Foreign children forced to grow up ‘in the closet’ call for apology

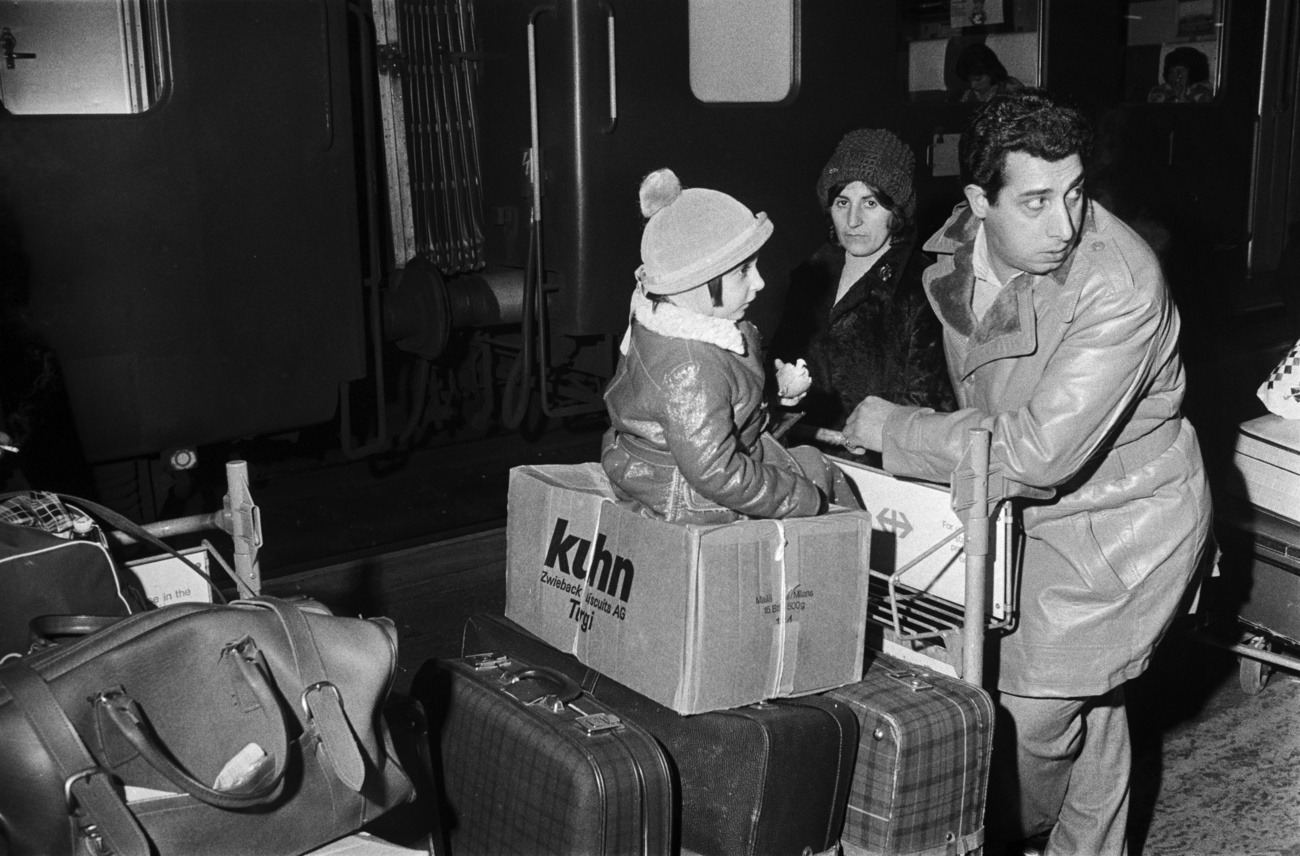

For many years thousands of children of seasonal workers could not live in Switzerland with their parents, or had to do so illegally. This has left its mark on many families. Now an association is campaigning for redress from the government.

“This story didn’t happen in the Middle Ages or in some distant country, but in Switzerland, the homeland of the Red Cross. It was an attack on the integrity of the family, and no one at that time raised their voice in protest.” This was the opening statement from Egidio Stigliano, vice-president of the Tesoro association, which was officially inaugurated on October 1 in Zurich.

The group is demanding an official apology from the Swiss authorities and compensation, even a symbolic amount, for the victims of the seasonal workers programme.

What exactly is meant here? Seasonal work has existed throughout history. For a certain period, however, a foreign worker status existed in Switzerland. Created by federal legislation on residency for foreign citizens in 1931, this programme belonged to “an overall migration policy intended to ensure the necessary flexibility for the needs of the economy and at the same time to discourage mass immigration”, according to the Historical Dictionary of SwitzerlandExternal link.

The Swiss economy in fact profited considerably from this programme. For example, it enabled it to deal with the repercussions of the oil crisis in the 1970s. The crisis was in a sense exported – simply by means of a drastic reduction of these work contracts, as can be seen in the chart below.

‘Illegal’ children

What did this work permit actually involve? Seasonal workers could reside no more than nine months of the year in Switzerland, they had a right only to limited benefits as regards social insurance, and they couldn’t change jobs during the season.

Also, family reunification was not allowed. In other words, people who came to Switzerland “for the season”, in particular in the hospitality and building sectors, could not bring their families with them. If both spouses had seasonal permits, they had to leave their children at home.

Although some improvements were made (for example, in 1964 Italy obtained the concession that after five consecutive seasons seasonal permits became annual authorisations, which gave the right to family reunification), this situation went on until 2002, when seasonal status was abolished with the introduction of free movement of people between Switzerland and the EU.

Whereas the Swiss economy benefited from the seasonal workers, the kind of status forced upon them marked many families for life.

Many people had to be away from their children for long periods. However, many others smuggled them into Switzerland illegally. These children had to be kept out of sight, to avoid being detected and possibly deported by the authorities.

Waving to a train

This is a situation that Egidio Stigliano, now 61 and a neuropedagogical therapist in canton St Gallen, eastern Switzerland, experienced first-hand as a child.

Stigliano’s parents left their native region of Basilicata in southern Italy in 1963, when he was three years old. On the day they left, he was taken out into the countryside by his grandmother, into whose care he had been entrusted, to wave at a passing train. At the time he didn’t realise that his parents were on the train, bound for Switzerland. Today his voice still vibrates with emotion when he thinks of the pain of the young mother and father watching their child recede in the distance, not knowing when they would see him again.

When he was seven, his grandmother died of a stroke. His parents decided to defy the law and take him to Switzerland. Once they got to Altstätten, in St Gallen, the rules of the game were brought home to him. “They told me: child, you have to stay home all day, and if you want to go out and play, you have to go out the back way and play in the woods,” he recalls.

“That wood became my home in a way, because I spent whole days there, alone. Then whenever I heard a siren, I’d go and hide in a hole I’d made for myself, thinking that no one would ever find me there. I always thought there was someone coming to take me away from my mother.”

Life in the shadows

There were thousands of other boys and girls like Stigliano, who, particularly in the Sixties and Seventies, were forced to live in the closet, as they used to say. They were like ghosts. There are no official figures, but some estimates say there were 15,000 in the Seventies alone.

More

The Italian seasonal workers in Switzerland

“What I remember most is the fear,” Stigliano says today.

One day, when he saw a school group in the wood, he decided not to hide any more, “because the desire to be with other children just got too much for me” and because they “could always play out in the sun and I always had to stay in the shadows”.

A lady came up to him and spoke to him in Italian – “maybe because I wasn’t fair-haired”. She asked him his name and what he was doing there.

“She was a schoolteacher. She went back into the village and reported the matter, just intending to get me into school,” he explains.

A few hours later, however, police were knocking on the door, saying the child had to go back to Italy. But his father’s employer intervened, vouching for him and convincing the authorities to allow Stigliano to stay with his parents and even go to school. “Capitalism won the day,” he recalls with a hint of sarcasm.

Raising awareness

But the wounds have remained, re-emerging during encounters, sometimes chance encounters, with other people who share this past. Thus was born the idea for the Tesoro association.

“It’s not a vendetta or anything like that. What we want is to get everybody to reflect a bit on this – also in relation to current events, seeing how immigrants are treated in many countries – and in a particular way Swiss politicians, so that something like that can never happen again,” he explains.

Apart from an apology from the federal government, the association is asking for compensation for the victims. It would just be “symbolic”, Stigliano emphasises. “Personally, I wouldn’t even use this word [compensation]. It could be just one franc. It’s an aspect we’re not too concerned about.”

The goal is really to raise awareness, as has happened in the case of the “Slave Children”, the child orphans and wards who were indentured to farmers until the 1960s in Switzerland.

More

Government apologises to child labourers

Stigliano aims to get the trauma recognised, also because not all the children involved got through the experience unscarred, he says. And not least, to stimulate historical research about those years, which apart from the odd study like Marina Frigerio’s 2012 book Forbidden Children has not dealt with the topic very much.

Parliamentary question

However, the issue will soon get an airing in parliament. It has been taken up by Samira Marti from the Social Democratic Party.

“We need to reassess this whole issue of criminalising the children of seasonal workers – in terms of public opinion, politics and history,” she says. “There also needs to be acknowledgement and some kind of symbolic amends made for what was a violation of human rights.”

During the winter parliamentary session Marti intends to request a statement on the matter from the government. “Then we will see what steps can be taken, in consultation with the Tesoro association.”

Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!