V-Cableway: Grindelwald’s construction controversy

The Jungfrau Region is a tourist area attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors each year, to ski, to hike or just to gawk at majestic mountaintops. Alpinist Dan Moore writes that a large-scale development project could mean the death of the last vestiges of the untouched landscape surrounding the world famous Eiger North Face.

Construction of the V-Bahn (or V-Cableway) project is well underway in the area. When completed, the two new cableways will start from the same valley station then lead off up the mountain in different directions, hence the V.

One will replace the out-dated Männlichenbahn, and a second, the “Eiger Express”, to cart tourists faster than ever before up to the Jungfraujoch – a mountain station that is a tourist magnet due to its lofty position at the top of the Alp’s longest glacier.

But ‘Far away …from ordinary’. I pause the V-Cableway’s advertisement video and read the words again.

You’d think that a project expected to cost half a billion Swiss francs, and which is largely catered towards foreign tourism would have the scope to employ a good translator.

This claim, slapped on the side of every cabin of the new Eiger Express, seems to confuse two distinct notions: away from the ordinary(noun); which gives a positive feeling of escape, and far from ordinary(adjective); which sounds to me more like “just a bit weird”. Assuming they meant the former, is it even true?

The new “Grindelwald Terminal” station from which both journeys will begin is neither a terminal station nor actually in Grindelwald. In fact, when it opens it will eliminate the need to visit Grindelwald all together. A better title then would be the “Grindelwald Bypass”.

Construction of the station began with the digging of a giant crater, larger than a football field, which was eventually filled in with concrete. Metre after cubic metre was pumped into the ground; an endless line of trucks waited their turn. And each time I journeyed in or out of the valley, I’d look down at the site to see it seemingly double in size.

The Grindelwald Terminal is to be fully heated and will include a shopping centre and car park. Future visitors need not have any contact whatsoever with the outside world on their journey from home or hotel to the fully enclosed Jungfraujoch tourist facility high above.

The same is true of the new Eigergletscher station – the highest point for skiers and where visitors heading to the Jungfraujoch will have to change onto a train for the last part of their journey. Whereas before you could get out at Eigergletscher, step onto a restaurant veranda and feel the icy breath of the glaciers around you; look up at the grand north face of the Mönch and feel the power of all that rock and ice, now you may only peer out from a warm bubble through panes of glass. It seems that once complete – at least for tourists travelling to the Jungfraujoch – the sense of hearing, smell and touch and the feel of the rarefied air will be lost. They might as well be travelling inside a vacuum tube.

But how will things change for hikers, skiers or alpinists who truly want to experience the mountains, and not just look at them?

The ‘White Hare‘ is a local name for one of the last hidden freeride ski spots in the area. Just a ten-minute traverse on skis from the groomed slopes, around a small hillock and you are often completely alone, hidden in silence. It’s not exactly a secret, but it’s always quiet there.

The great amphitheatre of the Eiger’s north face stands over you. Just ahead, rising up at a near constant angle to meet its base is a broad field of glistening powder, which, thanks to its position, is never touched by sunlight. It is an accumulation of all the snow that has roared down the face during foehn storms and resultant avalanches. The slope is invariably untouched.

When the new cables are slung however, and the glass bubbles strung beneath it, the Eiger Express will carry passengers directly over the White Hare, almost parallel to the north face itself. Any skiers gazing out will spot the first tracks in the snow, and race to make their own.

Perhaps more disturbing for me, as a local alpinist, is the fact that this winter will be the last chance to climb the classic Heckmair route on the Eiger, or any other route on its north face for that matter, without eyes burning into the back of you, closer than ever before, distracting you; hands waving, seemingly so close as to grab at the cuffs of your trousers.

Also, when the snows are gone in spring, the first half of the famous Eiger Trail will be completely visible to the masses riding the cable car, and therefore will no longer be the awe-inspiring hike it once was.

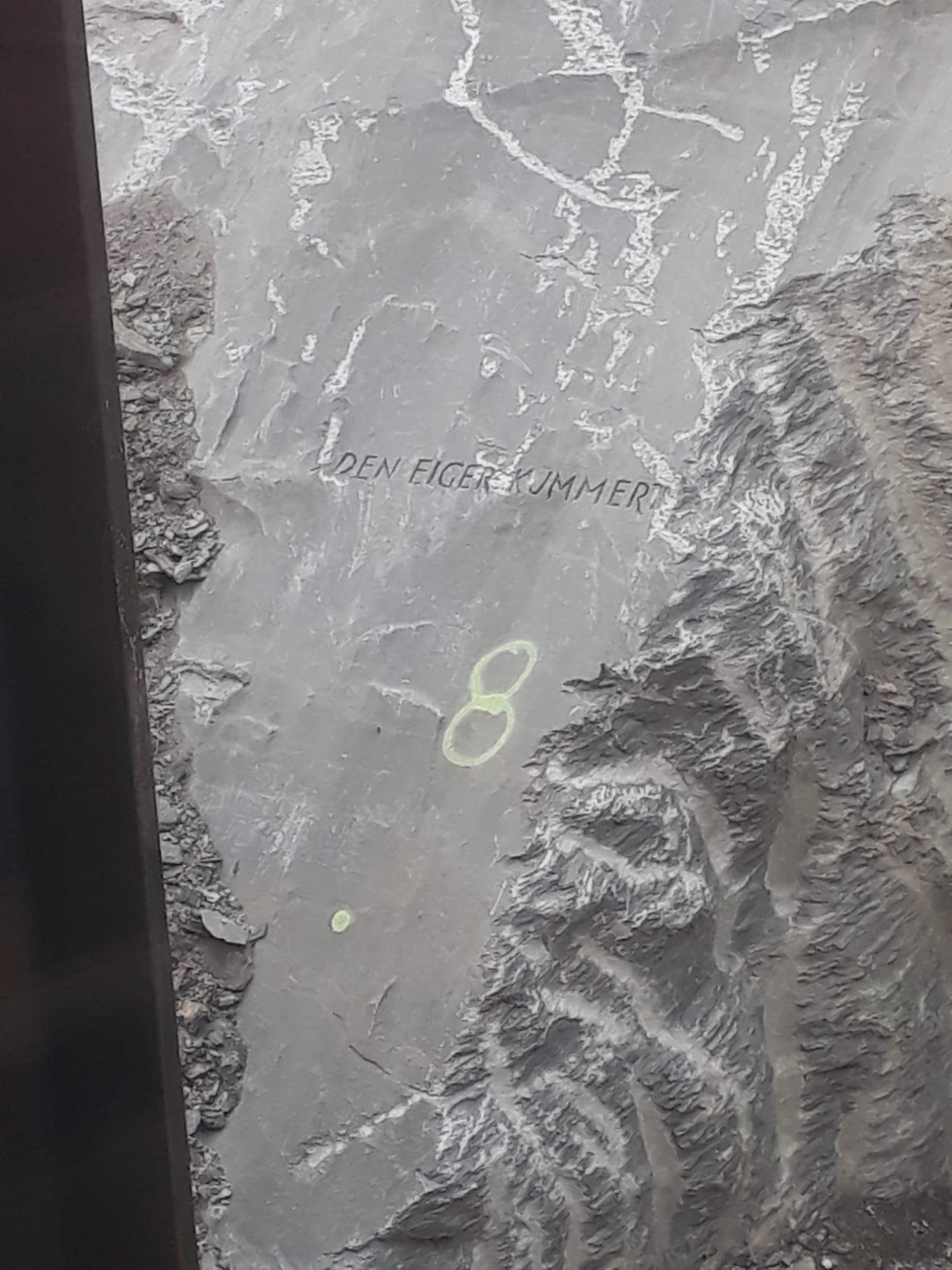

A few years ago, local mountain guide and stonemason Hannes Stähli was asked to chronicle the history of mountain guiding in Switzerland with special regard to the Eiger, and, with hammer and chisel, inscribe that history into the rocks along the Eiger Trail. If you walk the trail in full, starting from Grindelwald, you can read these short and interesting snippets of history in chronological order.

One final short statement he inscribed was to be found on the Rotstock, near the old Eigergletscher station. It read, “Den Eiger kümmerts nicht”, which translates as “the Eiger doesn’t care”.

It is, I think, a statement about the arguable indifference of the natural world to much of man’s activity; a reminder to me of just how small and unimportant we humans are, even when compared to a single, majestic mountain. Despite the fact it’s slowly crumbling, the Eiger was here thousands of years before us, and will be here thousands of years after we have left.

In 2016, before building work began, a short article in a local newspaper was written about this very inscription. It argued that all debate about the V-Cableway – whether it has tall masts or short, whether the route be diverted and have a middle station in order to reduce the visual impact of running so close to the north face, etc. – was anathema to the Eiger itself.

Fast forward to the winter of 18/19 and the irony of what happened to this inscription is self-explanatory. As they chipped, drilled and blasted the first of two massive, new tunnels through the Eiger’s western foot to house the cable car infrastructure at the top, the sentence was inadvertently cut short, and for several months read, “Den Eiger kümmerts” … The Eiger cares.

When I discovered the tunnels last winter, I could barely believe how fast they’d been made. I had this sense that they gave the mountain no time to adjust; that they had stirred a giant from its slumber.

Over 100 years ago, the original tunnels for the trains heading to the Jungfraujoch were built using handheld pneumatic chippers and pickaxes, taking over 14 years to complete. It was a pioneering effort; work conditions were atrocious; people lost their lives… These two had been blasted through in a matter of weeks.

I’m not saying that we should go back to the old ways; that people should risk their lives. It is incredible now just how fast, efficiently, and safely we can progress through major engineering works. And it’s good to know that with modern safety measures and equipment, workers are more or less guaranteed to return home safely to their families after a hard day’s work.

But it is also scary now just how fast things can be done. As technology continues to race ahead, enabling us to complete projects faster, are we not at risk of entering an exponential paving over, and digging through, of the natural world?

I had gone up with a climbing partner to sleep at the Eigergletscher hotel, intent on repeating the climb we made on the north face back in 2016. But sleep eluded us. Machines whined and buzzed away all evening. Giving up, I stepped outside and was greeted by the luminescent rays of floodlights reflecting off yellow machinery and rock dust in the cold night.

It had been a strange week on the Eiger. Another party had turned back a few days earlier at the section known as the Ice Hose. The weather forecast for us was not inspiring: Mists hung in the air; a cold wind blew from the north. It was to be the only day of bad weather in over three weeks. Conditions on the face itself were hard too. We decided to bail out. Besides the weather, something just felt wrong. It simply wasn’t the right time.

Two days later, two of the strongest alpinists I know went to climb the same route. One of them, we will never know why, took a fall while leading high up on the face. Though the pair were roped up, the distance he fell was great, and he died of his injuries on the spot. We saw the helicopter from down in the valley. We couldn’t believe it.

In hindsight, this felt like a tragic ‘finale’. And a deep feeling grew in me: that the Eiger was currently angry at mankind. When we climbed the route in 2016, it was pure serenity. I felt wrapped in the arms of a caring mother as we moved through that majestic space. The Eiger had shown its softer side then; its feminine side. Now it seemed, the masculine malice of all the folklore was stirring once more.

Spookily during that time, the shortened sentence, “the Eiger cares”, remained chiselled into the wall. A few weeks later, when they expanded the tunnel further, the remaining words were lost too.

Beyond bias

Now you’d think I am fully opposed to the V-Cableway’s existence; that I have good reasons for being so.

Let me put it this way. I am no more against the building of one new cable car, despite it being in my backyard, and despite it visually impacting the view of the most important mountain in the world to me, than I am against the building of any new highway, industrial unit, power plant or superstore on any previously virgin piece of land.

Though the Eiger Express does travel over short sections of previously natural landscape, it has sprung up in a region that already has 62 operating ski lifts, including cable cars, chairlifts and drag lifts; a region that is already packed so full of skiers in high season that you cannot actually ski at times; a region through which over 1,000,000 (yes, a million) tourists passed in 2017 on route to the Jungfraujoch. So the new infrastructure is not exactly out of context.

Once a modern cableway like this has been built, it should be able to run for a minimum of 50 years. Though its construction has a major environmental impact, as well as a big carbon footprint, the physical side of this only lasts around two years. After that, aside from general maintenance, it only needs electricity to run, most of which will come from long-established hydroelectric plants in the region.

In the long term, a new cable car system here is unlikely to have any significant impact on wildlife. They are relatively quiet, and move high above the ground at a slow, constant speed. Furthermore, since the idea of the Eiger Express is to shift visitors to the Jungfraujoch from the existing, slow-moving trains, it will mean firstly, that fewer trains are likely to run, which would reduce noise pollution in the valley and secondly, that the trains are less crowded.

Over the last few decades, local people have been increasingly put off riding the trains because of their sardine-like nature. Now, with the possibility of actually getting a seat, might they not be tempted once more to visit the area and its restaurants, and go hiking?

We might even start to see the separation of the two kinds of tourists; those riding to the Jungfraujoch and back down again as fast as they can, and visitors taking more time, riding the slow train and getting out to stroll in an alpine meadow.

It’s impossible to say what knock-on effects the V-Cableway will have. There has been a lot of angry opposition in the local population. But that won’t change a thing.

Developments like the V-CablewayExternal link are a product of our society. We are to blame. It’s the cycle of supply and demand. If there’s a demand, and profits are high enough, then of course they are going to supply.

Despite my personal bias, and my deep connection with the mountains, can I really say I’m opposed to this project? The right-hand half of the V, an upgrade to the Männlichen cableway, was a long time coming. The journey previously was excruciatingly slow. With this, I have no qualms.

The strongest arguments against were regarding the visual impact of the left-hand branch, the Eiger Express, on the landscape surrounding the Eiger. But won’t the pain fade? In five or 10 years, won’t it also have become part of the landscape?

I asked a local teenager from Wärgistal, the area over which the Eiger Express will run, what she thought about the project. “Just terrible”, she replied. Then I asked if she’d use it to go skiing. “Of course”, she said, without hesitation. So will I, I thought.

And the next generation growing up in Grindelwald? For them it will seem to have always been there. For them it will be quite ordinary.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.