In the footsteps of Swiss settlers in Brazil and their slaves

In the 19th century, Swiss settlers owned slaves in Bahia, Brazil, a dark chapter which still remains taboo today.

In the forests of Bahia, Brazil, relics dating back 150 years bear witness to a dark history. “Over there, there was the farm,” says Obeny dos Santos on Swiss public radio, RTSExternal link. “And down here, the slaves were imprisoned and tortured”. The farm belonged to Swiss settlers who owned the slaves that worked these lands.

“Look how well-built the structure was,” says Obeny dos Santos, pointing to the remains of walls eaten away by vegetation. “This is where the slaves were kept. They worked during the day and at night they were locked in there.” Chained to a metal post, they had no chance of escape.

Swiss authorities deny these accounts

The Swiss authorities have always denied any involvement in the horrors of slavery. A few financiers and merchants did take part in this forced exploitation, but behind the Swiss Confederation’s back.

Hans Faessler, a committed historian, is challenging the Confederations view, using documented evidence. At the Federal Archives in Bern, he presents special documentation: a report that the Federal Council drew up in 1864 for Parliament, concerning Swiss nationals living in Brazil who owned slaves.

This is the first observation that the Federal Council was well informed about the situation. It even knew the price of a slave, between CHF4,000 and CHF6,000 ($4,634 to 6,951).

“This report is truly a document of great importance for Switzerland’s colonial history,” emphasises Hans Faessler. “For the first time, the issue of slavery appears in the Swiss Parliament. In the report, the Federal Council admits (…) that there were Swiss, plantation owners, traders and also (…) craftsmen who owned slaves.”

This report by the Federal Council was in response to a motion by Wilhelm Joos, a doctor and parliamentarian from canton Schaffhausen, who visited the Swiss colonies in Bahia. “Apparently, Wilhelm Joos was shocked by the reality of slavery in Latin America, in Brazil, and the first motion he tabled in the National Council called for criminal measures against Swiss nationals who owned slaves in Brazil,” explains the historian.

Traces still alive in Brazil

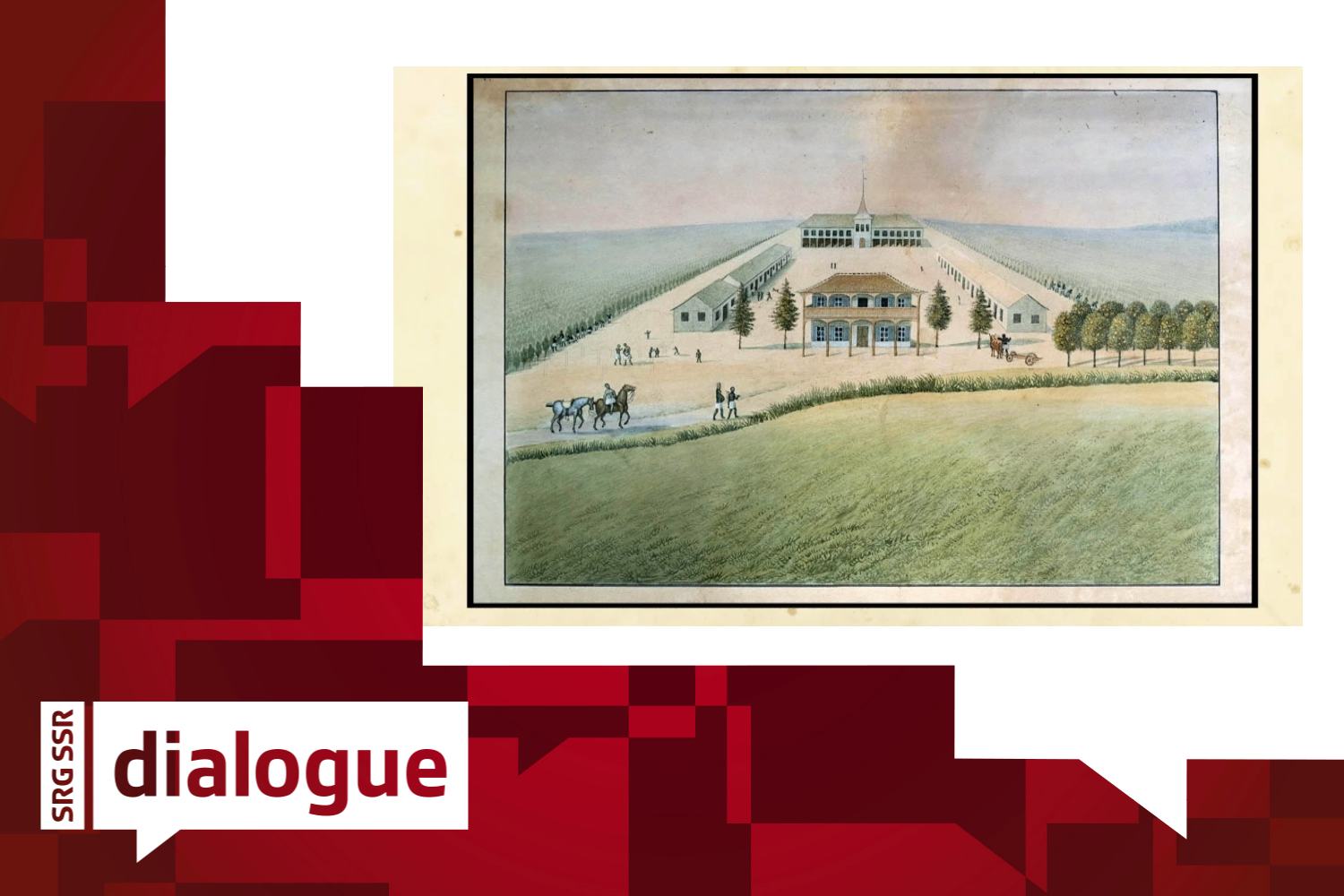

Traces of this period remain in the small village of Helvetia, located south of Bahia. Its name recalls the presence of settlers from cantons Vaud, Neuchâtel and Bern throughout the 19th century. Here, coffee and cocoa were produced. This intensive cultivation was impossible without slaves – lots of slaves.

“There were around 2,000 of them, and they were by far the majority. That’s why today 95% of the population of the village of Helvetia is black”, says Maria Aparecida Dos Santos, a resident of Helvetia. Her great-great-grandparents were deported from Angola, before being sold to Swiss settlers, sent to plantations and treated like cattle.

“The slaves all lived together, crammed into a large communal stable,” she says. “They had no privacy, no freedom, no dignity. The settlers raped the black women.”

She goes on to point out another practice of the colonists: “These black women were also considered to be breeders, so the colonists brought together strong men and strong women to produce strong children specifically to work on the plantations”.

For her, this story is “so sad that people try to forget it”. Even though history books have been telling these stories for years, “for people, these stories represented so much suffering that they tried to erase them from their memory, and therefore erase them from history”.

According to the Swiss authorities at the time, there was ‘no crime’ to report

The Swiss slave owners were never questioned by the Swiss authorities. Worse still, at the time, the Federal Council defended the colonists.

“The Federal Council said that slavery for these Swiss was advantageous, and that it was normal,” historian Hans Faessler points out in the report. “And it is impossible to deprive these ‘poor’ Swiss of their legally acquired property.”

According to the Federal Council in 1864, slavery was not unjust and against morality, since it did not involve any crime. On the contrary, in the eyes of the government of the time, “penalising the Swiss who own slaves that would be unjust, against morality and an act of violence”.

“The Federal Council became the last government in the West to trivialise, justify and excuse the crime of slavery”, says Hans Faessler. By then, France, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands had already abolished slavery. The United States put an end to the practice in December 1865.

‘Slaves worked from sunrise to sunset’

A few kilometres from Ilheus, Brazil, is the Fazenda Vitoria, or “Victory Farm”, one of the largest farms in the region. Here, nearly 200 slaves used to grow sugar cane. Today the farm is abandoned and access to it is forbidden.

For over 40 years, Roberto Carlos Rodriguez has been documenting the history of this farm, where his ancestors worked as slaves. The owners of the farm were Swiss.

“Fernando von Steiger was the second largest owner of enslaved Africans in southern Bahia,” says Roberto Carlos Rodriguez. “Here, the slaves worked from sunrise to sunset. They woke up at five in the morning and had to greet the boss. Then they’d start work. It was hard work and, as on other farms, the slaves didn’t live very long. In Brazil, the life expectancy of a slave was seven years”.

When Rodriguez talks about the involvement of the Swiss authorities in slavery, his anger turns cold.

“This farm was run at the height of slavery by two Swiss. Gabriel Mai and Fernando von Steiger were financed by Swiss trading houses,” he says. “From this point of view, it is common knowledge that the Swiss government invested in slavery through these trading houses. To say that Switzerland did not contribute to slavery is like saying that the sun did not rise this morning.”

What is the reaction today?

In 2022, Socialist parliamentarian Samira Marti from canton Basel tabled an interpellation asking the Federal Council to take a position on the 1864 report. This is the 8th interpellation in twenty years. Each time, the Federal Council’s response is the same: “The federal authorities of the time acted in accordance with the standards of the 1860s”.

“It’s a bit scandalous that the Federal Council always says that it was just the spirit of the times. And that it wasn’t the state that was involved in slavery”, says Marti. “(…) And yet Switzerland continued to accept slavery”.

Marti is calling for clarity from the government on this view of history. “It is important for the Federal Council to be quite clear today (…). For today and also for the future, in discussions on racism and inequality in general”. He even called on the government to correct the Federal Councils view representation of this history.

Fearful of possible demands for reparation, embarrassed by past compromises, the federal authorities are clinging to their version of the past for now. They have refused all requests from Swiss public radio, RTS. for an interview.

In Brazil, even if the exercise of remembering is just as painful, Maria Aparecida Dos Santos hopes to find answers in the past for her present and that of her community. “I want to do some research today because I know that there are historians in Salvador de Bahia working on the subject. There are books about what happened at that time. I realised that I didn’t know my own history, and that leaves me with a void, a strong inner feeling… very strong.”

This topic for RTS is part of over two years’ research into Switzerland’s involvement in slavery, which will culminate in an original RTS podcast (in French), the third season of the “Face cachée”External link (only available in French) collection, to be released in June.

Many other Swiss have made their fortune in Bahia. For example, Auguste de Meuron from canton Neuchâtel set up a snuff factory in Salvador de Bahia, which exported throughout Europe. It also employed slaves.

RTS caught up with Gilbert de Meuron, a descendant of the family, in canton Neuchâtel. He agreed to talk to us about his grandfather, between admiration for his entrepreneurial talents and embarrassment about the origin of his fortune.

“It’s a bit tragic to imagine that the exploitation of human beings was something normal for some people.” He acknowledges the presence of slaves in his grandfather’s factories, although he doesn’t know how many there were or how they were treated. “We don’t know much more than that”.

Auguste de Meuron devoted part of his fortune to building the psychiatric hospital in Préfargier, in canton Neuchâtel. For Gilbert de Meuron, Chairman of the Préfargier Foundation, his grandfather gives the impression of “a personality who was humane, who would perhaps have found it difficult to treat people like slaves”. “But we’d really like to have the whole story so that, once and for all, we can paint a fair portrait of Auguste Frédéric de Meuron

He goes on to say that “before we can talk about reparation, we really need to know the truth. Because without that, we’re just making plans.”

What is “dialogue”?

The aim of this editorial offer is to encourage dialogue between the different regions of the country, without language barriers.

Translated by DeepL/amva

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.