Is bunker housing for asylum seekers at tipping point?

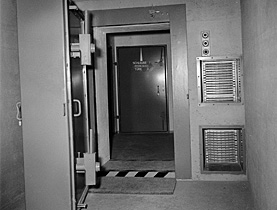

After fleeing repressive regimes and risking their lives to get to Switzerland, the last place asylum seekers imagine ending up is an underground nuclear bunker. It’s an increasingly common, drastic step taken by overburdened cantons.

As the autumn sun slowly sets over Lake Geneva, some 200 people strike up a defiant chant.

“Stop bunkers! We need fresh air!”

Holding lit torches, the group – mainly asylum seekers from Eritrea, but also from Syria and other parts of Africa – slowly makes its way through the centre of Lausanne, stopping traffic and open-mouthed passers-by.

At the head of the column, two people carry their message: “We are not at war. Don’t house us in bunkers.”

Since August a group of asylum seekers based in canton Vaud, supported by half a dozen Swiss associations, have been fighting to improve the living conditions in their new homes – converted underground nuclear fallout shelters dotted across the region.

“I was shocked when I learned I was going to stay in a bunker. Eritreans have family members who have been imprisoned underground so there is a bad connotation,” said Hussain*, an Eritrean who has been living for four months in a civil protection shelter in Lausanne.

The 28-year-old is one of 400 asylum seekers housed in eight underground shelters run by the cantonal Vaud Establishment for Migrants (EVAMExternal link). In each, 50-60 migrants sleep together in collective dormitories without windows and with limited privacy. They have to leave their bunker every day at 10am and only return in the evening. The average length of stay varies from a few months to a year.

Health impact

Under such conditions their mental and physical health have deteriorated, say NGOs supporting their protest.

“I can’t sleep at night. It’s always noisy and the scabies I caught in Libya itches terribly. I was treated for it, but as the bunker is very dirty I caught it again. At night I can’t stop thinking about prison and the desert. I feel terrible,” said Efrem*, aged 19.

Exhausted by the living conditions, the protesters want to change accommodation and move above ground.

“For the moment the only way to get out of the bunker is to get a health problem,” said Ibrahim*.

In the short-term the group says the shelters should be open 24hrs a day. They also want access to a kitchen and a reduction in the number housed in each shelter. They say their demands made in writing to the president of the cantonal government and to the head of EVAM have had little impact.

Pierre-Yves Maillard, the Social Democrat president of the Vaud government, said members were “aware of the these requests and taking them seriously.” A forthcoming debate is expected in the Vaud parliament.

More

Vaud struggles to provide housing for asylum seekers

In Switzerland the federal authorities are responsible for asylum proceedings but it is up to the country’s 26 cantonal authorities, which enjoy considerable autonomy, to implement the policy and oversee questions such as accommodation.

The details of what should be offered is open. Article 12 of the Swiss Constitution states that “persons in need and unable to provide for themselves should have the right to assistance and care, and to the financial means required for a decent standard of living”.

In December 2013 the Federal Court rejected a complaint from a 34-year-old asylum seeker wanting to be transferred from a Vaud fall-out shelter. According to Switzerland’s highest court, spending a night in a collective accommodation is not degrading or “against the minimum requirements” of the constitution.

While asylum seekers do not have the legal right to choose their living quarters, the Swiss Refugee Council says cantons are responsible for ensuring housing is “appropriate”.

Faced with a recent increase in the number of asylum seekers in Switzerland, principally from Eritrea and Syria, the communes, cantons and migrant bodies across the country have been struggling to find appropriate accommodation. Many have resorted to converting old buildings, schools and disused air-raid shelters or even more radical short-term solutions (see video).

More

A short-term solution to a refugee housing crisis

With eight bunkers in operation and potentially more in the pipeline, Vaud is using underground housing more than other regions. Geneva recently opened a second bunker, canton Bern has five, canton Neuchâtel two and canton Fribourg one. Jura and Valais manage to do without bunkers.

Officials at EVAM say unfortunately they have to work with the reality on the ground: a sharp increase in numbers and a local shortage of housing.

“Asylum seekers and applicants who have been rejected shouldn’t be housed underground, but we prefer that than to let people sleep on the streets,” said EVAM spokesperson Sylvie Makela.

“Vaud is one of the cantons that receives the most asylum seekers – 8% of the total number who file requests in Switzerland – and Vaud is also one of the cantons where the lack of housing and apartments is the most acute. We are subject to the housing market laws and lack of apartments just like everyone else.”

EVAM says it is constantly seeking housing solutions, but unfortunately it remains difficult to find empty buildings, unoccupied apartments or land to build on and so there is little choice but to use nuclear shelters.

Beat Meiner, secretary general of the Swiss Refugee CouncilExternal link, is critical of their overuse, however. “We are not moles. We need fresh air and light. Humans are not made to live underground,” he commented. “Whereas for rejected adults, bunkers might be a solution, for asylum seekers this is completely unacceptable. Exceptionally, if there is no other way to prevent them becoming homeless, the bunkers may be used as a temporary solution for a very short period of time. In general we should try to avoid using them.”

Lausanne lawyer Jean-Michel Dolivo, who supports the demonstrators and who lodged a formal question on the issue at the Vaud parliament, felt the use of bunkers was symptomatic of a generally tougher line towards asylum seekers.

“The aim of Swiss asylum policy is not to welcome people but to send them back as fast as possible. If they live in poor conditions it will put pressure on them to leave,” he added.

Makela accepted that housing asylum seekers underground was perhaps not aiding Switzerland’s humanitarian image. “But at least we are housing them somewhere,” she declared, adding that the attitudes of local communities were not helping their task to find other options.

“Every time we propose to local communes to build accommodation to house asylum seekers the local population opposes,” said Makela.

*name withheld

The number of new people requesting asylum in Switzerland between January and September 2014 stood at 18,103. These included 5,721 Eritreans, who are the biggest group ahead of Syrians (3,059) and Sri Lankans (845).

From the beginning of January to the end of September, 140,000 migrants reached southern Italy by boat, most arriving from Libya. Half came from either Eritrea or Syria. This compares with 43,000 for the whole of 2013.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.