How to counter lies and propaganda in war zones

Information is a powerful weapon. In the Russia-Ukraine war, as in many conflicts today, truth has become an easier target than ever thanks to digital technologies. Peacebuilding experts explain to SWI swissinfo.ch what lies behind the information chaos and how to reclaim the facts.

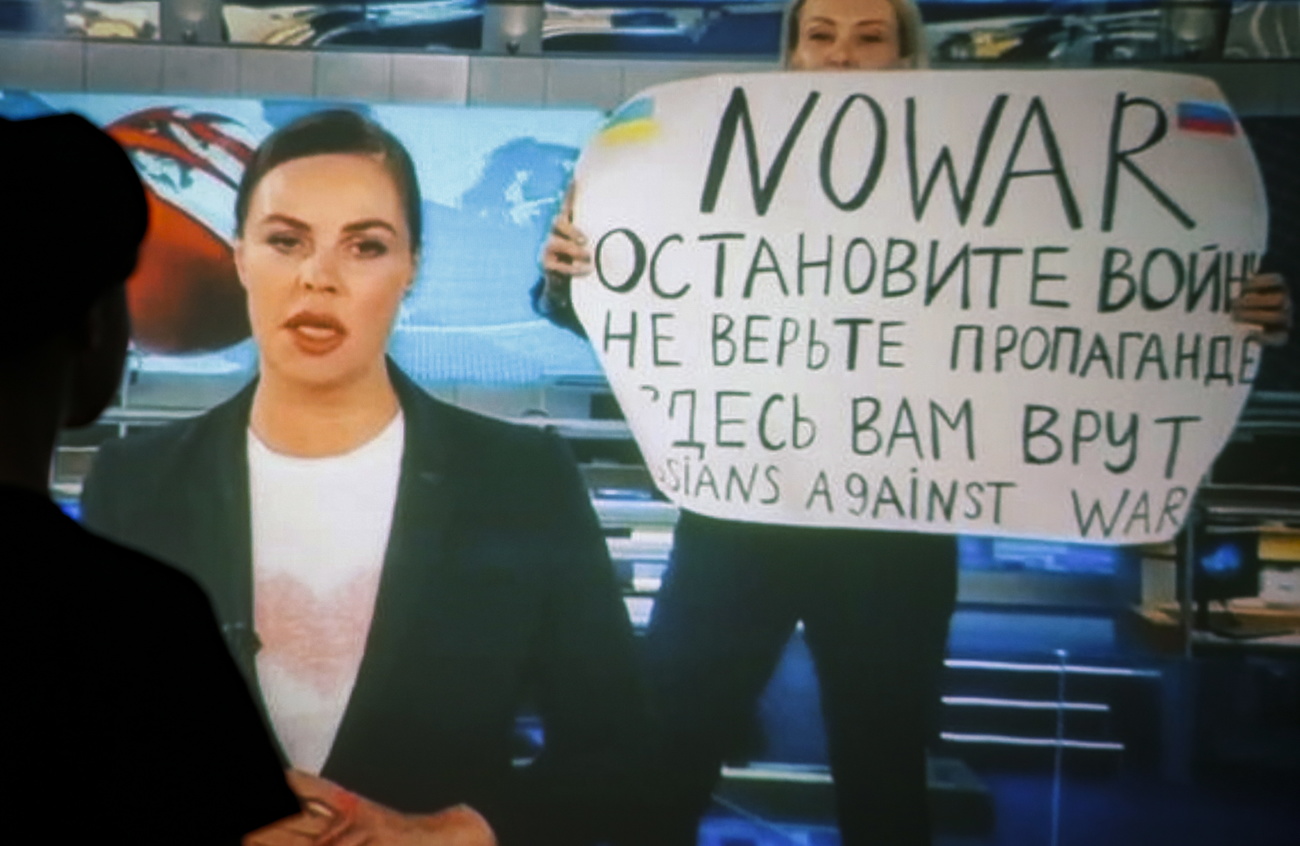

Weeks before the first Russian missiles hit Ukrainian cities, the Kremlin made a series of claims about the government in Kyiv. Ukrainian forces, Russian state-sponsored television said, were committing genocide in the breakaway regions of Donetsk and Luhansk along the Russian border. To help paint Ukraine as the aggressor, doctored videos of alleged victims landed on social media.

Once the invasion began, the disinformation offensive kicked into high gear. Pro-Russian accounts on closed messaging app Telegram spread false reportsExternal link that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky had fled the country. Then, ten days into the war, Russian legislators approved a “fake news” law that compelled independent media and foreign journalists in Russia not following the Kremlin’s narratives to suspend their work.

“This is the playbook – to come at it from different angles [and] create an atmosphere of chaos and confusion,” said Emma Baumhofer, digital expert at the peacebuilding institute swisspeaceExternal link.

Propaganda has long been a feature of warfare, as adversaries try to win hearts and minds as well as battles. But with social media, the internet and smartphones, warring sides can now weaponise information with relative ease, speed and reach. As misinformation spreads online and then makes its way offline, a “complex information environment”, as Baumhofer calls it, takes hold, making it difficult to tell fact from fiction.

Accentuating crisis from Ukraine to Africa

Like the Russians, the Ukrainian side has contributed to the information war with its own propaganda campaign. Officials have claimed, for instance, that the number of fatalities among Russian soldiers is much higher than United States intelligence estimates or figures released by the Kremlin. They’ve even paraded alleged prisoners of war before the pressExternal link.

An actor in any war would want to emphasise its successes to motivate troops, as Julia Hofstetter of Swiss think tank forausExternal link points out.

“In many conflicts, digital disinformation is used to mobilise support within your own population, destabilise the enemy or spoil a peace process,” said Hofstetter, who specialises in the cyber dimension of conflict and digital peacebuilding.

In some cases, civilians, non-state actors and even other governments join the information war. In Ukraine, ordinary citizens have posted videos on social media that are difficult to verify and purport to show captured Russian soldiers. Volunteer hackers have attacked Russian government websites and state media in an effort to hurt the country’s propaganda machine. Strikingly, said Baumhofer, the US published some of its own intelligence to undermine Russia’s pre-invasion narratives.

More

Swiss businessman helps Ukrainian refugees

But interfering in conflicts abroad is nothing new, not least for Russia. For years the country has used many of the same disinformation strategies seen in the current war, said Baumhofer. One example is in the Central African Republic (CAR). Researchers at the United States Institute of Peace foundExternal link that an increase in violence following contested elections in the CAR in late 2020 “coincided with fake news and propaganda thought to originate from Russia and France”.

According to Nicolas Boissez, head of communications at Swiss NGO Fondation Hirondelle, Russia wants to broaden its influence in the African country, where fighting between government forces and non-state armed groups has escalated in the past year. Disinformation has become an important feature in a tense political and security situation, Boissez added.

Fighting back with facts

The impact of disinformation on people in the country is “significant [and] accentuates the security crisis and further weakens the work of actors involved in building peace”, writesExternal link Fondation Hirondelle.

The Lausanne-based NGO has spent more than 25 years supporting independent media and training journalists in countries caught up in crises, with the idea that fact-based journalism can contribute to peace. Its work in the CAR shows some of what can be done to tackle disinformation.

“The core of our response is to provide people with the facts and explain those facts in the simplest way possible [and] in a language they understand,” said Boissez. “We focus on information that’s close to their daily preoccupations and create a bond of trust in that way.”

Two years ago the NGO launched a campaign to fight disinformation together with Radio Ndeke LukaExternal link (RNL), which it founded in 2000. This included creating a fact-checking unit at the station, now the most popular media outlet in the country. The fact-checkers’ work is broadcast on RNL as well as on partner stations, the web and social media, to reach as many people as possible.

Verification has featured prominently in the Ukraine war as well. Before the invasion even began, journalists and civil society organisations like Bellingcat used open-source online intelligence tools (OSINT) to debunk images and videos claiming to show Ukrainian aggression, revealing gaping holes in Russia’s pretext for invasion. Zelensky himself has shared videos filmed on a smartphone in which he refutes Russian claims.

But fact-checking and supporting independent media are not the only ways to fight disinformation.

“Being presented with the facts is not enough to change people’s minds,” said Baumhofer. “We have to address the root causes [that] are fuelling vulnerability to disinformation.”

In the CAR, Fondation Hirondelle has enlisted opinion leaders like artists and musicians to appear at public events designed to raise awareness about “fake news” and how to avoid becoming agents of misinformation.

According to a glossaryExternal link established by the non-profit network First Draft, disinformation is false information deliberately created or shared to cause harm. Misinformation is false information that is not intended to cause harm, such as information inadvertently shared by people who don’t know the information is false.

But both Hofstetter and Baumhofer also see the need for digital literacy, especially to help people stuck in a news blackout. In Russia, where the government has restricted access to Twitter and Facebook, hundreds of thousands of peopleExternal link have reportedly used a VPN (virtual private network) to seek out other news sources. Yet most people are not aware of this option or how it works, said Baumhofer.

Pressure for tech firms to do better

The most critical area for change, however, is social media because of the outsized role it plays in disseminating both “fake news” and verified information.

Platform moderators have been on particularly high alert in this war – the international media attention could be a factor, Hofstetter at foraus speculates. Google, Twitter and Meta, Facebook’s parent company, were quick to block Russia Today and Sputnik, two state-sponsored outlets that were barred from broadcasting in the European Union soon after the invasion began. Twitter and Facebook have also suspended or removed accountsExternal link for violating the terms of use.

But it’s a departure from tech companies’ track record. In most conflicts they have not done enough to stop hate speech and disinformation, Hofstetter said, partly because the firms are reluctant to invest resources in monitoring content in local languages in countries that are not considered large target markets.

In the worst cases, the lack of response from big tech has led to deadly violence. An independent reportExternal link found Facebook had created an “enabling environment” for violence against the Rohingya population in Myanmar in 2017, as hate speech against the community proliferated unchecked on the site.

“Platforms are really contributing to conflict because of the way they’re built,” Baumhofer said. “They tend to reward outrageous behaviour and anger because that’s what gets the most traction.”

Harnessing digital technology to promote peace is a burgeoning field, according to Julia Hofstetter of Swiss think tank foraus: civil society groups are using open-source intelligence (OSINT) to debunk disinformation while mediators are relying on crowdsourcing platforms to make peacebuilding more inclusive.

But the biggest potential, she said, lies in empowering communities, by giving people the possibility to organise at grassroots level, document war crimes and share their stories with the international community simply by using their smartphones.

As researchers working on footage from the Syrian warExternal link are showing, the technology now exists to verify user-generated material and archive it for the future prosecution of war crimes – potentially giving victims a shot at justice.

Baumhofer suggests peacebuilders could work with platforms “to make them more peaceful places for discussion”. Their experience with mediation and finding common ground between divided communities, for example, could be harnessed to help these sites make fundamental changes so they highlight commonalities between users rather than polarise them.

The bottom line is to keep pressure on tech firms to do more in all conflict situations. After all, the war in Ukraine is not their first brush with disinformation in wartime.

“Every conflict presents a new scenario,” said Baumhofer, “but we could have prepared for it better.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.