A special school for special needs

At eight years old, Manarekha still has difficulty speaking and counting. She has a learning difficulty that is not always easy for her adoptive family to deal with. They are helped by a pioneering school in the Italian-speaking southern Swiss canton of Ticino.

“Let’s see who can finish their milk first, OK?” Manarekha looks up at her father, his eyes still full of sleep. “Hurry up, the bus is arriving soon. Drink up, then we’ll brush our teeth.”

It is 7am and the Di Costantino-Laudi family is gathered at the breakfast table in their little villa in Vacallo, a town near the Italian border. Mother Babita, father Massimo, teenage daughter Iris, little Manarekha.

A multidisciplinary team

Launched in September 2017, the “welcoming class” project in Stabio is run with the participation of four teachers: Paola Klett Sala in the first grade class of 12 students; while Luca Canova, Patricia Castoldi-Ineichen, and Erika Guglielmo Ripamonti jointly manage the special school class, with eight students. The team is also accompanied by two interns.

Manarekha, eight years old with mischievous eyes, moves her legs under the table and tries to attract attention with her hands. “I’m going to school in a minibus,” she says. “First seat belt. Then music. It’s nice!” Her voice is melodious, but the words emerge jumbled. “Sometimes you have to be a bit creative to understand what she’s trying to say,” her mother explains.

Monny, as the family calls her, has a learning disability. “That is not a formal diagnosis,” her mother says. “We only know that our daughter learns more slowly than other children of her age and she needs special support at school.”

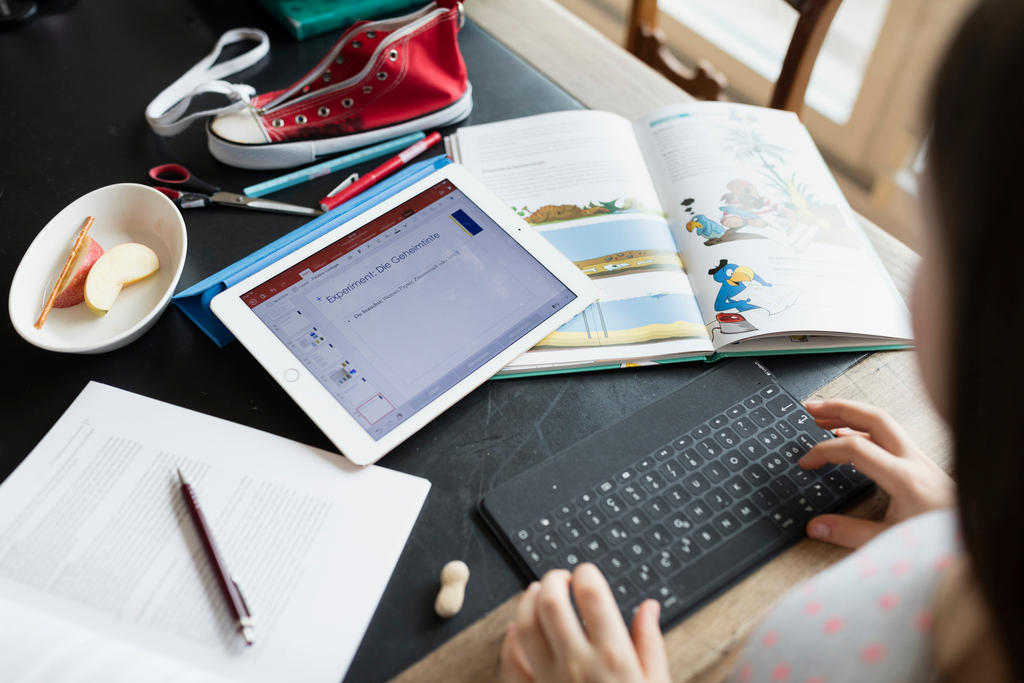

Manarekha has found this support at a special school in Stabio, some ten kilometres away, which this year launched a “welcoming class” pilot project. The eight children at the school with learning difficulties follow classes with first-year primary school pupils, according to their abilities.

Their parents think the experience is positive. “It’s good to know that she has teachers monitoring her in a specific way and that at the same time she’s in constant contact with other children,” says Babita. “And I have noticed that since she came into our family, Manarekha has continued to make progress.”

From India to Switzerland and back

Manarekha was born in southeast India and came to Switzerland in summer 2015 after an adoption process lasting nearly five years. Babita remembers with emotion their first meeting: the appalling conditions in the institution, the hopeful faces at the windows, and this little girl who was jumping up and down on the balcony.

“She had been described to us as a normal, tranquil child without any particular problems, but we realized at once that there was something wrong,” says Babita. In this isolated part of the enormous Indian subcontinent, their joy gave place to disbelief and then to concern.

Babita and Massimo planned to adopt her from the first time they saw her. “I too was adopted in India,” says Babita. “I had the luck to grow up here in Ticino, to study and be happy here. It always seemed right to offer that opportunity to someone else.”

But for Babita, the journey to India also had a deeper resonance. Only a few kilometres from Manarekha’s institution was the orphanage where she herself grew up. The family decided to visit it, and Babita was overcome with emotion when she found her name on an old register. “Parents: unknown. Destination: Switzerland,” it read. For this tiny woman in whom one senses great inner strength, it is as if one chapter has closed, just as another is about to open.

But Manarekha’s first months in Switzerland put the family sorely to the test. The little girl was rebellious, kicking, biting and yelling as if she were “a little animal in a cage”. She rejected 14-year-old Iris, now her sister. “She didn’t accept my presence and she got angry when I kissed Mum,” says Iris. “I felt excluded from my own family and that wasn’t easy to accept, especially because I had imagined things differently. I could only see the negative side. But later we managed to get on better.”

A childhood on the streets

Manarekha’s parents did not immediately realize their daughter’s learning difficulties, especially since she had been through deprivation and violence in her childhood which are not mentioned in any of her files but which she confided bit by bit to her new family. “She lived on the streets with other children, she didn’t get enough to eat and her body still bears the scars of the violence she suffered,” her mother says.

A year after she arrived in Switzerland, Manarekha was enrolled in elementary class in Vacallo, with other local children. Her Italian was not very good and she had trouble concentrating. At home in the evenings she always wanted her father to help with homework. “She always said she didn’t know anything,” says Massimo. “But she tried hard, she’s great!

On the advice of her teacher and the school director, Manarekha was subjected to a cognitive test. The result was clear: at eight years old her level was equivalent to a child of four or five. “So they suggested we put her in a special school,” says Massimo. “They expected an aggressive reaction, but we stayed calm and listened carefully to their suggestion. It was almost a relief to know that someone was ready to listen to our little girl.”

The canton of Ticino has been a pioneer in Switzerland for over 40 years in integrating pupils with learning difficulties. Inspired by the inclusive approach of neighbouring Italy, it has made it a priority. The project launched this year in Stabio, the school that Manarekha attends, nevertheless goes further by allowing a real exchange between the children and by providing teaching centred on the potential of every pupil.

More

A day at school with Manarekha

A daily struggle

But society is not always kind towards those who are different. Iris knows this well, as she is often faced with the merciless comments of her teenage peers about the children at the special school next door. “For me, it is not a problem to say that my sister is in a special school,” she says. “But I avoid saying it spontaneously. People don’t understand, they think these children are strange.”

Strange, no, but different, yes. For, as the coloured inscription in Manarekha’s classroom says, “We are all equal and all different”. The project in Stabio is perhaps a first step towards helping children to be more aware of this in future.

The Di Costantino-Laudi family has decided not to think about that for the moment, since the present is already full enough of unexpected things, obstacles big and small to be overcome. The most important thing for the moment is that Manarekha acquires a certain independence to help her in the life ahead.

Translated from Italian, swissinfo.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.