How the world’s countries provide public media

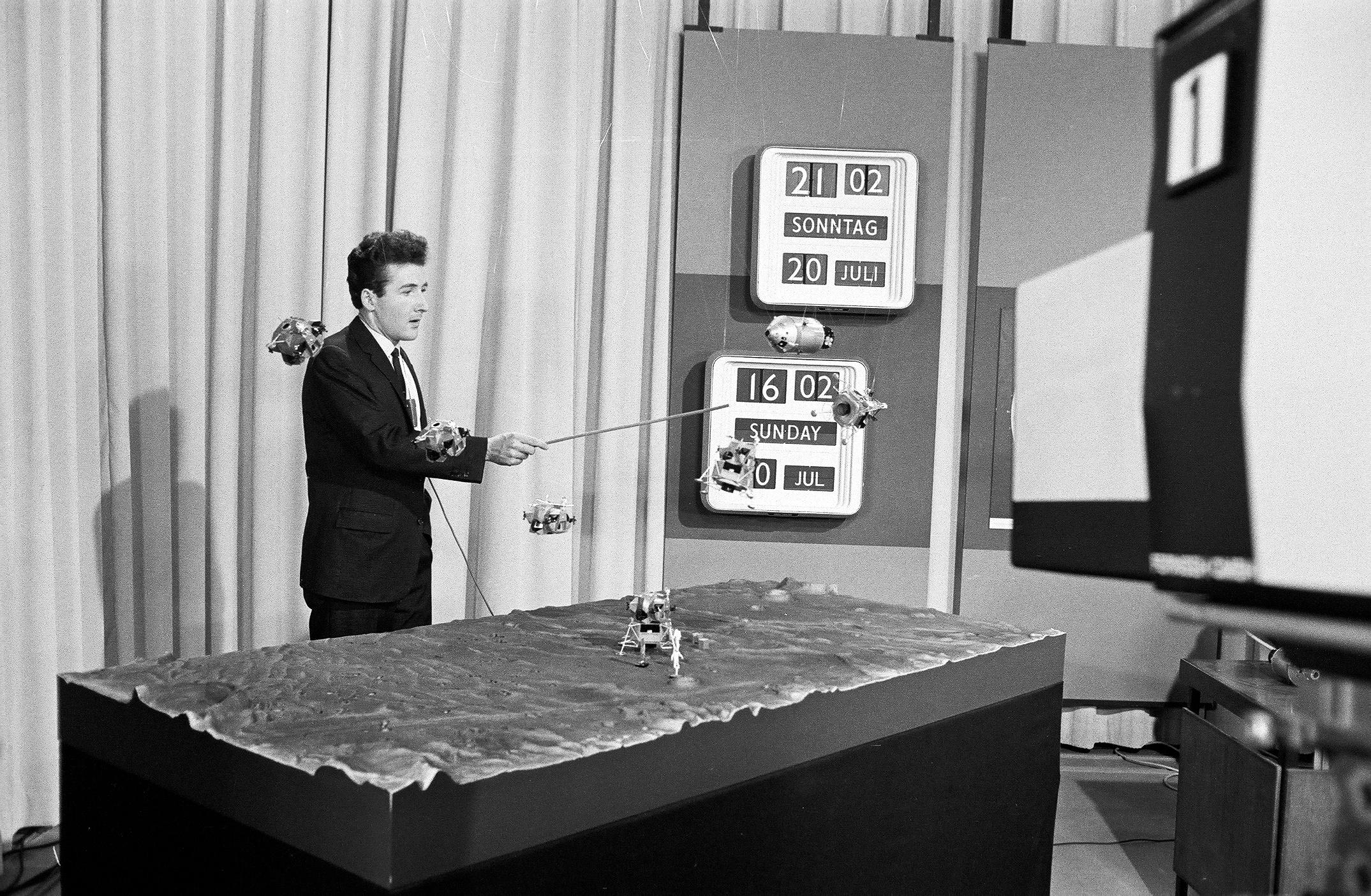

On March 4, Switzerland will decide on the future of its public service radio and TV. If voters turn out in favour of abolishing the licence fees that finance public broadcasters, the Swiss media scene will change drastically. What’s the situation for public media around the world?

SWI swissinfo.ch tapped its international network to find out what kinds of media systems exist elsewhere and how they are maintained.

Switzerland’s federal government should stay out of the media altogether. So say those promoting the “No Billag” initiative. The initiative text reads, “(The federal government) funds no radio or TV stations… The federal government (or third parties acting on its behalf) may not charge licence fees… The federal government does not run any radio or TV stations of its own in peacetime.”

There is no alternative. That is the official view of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation, of which SWI swissinfo.ch is a part, if the “No Billag” initiative is accepted by the people.

Because up to three quarters of the national broadcaster’s total costs are funded by the licence fee, it “would have to liquidate” if the vote passes on March 4, according to its executives.

A recent survey carried out by the polling institute Gfs.bern and the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation shows 60% of voters opposed to the initiative, 38% in favour and 2% undecided.

If the initiative passes, Switzerland would be the first country in Europe to abolish public service broadcasting, which has been around for decades on much of the continent. But if they didn’t already exist, would public media outlets still be brought about today?

The answer depends on each country’s political culture. In Russia, for example, our correspondent reports that few would be prepared to pay fees for public media. Currently, the Russian state exercises detailed control over what the media may or may not report on, with even private-sector media in the country requiring de facto state approval.

It is also striking that the online foreign platform “Russia Today”, which is close to the Kremlin, has invested hundreds of millions of Euro in strengthening its presence outside the country, notably in German and France. In France alone, the portal has spent €25 million.

Censorship and control

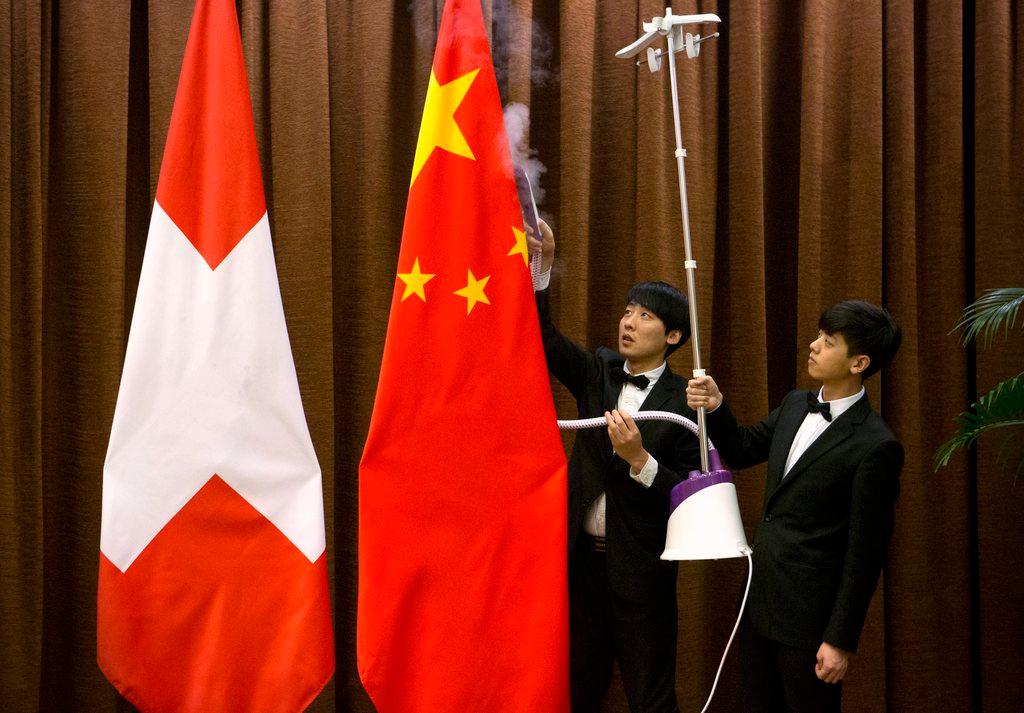

Censorship is the extreme example of state control, and swissinfo.ch has itself been on the receiving end in China where there are no public service broadcasters in the Western sense. The Chinese swissinfo.ch site has experienced temporary blockages several times, especially when our writers reported on thorny political topics such as direct democracy.

But just because a country does not have a public media system does not mean the state is automatically in conrol of the airwaves. In Brazil, for example, a small number of oligarchs dominate the media (the official TV Brasil carries little weight). The Globo company, which leads the market, hires the best journalists in the country, but there is no obligation for it to keep doing so.

Who pays?

In countries that fund public media through a fee from the public, the question arises of who needs to pay that fee. In Switzerland, the payment requirement was extended by a close popular vote in 2015. Currently, all households must pay the radio and TV licence fee, no longer just those who have the necessary equipment. This means inspectors are no longer needed to check whether people have a radio, TV or computer.

And how do overseers make sure the fees are actually being paid? In Japan, only 70 to 80% of people pay. This makes quite a difference in the budgets of Japanese public broadcasters, as they are not allowed to carry advertising.

The United States has a long tradition of purely commercial broadcasting, with state support for media only arising in the 1960s. American public media does not depend on a licence fee, but on direct federal government funding to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CBP). This independent agency, in turn, funds part of the budgets of public media stations such as local PBS (television) and NPR (radio) affiliates. This system is now well established, and enjoys popular support levels of around 70%.

More

Where in the world is public broadcasting?

Licence fees do not guarantee independence

Taxpayer funding for public media clearly takes varying forms around the world, but even a system that does without state subsidies and funds public service broadcasting through a direct levy does not guarantee the independence of those outlets. A lot depends on who collects the fee. If the state does it, there is a danger that the media will be manipulated for political ends. In Tunisia, for example, a fee to fund public broadcasting is collected with the consumer electricity bill, and it goes into government coffers. The rest is funded from general revenue, which makes corruption and abuses possible, as our correspondent in Tunis points out.

In India, the government has a strong voice in any corporate decisions at the public broadcaster – for example, as regards the creation of new positions.

On the European continent, stronger government control of public broadcasters is becoming a trend, notably in eastern Europe. In Poland, the conservatives in power since late 2015 have forced the public broadcaster TVP to fall in line with the policies of the ruling PiS party. The entire TVP executive body was replaced by party loyalists, and some 200 independent journalists left the station.

Poland is not the only country where free and independent reporting has come under pressure, as the 2017 press freedom ranking from the NGO “Reporters Without Borders” shows. It finds that press freedom has diminished in 61 of the 180 countries listed, including in countries like France, Spain, Portugal and Italy. Switzerland has sat in seventh place in the worldwide ranking two years in a row.

Discussions in neighbouring countries

Funding for public broadcasting is also a hot topic among Switzerland’s neighbours, too. In Italy, for example, automatically charging the fee along with people’s electricity bills was introduced in 2016. Meanwhile, Social Democrat and former Italian president Matteo Renzi has started a debate as to whether the licence fee should be abolished altogether.

In Germany, there is frequent criticism that political interests have representation on the boards of publicly-funded broadcasters. In France, the government does not control public media outlets but can put them under greater pressure to save money, which can create issues of quality.

So, public broadcasting and its funding are on the political agenda all around the world, not just in Switzerland. It is clear that there will be further upheaval in the Swiss media world, even if the voters turn down the “No Billag” initiative and leave the status of broadcasting as it is in the federal constitution.

In 2019, the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation is due to enter into negotiations regarding its continued mandate, and the federal government may call for changes. This summer, the government is starting a consultation process on new broadcasting legislation. This legislation is intended to regulate the role of online media and later replace existing legislation on public broadcasting as a whole.

The ten-language platform SWI swissinfo.ch is a business unit of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation, and half of its funding comes from licence fees.

Here is a more in-depth look at the public media situations in the countries mentioned above:

+ China: Dependent on the state

+ Brazil: The powerful media oligarchs

+ India: Direct state funding and censorship

+ Russia: State control over all media

+ Italy: Public broadcasting under pressure

+ Japan: No ads allowed

+ France: Paris dreams of a French BBC

+ Germany: Public media must do its homework

+ USA: Funding from Congress

+ Spain: Financing via private channels

+ Tunisia: Susceptible to corruption

China: dependent on the state

by Jufang Wang, London

Since Chinese media depend on the state for their journalism and content, there are no public service media per se in China. Before privately owned Chinese news portals like Sina, Sohu and Netease started up in the late 1990s providing news online, all media organisations and companies in China were either state-owned or state-controlled.

In China, media are “the eyes, ears, mouth and tongue” of the Communist Party, the government and people. At the top of the pyramid is the national state broadcaster CCTV. Its management is very interested in international collaboration with partners from other countries, including the West.

The Communist Party demands the loyalty of media, the maintaining of “correct public opinion leadership” and the promotion of the key goals of socialism.

As regards financing, news media in China since the liberalisation of the late 1970s have become more market-oriented. Earlier they were regarded as the ideological mouthpiece of the one-party state, whereas today they are media companies funded by advertising and other commercial interests. While this market-driven media reform has changed the financial model for news media, ownership and state control remain as they were before.

The complete article in Chinese can be read here.

Brazil: media muscle of the oligarchs

by Ruedi Leuthold, Rio de Janeiro

Over 70% of national TV in Brazil is produced by four big broadcasting chains, and over half of that by the major broadcaster TV Globo.

As regards print media, the four biggest media groups have a 50% share of the readership.

State TV broadcaster TV Brasil with its cultural and education programming has an audience share of just 2%.

The Globo corporation is criticised for having so much power over information. On the other hand the corporation can afford to hire the best journalists, and the same goes for writers and directors of telenovelas, which appeal to a mass audience and tend to bring the huge country together. Often enough, in their own way, the writers bring social criticism and consciousness-raising into their stories.

According to a Reporters Without Borders study, five families control the 50 broadcasters in Brazil with the most reach. It is a lucrative business. Members of the Marino family, which owns Globo, are among the ten richest Brazilians. Edir Macedo, the evangelical preacher of the competing broadcaster Record, ranks 74th on the list.

The complete article in Portuguese can be read here.

Prasar Bharati: India’s public broadcaster

With 67 television studios and 420 radio stations, Prasar Bharati, which is an autonomous body, is one of the largest public service broadcasting corporations in the world.

Prasar Bharati, India’s public service broadcaster, was set up by an Act of Parliament in 1997. It runs the national television and radio networks Doordarshan (DD) and All India Radio (AIR) respectively. It is administered by the Prasar Bharati board, which is tasked with fulfilling the broadcaster’s statutory mandate of informing, educating and entertaining the public while promoting ideas of national integration.

Content and reach

Prasar Bharati is mandated to provide content that serves the human development needs of India’s opportunity-deprived population. Therefore, a substantial part of its programming relates to education, health, agriculture, women’s issues and so on.

However, the share of commercial entertainment in DD’s content pie has been growing in recent years due to a need for advertising revenue. Most of DD’s content is outsourced while AIR generates most in-house.

Prasar Bharati’s radio and television arms have phenomenal reach and penetration. AIR has a reach of 99.2% of the country’s 1.3 billion population. DD, with its 1,416 terrestrial transmitters, has a potential reach of 90% of the population. However, both arms of the public broadcaster are plagued by lacklustre programming, which is the primary reason for its falling numbers of listeners and viewers. According to a 2014 government-sponsored report, DD’s viewership was down to just 8% of the television-viewing audience, with even poor rural households having mostly switched to satellite television.

The only times DD and AIR witness a spike in audience are when they broadcast big-ticket events such as cricket matches or the prime minister’s popular monthly radio address to the nation, Mann Ki Baat. However, AIR scores over the private radio players in the country’s remote areas where FM signals do not have sufficient penetration.

Funding and independence

Prasar Bharati is funded primarily by the state and does not earn any licence fee. It generates some revenue of its own, although this falls far short of its budgetary needs. For example, in 2016-17, the government’s grant to Prasar Bharati was INR3156 crore (CHF488.3 million). The same year, the total revenue earned by DD and AIR was only INR1282 crore (CHF198.4 million). In recent months, there has been a proposal to corporatise Prasar Bharati and this could have an impact on the broadcaster’s funding model.

While the law grants full autonomy to the public broadcaster, its board needs the approval of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting on matters such as new projects, recruitment, creation of new posts, and sale or mortgage of assets. This has sometimes led to friction between the board and the government, over alleged undue interference. Other concerns such as members of the board being political appointees and the top bosses of both DD and AIR being senior bureaucrats, have been raised.

Russia: even private media under state control

by Fjodor Krascheninnikow, Jekaterinburg

In Russia there are no public service media – electronic, online or print – remotely comparable with those in Switzerland. All media in Russia are either completely state-owned or private.

In practice, however, even “private” media are under state control, since any private ownership in Russia requires state approval or at least toleration to exist at all. Thus “Public TV”, a broadcaster set up a number of years ago by then-president Dmitry Medvedev, is a purely state-controlled TV station, which depends financially, politically and content-wise on the government.

Russians pay no licence fee. This does not mean that TV and radio are completely free, for all these media are paid for out of the national budget – which means that they are supported by the taxpayer, and taxes are deducted from earnings at source. There is no transparency as regards costs in the media sector.

The state controls all relevant media (TV, radio, online, print) in detail and prescribes what, how, when and in what form reporting is allowed or not. The people seems to accept this. Asked if they would be prepared to pay a licence fee in return for democratic control of media, almost all Russians would say “of course not”.

The complete article in Russian can be read here.

Italy: public broadcasting under pressure

by Angela Katsikantamis, Rome

In Italy, there is currently a debate about the licence fee. This unpopular tax funds 70% of radio and TV programmes of the state broadcaster RAI.

Matteo Renzi, leader of the centre-left Democratic Party, has suggested abolishing the licence fee. This has caused heated discussion. It also put paid to the illusion that the change to the billing system in July 2016 had ended controversy about the fee.

Since that time the fee has been billed to consumers as part of the electricity bill, whether they consume RAI programmes or not. In other words: if you have electricity, you pay the licence fee. The annual fee was reduced from €100 to €90 (CHF116 to CHF104). Following this change of system, revenue increased 0.8% to about €1.8 billion.

The national broadcaster is funded up to 70% from the licence fees, the rest being paid for by advertising revenue.

The basic idea of having a national public service TV broadcaster is to provide programming that is as free as possible from commercial pressures. 26.6% of broadcasting by RAI’s three main stations are intended for information and analysis, 12.4% for cultural affairs, and 10% and 16% respectively for foreign films and entertainment generally.

As regards radio, RAI only has about a quarter share of the market. The private broadcasters have most of it.

Print media in Italy are owned by large private-sector publishing companies. However, the state subsidises qualifying newspapers and online media to the tune of €10 million a year. Since the latest reforms in 2017, seven categories of publishers qualify for government support. They include non-profit organisations and consumer associations which publish magazines on their field of activity.

The complete article in Italian can be read here.

Japan: public broadcasters can’t advertise

by Fumi Kashimada, Lucerne

In Japan, NHK is the sole public service broadcaster. It runs numerous radio and TV stations around the country and a sizeable overseas broadcasting service called NHK World (Radio Japan/NHK World TV). Its broadcasts have a market share of 30%. The other 70% is accounted for by 127 commercial broadcasters, of which 118 belong to the five major Tokyo-based networks.

NHK is 95% funded by licence fees. By law, NHK may not carry advertising, for advertising revenue is specifically forbidden. The ban on advertising is very strict and even extends to the lyrics of songs. For example, a singer had to change the wording of her song from “red Porsche” to “red car”.

All households and companies with receiving devices are legally obliged to pay the fee. The monthly fee for households with terrestrial devices is ¥1,260 (CHF11), with satellite ¥2,230. Companies also pay these fees.

Only around three-quarters of those supposed to pay the fee actually do so, as there are hardly any consequences for failing to pay. That might change in future, following a recent supreme court decision.

The five main commercial networks fund their operations through advertising.

France: Paris dreams of a French BBC

by Mathieu van Berchem, Paris

In France public broadcasters are having a tough time. The threat comes not, as in Switzerland, from a popular initiative, but from the president himself: Emmanuel Macron has described the state of public broadcasting in the country, according the magazine L’Express, as a “disgrace to the Republic”.

A government plan now intends to merge France Télévisions and Radio France, which would result in a company with 17,000 employees and a budget of €3.8 billion (CHF4.4 billion). The model being touted is Britain’s BBC. The aim of this reform would be to create synergies, especially in news programming.

Another Macron project involves the licence fee. Currently TV owners are charged €138 a year. This brings the state coffers some €4 billion, of which 66% goes to France Télévisions, 7% to Arte and 16% to Radio France. What is planned is an extension of the fee to people with internet access. Currently the fee is linked to the residence tax. This is what Macron wants to change, so it remains to be seen how the fee would be collected.

The main national TV broadcaster France 2 has for a long time been torn between two aims. On the one hand it has to compete with the main commercial broadcaster TF1 – both stations have lost market share in the past year (20% for TF1 and 13% for France 2) to news channels. On the other hand, quality is at risk, particularly since the station has been banned from carrying advertising after 8pm. That meant a loss of €500 million to its budget.

The complete article in French can be read here.

Germany: per-household fee for public broadcasting

by Petra Krimphove, Berlin

It was a milestone when Sat.1 went on the air as the first private broadcaster in Germany in 1984. Almost at the same time, RTLplus started. Since then, there has been competition in Germany’s dual broadcasting system between the public broadcasters like ARD and ZDF and the commercial stations.

As private-sector companies, the commercial broadcasters have to support themselves with advertising revenue or, in the case of Pay TV, subscriptions. That increases pressure on the ratings: the more people watch, the more money there is in the pot. So the stations run what audiences want.

Public service broadcasters have a cultural and news responsibility to fulfil. Their news and talk shows are still highly regarded by Germans as the most reliable source of information in the media jungle.

As public-sector organisations, ARD and ZDF are mainly funded by the licence fee. No less than €8 billion (CHF9.3 billion) a year is made available to the public broadcasters to make programmes. Every household in Germany has to pay €17.50 a month, whether the people concerned watch channels like ARD and ZDF or not.

The complete article in German can be read here.

US public media: a funding mix

By Lee Banville, Montana

Public media in the United States is a decentralized service that provides content across broadcast and digital platforms. The organizations are not governmental agencies, but rather local public institutions funded by a mix of federal funds, individual supporters and corporate and foundation sponsors.

The two primary national networks, Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) on the television side and National Public Radio (NPR) on the radio side, are separate entities that are membership organizations and provide content to their local owners – actual terrestrial broadcast stations.

These services cover a variety of areas, including news and current affairs, children’s programming, historical and current documentaries, dramas and comedy programs. The national systems are augmented by hundreds of local member stations that often produce their own programming that can be distributed locally or by other local stations. Some critics have questioned the need for public broadcasting as cable outlets increased in number, but public opinion surveys have found that 70% of the public approves of government support for PBS and NPR.

Read the full story on US public media here.

Spain: funding by private-sector broadcasters

by José Wolff, Madrid

In Spain the idea of public broadcasting goes back to the founding of Radio Nacional de España in 1937 and later Televisión Española in 1956. Since 1978 access to information has been enshrined as a basic right in the constitution: the government must provide a national radio and TV service.

Both stations are currently part of the Corporación Radiotelevisión Española (RTVE), a company that is 100% owned by the state. The law guarantees its independence from the government of the day, political parties and private-sector interests. The RTVE is accountable only to parliament. The nine-member board is elected jointly by both houses of Parliament.

The state provides half the funding of RTVE out of general revenue, the other half being derived from taxation of telephone companies (0.9% of revenue), private TV broadcasters (3% of revenue) and Pay-TV stations (1.5% of revenue).

The private radio and TV broadcasters at national level are large groups of companies, some of them international (like Mediaset, Prisa and El Mundo), Spanish publishing companies (like Vocento and Godó), and the Catholic Church. They are mainly financed by advertising revenue.

The complete article in Spanish can be read here.

Tunisia: risks of corruption and abuse

by Rachid Khechana, Tunis

One of the oldest public media in Tunisia is the daily newspaper “La Presse de Tunisie” and its Arabic equivalent “Assahafa”. In recent years circulation of both has declined. They are not independent, and critics thinking of the censorship of ideas in the former Soviet Union have dubbed them “Tunisia’s Pravda”.

As well as these newspapers, the state owns more than 98% of the official press agency Tunis Afrique Presse. This agency employes a staff of 304, of whom 168 are journalists.

Maintaining a public radio broadcasting service requires a considerable investment by the state. It has to provide 14 million dinar (CHF5.6 million) to pay salaries, which amount to 76% of total costs. Radio-TV licence fees collected via the electricity bills bring in 13 million dinar, and advertising is estimated to bring in a further two million dinar.

As regards public TV, the situation is even worse, for the broadcasters’ budget amounts to 56 million dinar, of which 14 million dinar is covered by advertising revenue and five million dinar come from programme sales. The rest has to come from the state.

For the purpose of refinancing, fees are being charged through the electricity bill. But that is not enough. The fees collected do not go directly to radio and TV but into general revenue, which opens the door to corruption and abuse. Transparency is lacking, since the amount the consumer actually provides to the radio and TV stations is not made public. That was the case before the Tunisian revolution of 2010-2011 and it is still the case.

The complete article in Arabic can be read here.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.