How much tech should be in Swiss classrooms?

Where pupils once sat at their desks with the teacher at the blackboard, they might now be putting together a video essay or learning to code a robot. Education is undergoing a sea change, but not everyone in Switzerland feels ready for it.

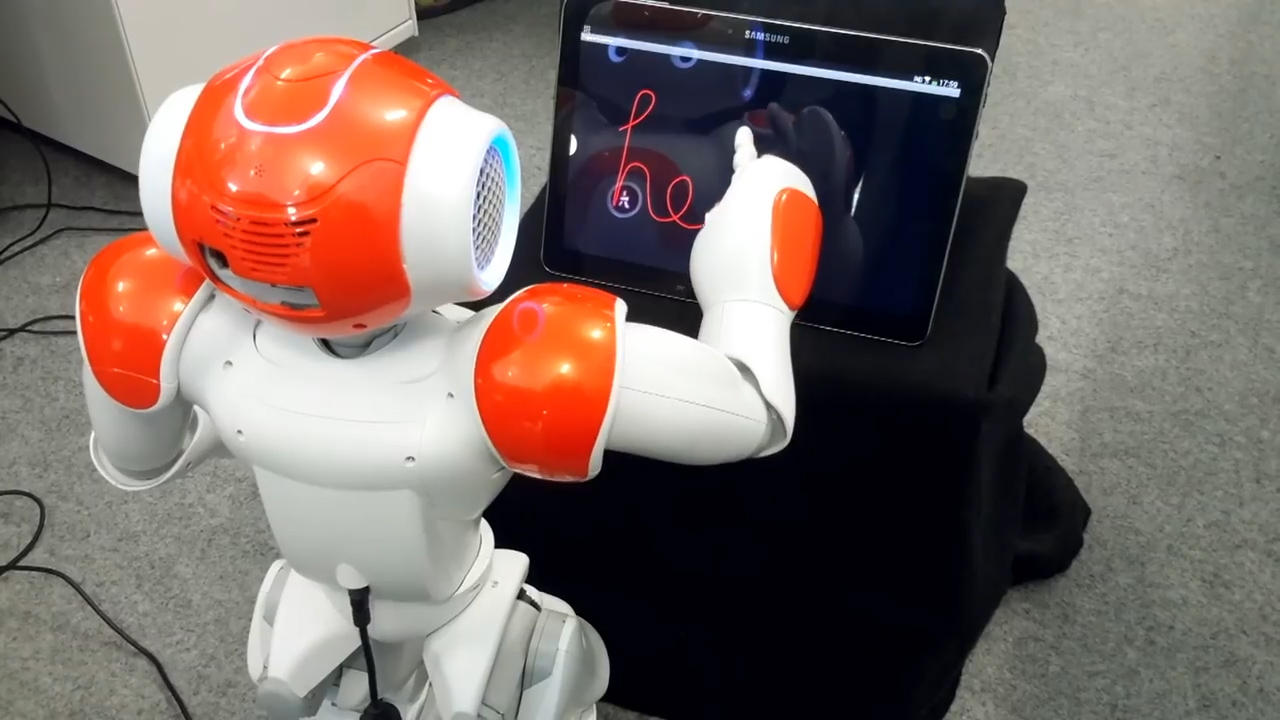

Digitalisation – the move from analogue to digital technology – was a big buzzword at the recent WorlddidacExternal link and SwissdidacExternal link fairs on educational trends held in Bern. There were many digital learning technologies on display, including this Finnish language-learning robot.

More

Elias: the robot who’ll try your favourite food

In Switzerland, digital learning technologies have been used in classrooms for some time, but it has only recently become a big public issue, said Beat A. Schwendimann of German-speaking Switzerland’s Federation of Swiss TeachersExternal link (LCH).

Over the last year, the Swiss government has released its digitalisation strategyExternal link and the cantons – which are in charge of education in Switzerland – have published their blueprint for schoolsExternal link.

“Things are moving forward in Switzerland,” Schwendimann says regarding educational technology.

‘Learning first, technology second’

Joseph SouthExternal link is the chief learning officer at the United States-based International Society for Technology and EducationExternal link (ISTE), which held the “Transforming EducationExternal link” conference at Worlddidac. The former director of the Office of Educational Technology at the US Department of Education says this is the moment when educators need to be thinking through the right strategy for digitalisation, since it’s “impacting every part of the education system”.

South says the priority should be on “learning first and technology second”.

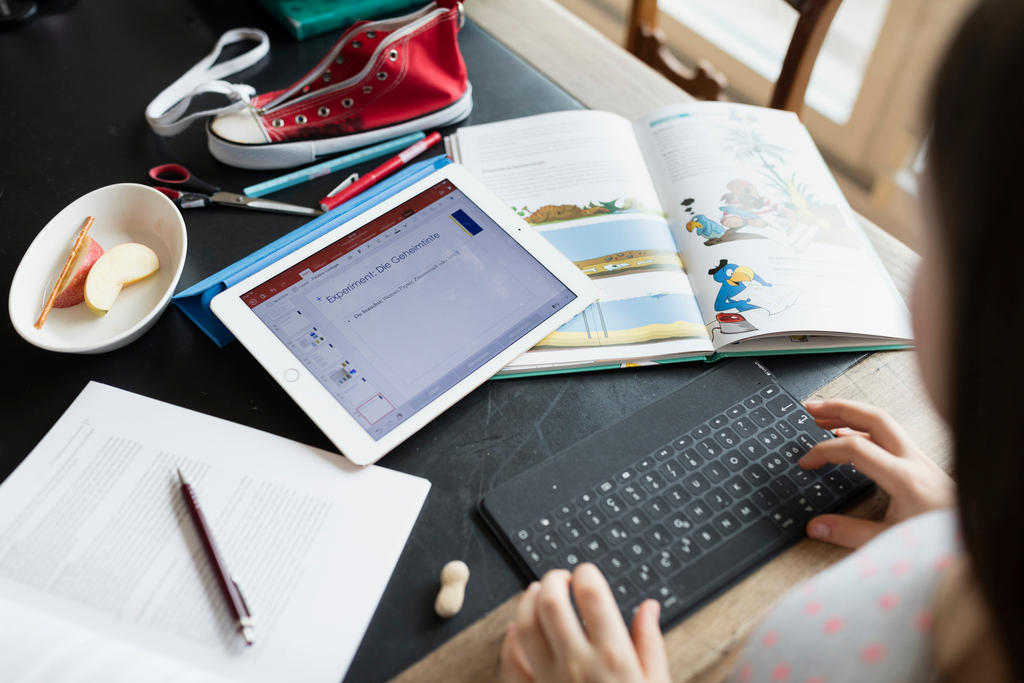

“When you do school tours, iPads are everywhere, but that doesn’t actually change learning,” he explains. “You can do things just as right or just as wrong as you were before, with or without an iPad.”

Technology needs to be a transformational experience for learning, emphasises South, whose organisation has developed standardsExternal link for using tech in the classroom.

Effects on pupils

But there are still some concerns over the effects of tech on pupils, even in the US where digital learning technology has been in use for some time. South points out that using a device to communicate or problem solve, for example, is different from just passively watching and listening.

“Part of the reason there is a slow uptake in some places is that we’re don’t trust tech, we’re not sure that it’s going to be better for us,” he says. “We’re right to be wary, as it can be used in a way that isn’t helpful. But the upside, the possibilities for transformation, are so great that we really do need to embrace it.”

Students also need to learn how to be good digital citizens, he adds. This means learning when to use technology, how to use it civilly, and how to use it to bring about change

“If this is done, a lot of our concerns about technology will go away,” South argues.

Teachers’ concerns

In Switzerland, the teachers’ federation (LCH), along with its French-speaking counterpart SER, recently set down a similar viewpoint to South’s in a position paperExternal link on educational technology.

“We call it ‘pedagogy before technology’,” says Schwendimann, adding that key is to ensure that “tech really adds value to education. It’s not just the number of digital devices in the classroom that counts, but how they are being used”.

For this, Schwendimann and his colleagues argue, teachers need proper training and innovative text books.

But he admits that some teachers, curious as they are about learning and developing professionally, are anxious about the introduction of new technologies. Teachers are rightfully cautious about claims by edtech companies, he says. They need reliable curriculum activities, for which they need to be trained.

Schwendimann notes that all too often, politicians allocate one-time budgets for hardware but then expect teachers to muddle through using it on their own.

And the goal is not to have technology everywhere and all the time, he emphasises. “Teachers need to use their professional judgement to decide when to use digital technologies in the classroom, and when not to use digital technologies.”

Nevertheless, a mandatory Media and InformaticsExternal link module has been introduced at the primary-school level under the new unified Lehrplan 21External link curriculum being phased into German-speaking Switzerland. Similarly, the curriculum in the French-speaking partExternal link includes media and informatics (MITIC)External link as a cross-subject topic.

+Read here why IT is also mandatory at upper secondary schools

These courses are designed to help prepare students for the digital world, Schwendimann says.

Computational Thinking

ISTE’s Joseph South was impressed by one area of educational technology in which Switzerland seems to be ahead of the curve: its emphasis on computational thinking, or the breaking down of a problem so that a machine can execute it.

For example, a Computational Thinking Initiative (CTI)External link for education, supported by the teachers’ federation (LCH), was launched during the nationwide Digital Day on October 25. It uses the robot “Thymio” to teach these skills to primary school pupils. The technology was developed by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL).

More

New centre adds computational thinking to school curricula

To Schwendimann, schools are facing two challenges: the use of technology as teaching tools, and how to teach about technology as content (such as fake news or social media).

Overall, he concludes, Switzerland is doing well at dealing with technology in education, but there is more to be done to compete with countries in Scandinavia or Estonia, South Korea and Singapore. The German federal government has also released €5 billion (CHF5.7 billion) to further develop ICTExternal link in public schools.

“It requires a concerted effort from the federal government, right down to schools,” Schwendimann said.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.