The Indian beauty on the Swiss watch

Her portrait has remained a mystery for almost 80 years. Could she be the royal who last ruled a small state that is today a part of India?

“We refer to the watch as ‘the Indian beauty’ because we haven’t been able to exactly identify the person represented on the enamel potrait,” Marc-André Strahm, antique watch expert at Swiss luxury watch brand Jaeger-LeCoultre, told swissinfo.ch.

The headquarters and production facility of the 182-year-old watch company is located in the sleepy little Swiss town of Le Sentier in the Jura mountains. It is part of the famous Vallée de Joux, which is widely regarded as the birthplace of Swiss watchmaking. The imposing Jaeger-LeCoultre complex dominates the rural skyline. At first glance, there is no indication that the utilitarian buildings house an unsolved mystery with an Indian connection.

But hidden inside the bowels of the Jaeger-LeCoultre complex lies a museum that pays homage to some of its most exquisite timepieces from the past. All the ornate watches and clocks displayed in the museum are described in detail except one – the so-called “Indian beauty”, which dates back to 1936.

More

The Indian Beauty

swissinfo’s interest in this watch was sparked by an idea for a story that would explore the links between Indian royalty and Swiss watchmaking. The so-called “Swiss period” that spanned from 1890 to 1947 was when Swiss timepieces dominated the Indian market.

They were more affordable than British watches but also offered rich clients the opportunity to showcase their status through ornate work such as fine engraving and enamel portraits – something that was much appreciated by Indian royalty. Many Indian maharajahs commissioned fancy pocket watches that boasted a combination of complicated watch movements and elaborate cases featuring jewels and self-portraits in enamel.

More

The Maharaja watch

While researching Swiss timepieces commissioned by Indian royalty the Jaeger-LeCoultre Indian beauty watch cropped up. It stood out because it featured a portrait of an Indian noble woman – a rarity as most watches were adorned with portraits of maharajahs. This, plus the fact that the lady’s identity is still a mystery after almost 80 years, kicked off an investigation into her origins. But it would prove to be a hard puzzle to piece together.

Needle in a haystack

Purchased in 2004 by Jaeger-LeCoultre for a sum of US$77,526 (CHF77,391) at an auction, the identity of the woman on the back of the watch case still remains a mystery.

“The watch was bought in the 90s by a Lufthansa captain in Mumbai,” Stefan Muser of the Mannheim-based auction house Dr. Crott told swissinfo.ch. “Unfortunately at that time we did not have much information about this particular Reverso.”

With not much to go on, the only course of action was to sift through hundreds of vintage photographs of the various Indian royal families from that period. Not an easy task considering there were over 500 Princely States in British-ruled India.

To add to the difficulty, there were several glamorous princesses and queens from the period to choose from. While previous generations of female royals were confined to the royal palace, this new breed of blue-blooded ladies travelled around Europe buying the finest jewellery and attending the most talked-about parties. A few notable examples were Princess Gayatri Devi of Jaipur, who was ranked among the ten most beautiful women by Vogue magazine, and Princess Sita Devi of Karputhla and Princess Sanyogita Bai Holkar of Indore, who were muses for famous photographers like Cecil Beaton and Man Ray.

Could one of these dazzling royals have served as an inspiration for the mysterious woman on the watch?

The last queen

The hunt finally led to the tiny state of Tripura in north-eastern India. Around a quarter the size of Switzerland, the state is home to the over 600-year-old Manikya dynasty of rulers. Even though Tripura became a British protectorate in 1809 under colonial rule, the Manikya maharajahs were still recognised as sovereign rulers.

However, Tripura ceased to be a kingdom soon after India gained independence from the British. Interestingly, the last royal to rule Tripura was a woman. The death of the maharajah of Tripura Bir Bikram Kishore Debbaraman in 1947 – he built Tripura’s only airport – meant that his son Bikram Kishore Debbaraman became the de-facto ruler overnight. However, since he was only 14 years old at the time, his mother Kanchan Prabha Devi took on the responsibility of ruling in his name as the Regent and ran state affairs from 1947 to 1949.

And she is the most likely candidate for the mystery woman whose portrait adorns the Jaeger-LeCoutre Indian beauty watch.

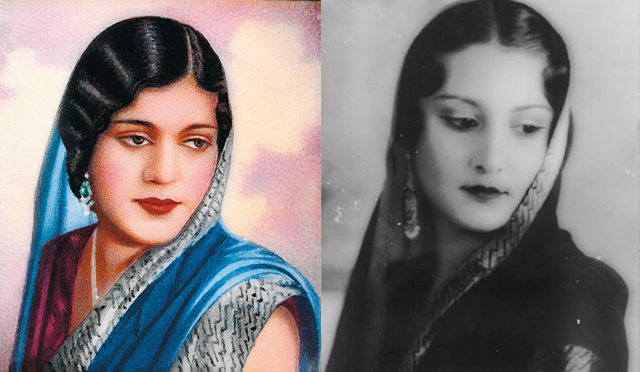

Prabha Devi’s likeness to the portrait on the watch is remarkable, especially the pose, hairstyle and the zig-zag pattern of the saree she is wearing. It very likely that the artist painted the portrait using the same photograph, as is the practice even today.

Her grandson and current head of the royal house of Tripura, 38-year-old Pradyot Debbaraman, confirmed to swissinfo.ch that the black and white photograph did indeed belong to Kanchan Prabha Devi.

“There is a very strong resemblance between the portrait on the watch and the photograph of my grandmother,” he told swissinfo.ch.

However, he is not 100% certain they are the same and plans to contact relatives and search the family archives for more information.

Born in 1914, Kanchan Prabha Devi was the eldest daughter of the Maharajah of Panna and became the second wife of the Maharajah of Tripura on her 17th birthday. It was she who signed the merger of Tripura with the Indian union on October 15, 1949 that signaled the end of monarchy.

“It is my desire that, as early as conditions permit, steps will be taken to set up a constitution-making body representative of all sections of the people…,” Prabha Devi said in a proclamation on the administration of Tripura.

“She is a very important person in the context that Tripura was the only state in the north-east to willingly merge with India,” says Debbaraman.

As Regent she faced a serious test when India was partitioned after independence in 1947. The Hindu-dominated West Bengal province became a part of India while the Muslim-dominated East Bengal (later to become Bangladesh) joined the newly created country of Pakistan. Tripura faced a significant refugee influx of Hindus fleeing bordering East Bengal and the state risked being involved in a tug-of-war between India and Pakistan.

“A strong well-organised internal security force has to be build up, the finance of the state have to be rehabilitated, a scheme of road construction to provide internal communications as well as direct link with the Indian union has to be put into effect, supply of essential commodities of which there is an acute shortage have to be made available to the people, and the machinery of the government has to be general, tightened up,” she stated.

As the last ruler of Tripura, she did an admirable job in safely steering it through the perilous transition from independent kingdom to a part of the Indian union with a democratic government. She died in 1973.

The Indian beauty watch is a Reverso, one of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s most popular watch models. In 1930, Swiss businessman César de Trey was visiting British-ruled India. At the end of a game of polo he was approached by a distraught player whose watch lens had broken during the course of the match. He entreated the Swiss visitor to come up with a watch that could withstand the rigours of polo. De Trey had recently become a distributor for his friend Jacques-David LeCoultre’s high-end Swiss watches.

The Swiss businessman outsourced the challenge to engineer Alfred Chauvot who came up with a solution one year later and filed a patent for “a watch able to slide in its cradle and swivel over completely”. They turned to Jacques-David LeCoultre to produce the aptly-named Reverso watch commercially.

Besides its obvious role in protecting the watch from damage, the flipping dial system of the Reverso also allows the case back to be personalised through engravings. This was a unique selling point at the time because the utilitarian wristwatches lacked the artistic flair of fancy pocket watches.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.