The Swiss textile industry’s unsavoury past

A Zurich exhibition looks at how the slave trade, colonial exploitation and religious conversion all led to the establishment of Switzerland’s textile industry and boosted its wealth.

In the 17th century, “Indians were the only ones who knew how to make printed cotton fabrics,” says Pascal Meyer, curator of an exhibit on textiles called “Indiennes”External link at the Swiss National Museum. “There was no cotton or colour in Europe.”

As the Zurich exhibition explains, the technique for manufacturing colourful printed cotton fabrics was copied by the Dutch and British who used mechanisation to make them cheaper and undermined the Indian textile industry. The bright and affordable “Indiennes” fabrics produced in Europe became so popular that the “Sun King” Louis XIV had to ban them due to pressure from domestic wool, silk and linen manufacturers.

Swiss boom and the slave trade

Protectionism can have unintended consequences, and France’s 17th-century ban on the manufacture and import of Indiennes was a godsend for Switzerland. French Protestants, who were also fleeing religious persecution, emigrated to Switzerland and established textile factories near the French border in places like Geneva and Neuchâtel. The demand for these bright and affordable Indiennes was at its peak and the fabrics were smuggled across the border to France. In 1785, the Fabrique-Neuve factory in Cortaillod, Neuchâtel became the largest producer of Indiennes in Europe, churning out 160,000 cloth panels that year.

The trade in Indiennes brought enormous wealth to Switzerland, but it had a dark side. The fabrics were used as a kind of currency to be bartered for slaves in Africa who were then shipped to the New World. For example, Swiss fabrics made up 75% of the value of goods in a ship called Necker heading to Angola in 1789. The textile companies also invested their wealth in the slave trade. Records show that between 1783 and 1792, Basel-based textile firm Christoph Burckardt & Cie held shares in 21 slave ship expeditions that transported around 7,350 Africans to the Americas. Much of the prosperity in Swiss textile hubs around Geneva, Neuchâtel, Aargau, Zurich and Basel was linked to the slave trade.

Colonial project

The origins of Switzerland’s status as a top commodity trading hub can be traced back to the mid-19th century when Swiss merchants bought and sold goods like Indian cotton, Japanese silks and West African cocoa all over the world. These commodities never reached Switzerland, but profits from their trade ended up in the country.

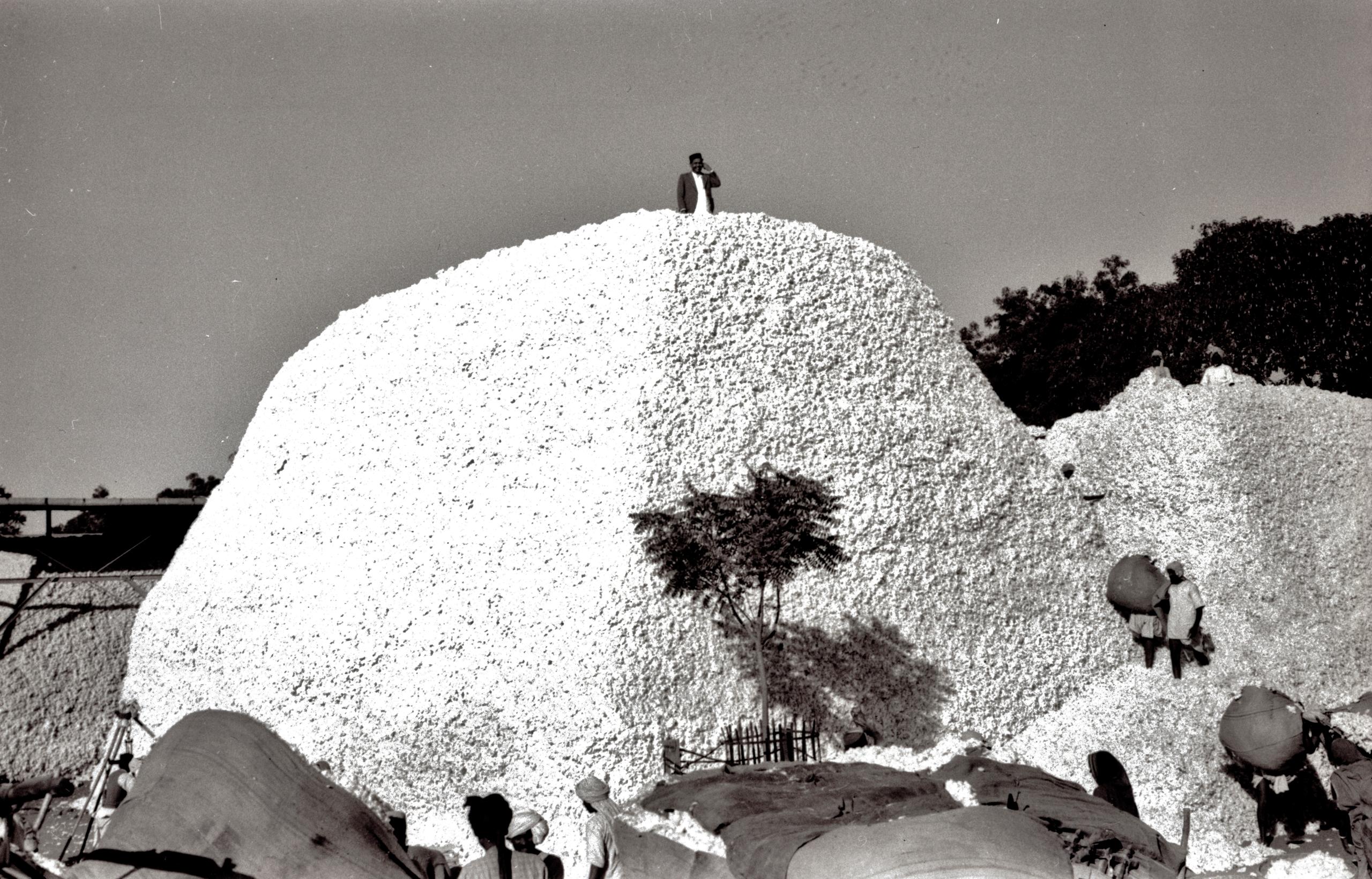

The American civil war and subsequent abolition of slavery created a commodity crisis in the 1860s, especially for cotton. Swiss firm Volkart, which had been operating out of India since 1851, made raw cotton its main business. It took advantage of Britain’s colonial interests in supplying textile mills in Manchester to expand its operations in India.

Under British colonial rule, Indian farmers were coerced into growing cotton instead of food crops and had to pay a land tax that went directly into the British Raj’s coffers. Thanks to these policies and expansion of the railway to India’s interior regions, Volkart was able to commandeer 10% of all Indian cotton exports to Europe. The central location of the Swiss city of Winterthur, where Volkart was based, meant that the company was able to supply spinning mills in northern France and Italy, Belgium, Ruhr in Germany and the rest of Switzerland.

While Volkart’s employees were asked to renounce racial prejudice, they followed some of the practices of colonial rulers in India.

“Indian employees were not allowed to enter their break room. It was also a colonial style of living and working with Indians,” says Meyer.

Missionary zeal

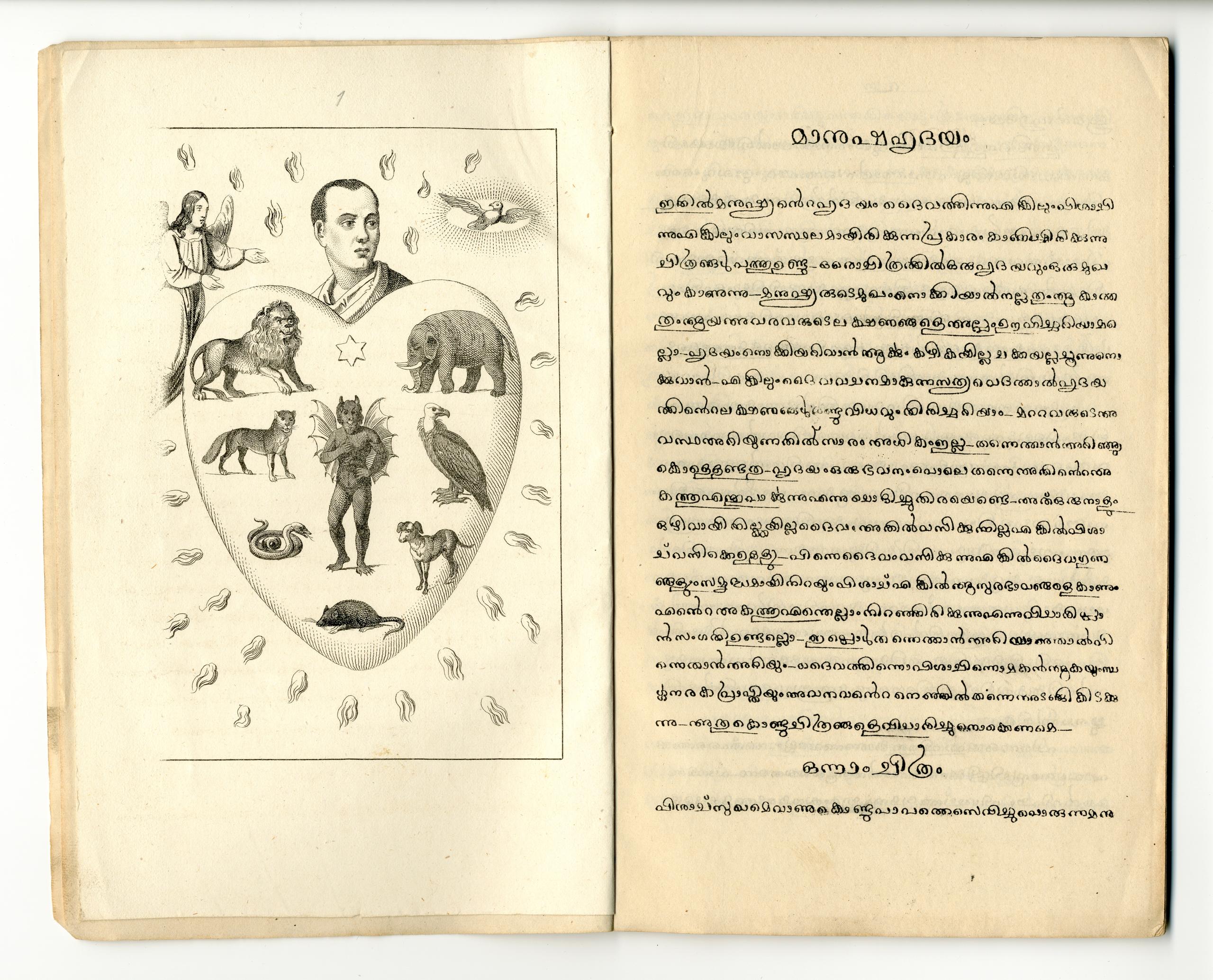

Another venture that flourished during colonial rule was the Basel Mission. Founded in 1815 by Swiss protestants and German Lutherans, it sought to convert “heathens” – non-believers – to Christianity. The effort was quite successful in what are now the southern Indian states of Kerala and Karnataka, particularly among Indians from the lower rungs of society who received access to education and training for the first time.

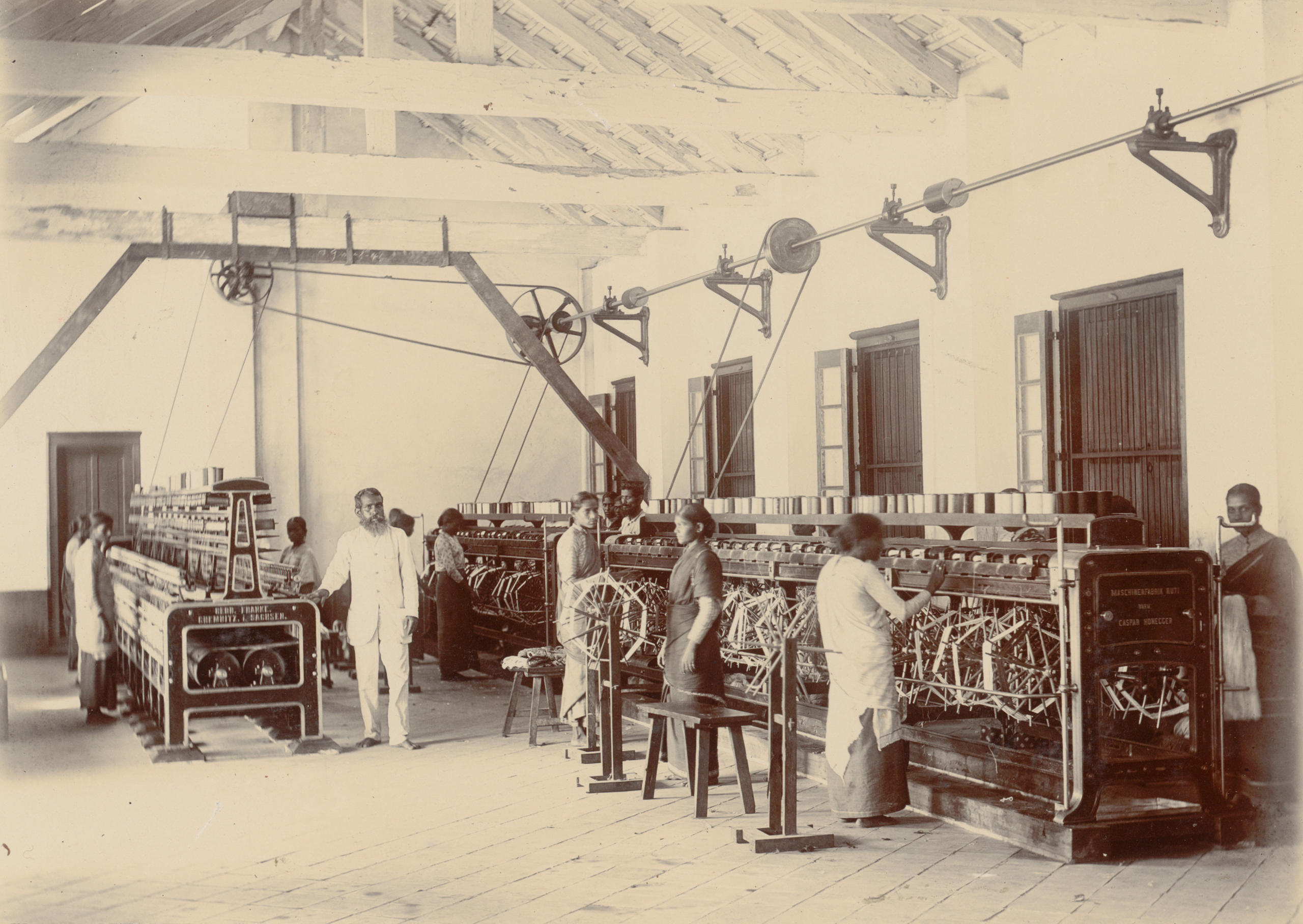

However, conversion to another religion meant risking being shunned from the community and losing a livelihood. The Basel Mission responded by starting commercial projects in India such as weaving factories to employ the newly converted. By the 1860s it ran four weaving mills and exported textiles to far-flung corners of the British empire like Africa, the Middle East and Australia.

“Part of the mission was good because they provided jobs for Indians, but part was colonialist as they only helped those who became Christians,” says Meyer.

The goal of the “Indiennes” exhibition at the National Museum is to show Swiss people how their country and its textile industry is connected to world history and colonialism. And the industry still has many challenges to contend with, Meyer says.

“We have a lot of workshops with young people to discuss issues like fair trade and fast fashion.”

Information source: “Indiennes: Material for a thousand stories” published in 2019 by Christoph Merian Verlag and edited by the Swiss National Museum.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.