Gender bells, gender bells, ringing in the Alps

The Swiss children’s book Schellen-Ursli (A Bell for Ursli) made the traditional spring festival of “Chalandamarz” world-famous. Now, controversy is simmering in the Swiss Alps, as even the custom’s last strongholds have allowed girls to join in. SWI swissinfo.ch visited Zuoz, a village torn between tradition and gender issues.

It’s the typical Swiss mountain village as pictured by foreigners. Massive stone houses with elaborately painted walls line the streets of Zuoz, a village in the high valley region of Engadine in the eastern Swiss Alps. A fountain decorated with flowers stands in the main square, with its schoolhouse and town hall. And overlooking the village is the internationally renowned boarding school, the Lyceum Alpinum.

But the idyll is deceptive. For nearly a year, the Alpine village has been riven with strife. The cause is a culture war between tradition and gender politics – a conflict that is taking place around the globe. In Zuoz, it’s about nothing less than the Engadine region’s best-known custom, Chalandamarz, a procession held each year on March 1 in which the local boys go around the village, ringing bells and singing, in order to drive out the winter.

Just the boys – until today, that is. And therein lay the problem.

Story of emancipation

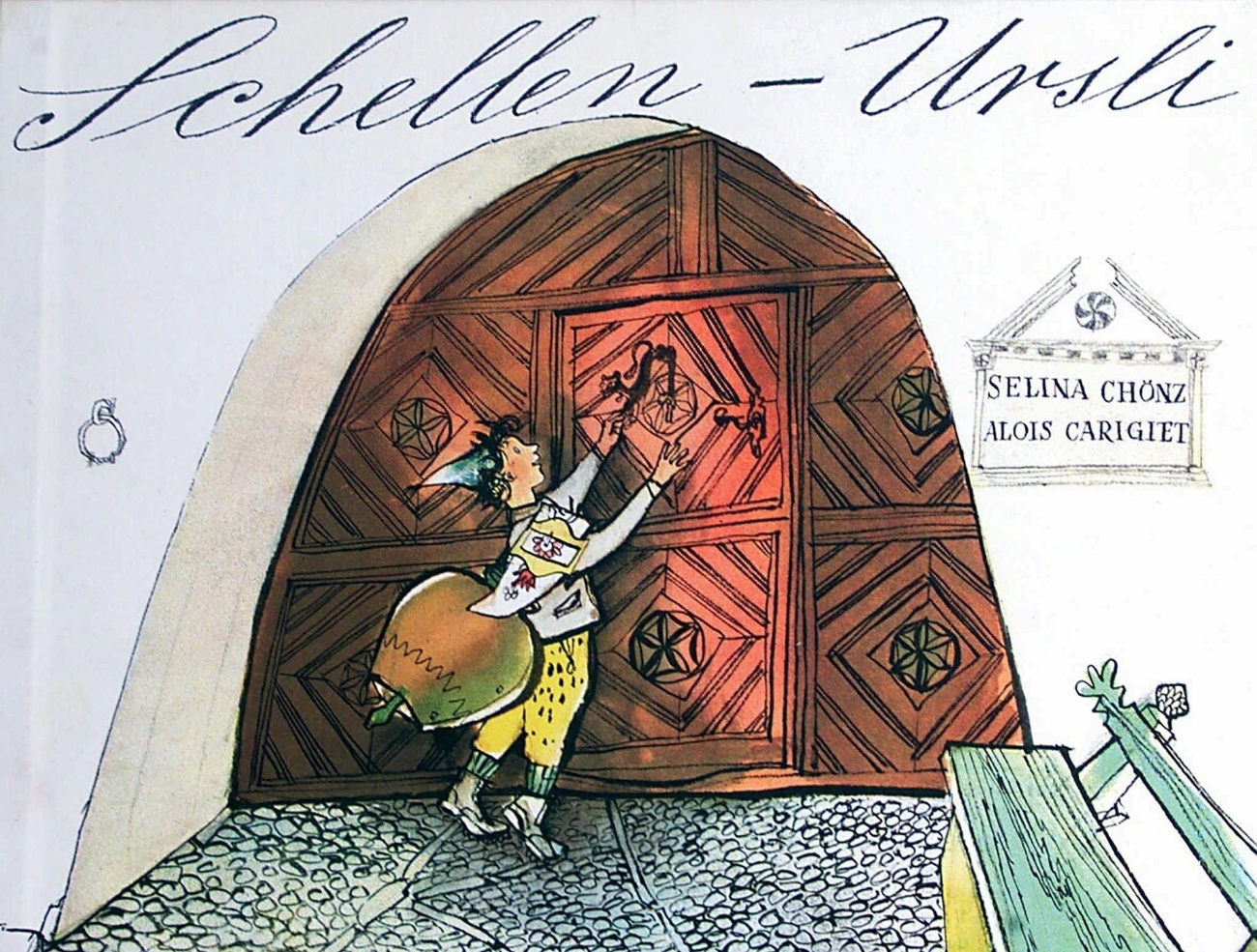

Chalandamarz became known to a global audience thanks to the illustrated children’s book A Bell for Ursli. Published immediately after the Second World War, in 1945, the story with its iconic imagery has, over the decades, become Switzerland’s second-most successful children’s book – eclipsed only by Heidi. It has been translated into eight languages, including English, Japanese and Chinese.

The story is about little Ursli, who has been given only a tiny goat’s bell for Chalandamarz. The other boys in the village make fun of him because of this. As a result, Ursli will have to walk at the back of the cowbell procession – an ignominy he cannot accept. So he fights his way through the deep snow to the family’s Alpine hut, where a huge cowbell hangs. He returns to the village with it the next day, and is now allowed to lead the procession because he has the biggest bell.

It’s an emancipation story with a male cast. Ursli also has a sister, Flurina, but, like all the other girls in the village, she is not allowed to join in the procession. This gender division probably didn’t bother anyone in the 1940s. In Zuoz, which for years left the tradition untouched, the issue has now sparked controversy.

What set it all off was an initiative by the municipal council to open up the custom. The idea was that the girls should be treated completely equally – that is, also take part in the procession, sing along and wear blue peasant smocks and red tassel hats, just like the boys.

More

Sweeping stereotypes out of school books

This is required not least by the principle of equality enshrined in the Federal Constitution, which is binding on all schools in Switzerland. In Zuoz, which takes the tradition more seriously than almost any other village in the Engadine, Chalandamarz is a compulsory part of the school year.

But the revolution met with resistance. The voting at the municipal assembly last June revealed the deep rift running through the village. While many women, in particular, spoke out in favour of girls’ participation, one voter declared that for him Chalandamarz would no longer be the same. Someone else suggested involving the girls in a different way: “They could decorate the festival hall, for instance.”

The mayor felt compelled to make a spontaneous move and withdrew the proposal for reconsideration. However, the controversy remained. It was a topic best avoided at family mealtimes, one resident confided during a visit by SWI swissinfo.ch late last summer. She herself was in favour of the revision, she said. Others meanwhile, including some women, just shook their heads. It was unthinkable that Engadine customs should be overturned by gender activists from the lowlands, they said.

Dark side of age-old customs

Mischa Gallati, cultural scientist and lecturer at the University of Zurich, is not surprised by the scepticism reigning in Zuoz. The tradition originated at a time when society was clearly organised along gender lines. If the ritual were changed, then this duality would also be called into question. “It’s linked to fears. There’s a defensiveness, a falling back on traditional patterns,” he says.

But this is only one aspect of the dispute, according to Gallati. The discord within the municipal assembly showed that the whole issue was also a proxy debate. “Customs have their dark side. They are always also about exclusion, about who has power, and who belongs.”

As in many Swiss mountain villages, locals and newcomers stand opposed in Zuoz. This confrontation is exacerbated because the language spoken here is Romansh, a Swiss national language spoken by about 50,000 people. Many of the newcomers make no attempt to learn it.

Despite the resistance, however, Gallati takes it for granted that the custom will change, as has already happened in other nearby villages. Customs are an instrument of self-affirmation, he explains. Chalandamarz dates back to an agrarian society, where the passing of the seasons was central. “These rituals were built around this, and now they are being charged with new content,” he says.

More

They do what? Five frankly bizarre Swiss traditions

Phallic connotations

Andrea Könz takes a more critical view of the change. She is the widow of Steivan Liun Könz, son of the author of A Bell for Ursli. Of course, traditions have to evolve, she agrees, “but my main criticism of the modernisation is that the symbolism behind the custom is no longer understood”. Chalandamarz is a fertility cycle, she explains, and the big bells have phallic connotations. “So does it make sense to put them on the girls?”

Könz also sees a culture clash in the Zuoz debate. It was mothers from the lowlands who pressured for equal rights in the mountain villages, she says. “They didn’t see why their daughters should be left out.” It is all their demands as a whole that bother Könz. Her daughter also wanted to take part in Chalandamarz in the village of Guarda, where they lived for a long time and where A Bell for Ursli is also set.

That was back in the 1990s. Like other Engadine communities, Guarda discussed whether to include girls several years ago. “But the gender debate wasn’t as crazy back then as it is today,” Könz says.

Diversity, she believes, is too often linked to outward appearance, and equality is confused with uniformity. In many villages, girls had their own role in the ritual. This is where she sees a potential for renewing the custom without betraying it. “It’s then a matter of not simply devaluing the role of girls as insignificant, but of giving it equal attention,” she says.

New beginning

Zuoz chose a way out of the dilemma that is both Swiss and un-Swiss. This year, girls took part in the procession for the first time, dressed in the same way as the boys, but without carrying bells.

A committee, tasked by the municipal council with resolving the issue, reached this compromise on its own. The decision was not brought before the community, which was instead presented with facts on the ground – uncharacteristically for Switzerland, which functions as a direct democracy.

According to Ramun Ratti, vice-president and interim mayor of Zuoz, the “vast majority of community members” were in agreement that girls should also participate. So now, with the custom’s new look, peace should return to the village.

Chalandamarz is important for cohesion and identification, Ratti stresses. He also feels pressure from the lowlands. “If you look at the big picture, we’re in the minority.”

Ratti strongly believes that the gender debate must be addressed. “But it’s important to develop the tradition carefully.” This has always been the case, he explains. “The blue smocks and red hats were only added on in Zuoz after the war.”

Moreover, the whole purpose of the tradition has changed, he says. “In the past, there was a link with mercenaries: as well as driving away the winter, it was an occasion for the boys to present themselves in the village.”

Today, he says, the event is mainly for children. This is perhaps what influenced his thinking most. “My daughter was really looking forward to taking part,” he says.

Edited by Balz Rigendinger. Translated from German by Julia Bassam

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.