How a Polish envoy to Bern saved hundreds of Jews

Aleksander Ładoś, a Polish envoy to Bern during the Second World War, saved hundreds of Jews from the Holocaust with help from Jewish associations active in Switzerland and the United States.

It’s 1942. Some 340,000 Jews live in the Warsaw Ghetto. After the Wannsee ConferenceExternal link in January, the machinery of the Holocaust is set in motion. By July, Germans will begin clearing the Ghetto. Only Jews with foreign passports issued by a neutral country or the United States can enjoy a fragile calm. Germans leave them alone since they may still prove useful should there ever be a need to trade them for German citizens held captive abroad.

In the Swiss capital of Bern, which knows of the war mainly from newspaper reports, a network emerged of Polish embassy staff and leaders of orthodox Jewish associations.

This article is based on an original investigationExternal link by journalists from the Polish newspaper Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. swissinfo.ch has not verified the contents.

Members included chargé d’affaires Aleksander Ładoś, his right hand Juliusz Kühl, consul Konstanty Rokicki and adviser Stefan Ryniewicz. But also Jewish activists, among them former member of the Polish parliament Abraham Silberschein, founder of the Relief Committee for the War-stricken Jewish Population, and rabbi Israel Chaim Eiss, head of the Swiss branch of Agudath Israel, an orthodox movement. Finally, the Sternbuch family from Montreux who had links to orthodox associations. Together they formed a base for an unprecedented operation, codenamed “Passport Services”.

Hundreds of previously unpublished documents from the Federal Archive in Bern, reviewed by Dziennik Gazeta Prawna (DGP) correspondents, prove that it was in fact Ładoś and his subordinates who masterminded the evacuation of Polish Jews by providing them with South American passports. They also reveal that Ładoś was one of the first people in the world to anticipate the full extent of German plans towards the Jews. He was therefore able to offer the Polish government-in-exile’s help escaping the Holocaust in it’s very early stages.

Diplomatic ciphers

“The question ‘How can we equip Polish citizens with foreign passports?’ first appeared at the turn of 1939 and 1940, after Poland was invaded by Germany and Russia. We were concerned about certain individuals living under Russian occupation and wanted to devise a way to get them to safety,” Juliusz Kühl testified to a Swiss policeman in 1943.

Polish diplomats soon found a solution. It led through Swiss notary Rudolf Hügli, the honorary consul of Paraguay, who wanted to make some extra money by issuing false passports. At first he was paid by the Polish embassy.

The scheme really took off in 1942. The list of people qualified for rescue was compiled by the Jewish members of the network. It included rabbis, students, wealthy merchants: people capable of restoring orthodox elites after the war.

Money for Hügli started flowing through Polish diplomatic mail from the Jewish community in the United States. After the US entered the Second World War and all communications across the Atlantic were subjected to censorship, Ładoś offered diplomatic ciphers enabling conspirators to send messages and money across the ocean. This channel later became the conduit for first revelations about the Shoah [Holocaust] to reach American shores.

Out of hundreds of documents inspected by the DGP, not one implied Polish diplomats were profiting from the scheme. Motives for the undertaking can be found in a diplomatic cable from the Polish foreign ministry to the embassy in Bern sent on May 19, 1943: “The Ministry has been informed lately by Jewish organisations of the possibility of using South American passports to rescue Jewish individuals from death by German hands. Arguments of purely humanitarian nature dictate going the extra mile in that matter.”

More

Ensuring the Holocaust ‘never happens again’

When the instruction from London arrived in Bern, the life-saving scheme was already under way.

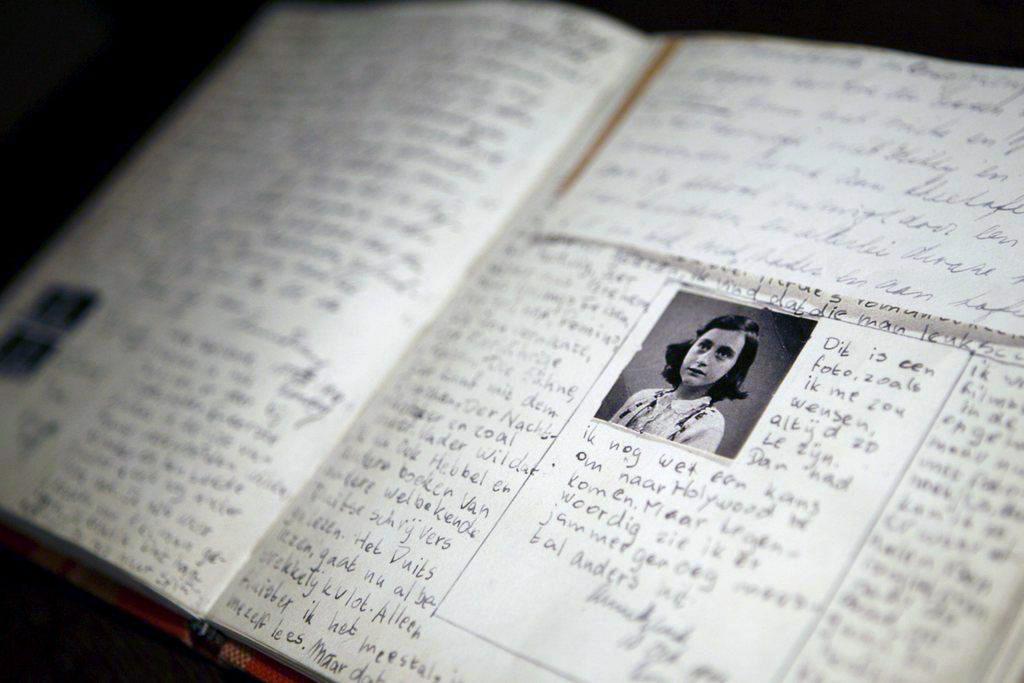

Passport photos

Rumours about it spread quickly. Letters soon started arriving from the Ghetto, partly thanks to bribed Germans. The correspondence included personal data and photos attached with thin threads.

This was the basis for the envoy’s men to forge documents. The DGP has seen them in the Federal Archive in Bern, Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem and a personal collection of one of the survivors’ descendants.

Many of those passport photos had been cut from family pictures: a man smoking a cigarette; a couple holding a baby in a sleeping bag. The letters with Adolf Hitler stamps and swastikas were sent from the General Government to Switzerland. The photos had to be glued into passports and then sent back to the Ghetto with photocopies authenticated by a notary. Some were authenticated by Hügli himself.

“Generally, passport services were run by the Polish diplomatic mission,” wrote the Swiss police, who kept the scheme under surveillance.

“Once a passport has been issued, it remained in the consulate. Then members of the staff mailed a photocopy to the German authorities in General Government, in either Warsaw or Kraków. Based on those documents, people were sent to internment camps rather than extermination camps. The Polish diplomatic mission was familiar with this method of saving Polish Jews from death,” wrote Swiss federal police chief Heinrich Rothmund after a talk with Stefan Ryniewicz in October 1943, five months after the fall of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising and the final liquidation of the Ghetto itself.

The photocopies made “Paraguayans” eligible for transfer from the Ghetto to Pawiak prison in Warsaw, run by the Gestapo, the German secret police, and then on to a transition camp in the French town of Vittel, where they waited to be exchanged for German citizens interned abroad.

What’s more, this scheme allowed for the safe evacuation not only of “Paraguayans”, but also freshly “naturalised” citizens of Honduras, Bolivia and El Salvador. The forged documents differ in details. For example, Paraguayan passports omit the bearer’s place of birth, which was included in the Honduran document. Therefore “citizens” of this small Central American country ended up coming from such exotic places as Przysucha or Sosnowiec.

Hundreds saved

“My father used to tell me that people in the Ghetto tried to learn about the countries for which they had passports – in case they were asked. One person wanted to know what language they speak in Paraguay, and another answered ‘Paraguayish?’ My father liked that one, and we’d laugh,” recalls Naomi Seidman, daughter of Hillel Seidman, one of the survivors who was sent to Vittel thanks to the forged documents.

Aside from coordinating, Ładoś also provided diplomatic cover. This proved crucial when South American governments found out about illegal issuance of passports by consuls and refused to acknowledge the documents.

In September 1943, the government in Bern stripped Hügli of his status as honorary consul and Germans delegated their own special committee to Vittel for passport verification. Soon, the majority of Jews transferred to France were sent back to General Government. Unfortunately, this meant one place only: Auschwitz extermination camp.

The Polish envoy tried every possible channel to prevent this from happening. He intervened in the Swiss foreign ministry, lobbied Americans and got in touch with the papal nuncio in Bern, archbishop Filippo Bernardetti, a friend of Kühl’s and supporter of the life-saving scheme.

Polish diplomacy used both formal and informal channels to pressure South American governments into recognising the forged documents. Unfortunately, the success came too late for many “South Americans”. According to the Polish foreign ministry’s estimates from 1944, out of 4,000 issued passports, 400 saved their bearer’s lives.

“When Kühl was talking about the Polish envoy, he described him as a real saviour,” said Israel Singer, former secretary general of the World Jewish Congress in an interview with the Globe and Mail’s Mark MacKinnon, who also worked on a piece about Ładoś. His findingsExternal link were published in the Canadian newspaper on August 8.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.