one year on.

In this week’s episode of our podcast, Inside Geneva, I take a look back at interviews conducted almost exactly a year ago with the WHO’s Margaret Harris, and with Vinh Kim Nguyen, an emergency doctor with MSF who is also co-director of Geneva Graduate Institute’s Global Health Centre.

More

Covid-19: When hindsight is 20-20

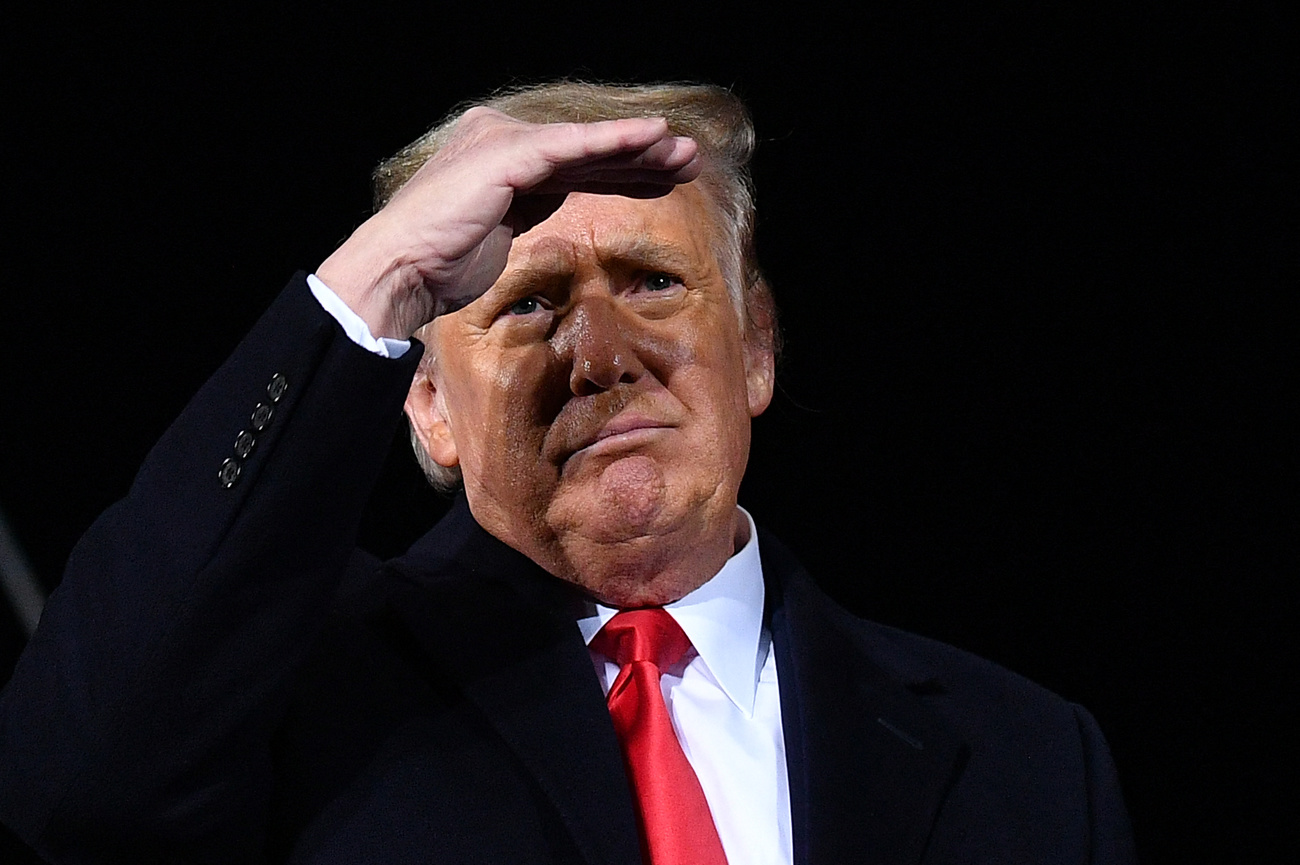

Listening to them again is quite eerie: Margaret Harris predicted that the WHO, as “the body there to protect public health” would also be “the body that is most likely to be scapegoated when everybody is facing a threat like this”. This was some time before Donald Trump announced the United States would leave the WHO, taking that $450 million contribution with it.

The US recommitment to the WHO was one of the talking points in the last Inside Geneva episode, when I was joined by journalists Tom Miles and Gunilla von Hall and Daniel Warner to discuss everything from Washington’s volte face new enthusiasm for multilateralism, to the prospects of the WHO mission to China, to the future of the UN in Geneva itself, now that so much diplomacy has gone virtual.

Returning to the interviews I conducted in early 2020, Vinh Kim Nguyen predicted a “crashing” of the global economy. That was at the start of the very first lockdown, which most of us fondly imagined would last a few weeks at worst. Even Margaret Harris told me at the time that she didn’t expect lockdowns to last “for months”. “Well, we got that wrong didn’t we,” she admitted last week.

Still, I’m impressed by how much they got right. This was a brand new virus, and it rapidly created a global pandemic the world simply wasn’t prepared for. The WHO, to be fair, had warned for years that a pandemic was inevitable, but governments, particularly in the austerity years after the 2008 financial crash, were disinclined to invest in something that seemed rather vague.

Suerie Moon, also a co-director of the Global Health Centre, knew that most countries were not ready. She and her colleagues who specialise in infectious disease outbreaks had gamed a pandemic, trying to anticipate all the challenges governments might face, from lack of supplies, to societal disruption. What they didn’t expect, she told Inside Geneva, was reluctance from some political leaders to mount a pandemic response at all.

“We did not foresee the idea that some governments would just give up, the idea that some governments would simply say I’m not going to try to contain this pandemic.”

To hear more about what we thought then about Covid-19, what we know now, and what lessons we may have learned, do tune in to Inside Geneva. One thing those interviews made me reflect on was just how much our lives have changed, in multiple small but incremental ways, since last year. Then, Vinh Kim Nguyen predicted a “new normal”, but said he didn’t know what normal would look like.

Now we know it means masks, and, so hard for us social creatures, avoiding human contact rather than seeking it out. It means endless hand washing. It means knee jerk irritation if someone gets too close in the supermarket. It means working from home, home schooling your kids. It means no foreign holidays, no museums, no theatre, no cinema, no restaurants, no crowded bars or boisterous football matches.

Sign up! The latest updates from International Geneva – in your inbox

But sometime, hopefully soon, that will change, and perhaps we should try to look on the bright side. The new normal also means multiple vaccines developed in record time, and an unprecedented cooperation between the WHO, scientists, pharmaceutical companies, and member states to create a facility, COVAX, to ensure low income countries get vaccines. It may not be working, yet, quite as well as the WHO hoped, but COVAX has gone further and faster in the field of fair access to medicines than any other programme in history.

I read a rather nice article this week pointing out that it’s good for us to stay positive, that it’s good for us to plan a holiday even though it may not actually take place this summer. I have a friend who has done just that – she’s planned a sailing break in Greece at the end of April. She may not be able to take it then, but it did her the world of good exploring routes, checking out harbours with nice tavernas, and researching bays with nice beaches.

But I also reflect, sometimes, on what aspects of our pre-pandemic life may be gone for good. Will we still shake hands when we greet people? Or give the Swiss two or three kisses on the cheek when meeting friends? Or will they be written up in someone’s social anthropology thesis, sometime in the 22nd century, as social habits which mysteriously disappeared in 2020?

These are more questions that we don’t have answers to. But we have learned things, over the past year. For one, that we are so much more adaptable than we could have predicted. We have coped with this for a year, and not gone completely insane. We have kept working, restaurants have stoically turned into takeaways, teachers and professors have developed brilliant distance learning techniques, we have all become experts with Zoom. (Did you know it has a facility to “touch up your appearance”?)

So perhaps, despite this grim, long winter, we should celebrate our sheer determination to keep going, and keep reminding ourselves, as that article I read said, that “hope is good for us.”

Let’s see what we’re doing this time next year.

More

How is International Geneva shaping up?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.