As glaciers shrink, are the Alps more dangerous?

The melting of the glaciers is destabilising mountain slopes and increasing the risk of landslides and flooding. Yet it is also opening up new opportunities for Alpine tourism.

It was a hot summer’s day, without a drop of rain. Local people were preparing their evening meal, while tourists enjoyed the mountain air as they walked among the picturesque Alpine houses. In ZermattExternal link, at the foot of the Matterhorn, there was no indication that the placid mountain stream flowing through the village was about to turn into a raging mass of water and mud.

More

Stream becomes a torrent in Zermatt

When the Triftbach suddenly burst its banks one day last summer, it did not cause loss of life, but it damaged housing and infrastructure. The start of it was the sudden outflow of an underground lake that had formed under a glacier above the tourist town in canton Valais, which the mayor of Zermatt, Romy Biner-Hauser, later called “an unforeseeable freak of nature”.

Forecasting events of this kind is “very difficult”, admits Christophe LambielExternal link, a geomorphology specialist and professor at the University of Lausanne. What can be predicted is that climate warming will increase the probability of such extreme events occurring. “Some Alpine villages are at risk,” Lambiel says.

From the top of the Alps right down into the valleys, this swissinfo.ch series explores the effects of the melting of glaciers at different altitudes, and the strategies being adopted in Switzerland to try to cope with the problem.

3,000 – 4,500 metres: Alpine glaciers and the landscape

2,000 – 3,000 m: tourism and natural hazards

1,000 – 2,000 m: power generation

0 – 1,000 m: water resources

High temperatures, and especially long-lasting summer heatwaves, have increased the rate at which snow and ice are melting in the high mountains. As a result, decently sized lakes may form above, beside or underneath glaciers.

Thanks to webcams and satellite pictures, pools or lakes that form on top of glaciers can be adequately monitored. The lake called Les Faverges on the Plaine Morte glacier between cantons Bern and Freiburg, at an altitude of 2,700 metres, drains naturally each year. A warning system lets people know when the water level is starting to go down.

This animated picture shows how Les Faverges drains naturally:

Les Faverges is getting bigger year by year, however, and to prevent flooding in the village of Lenk below and in the Simmen Valley, an artificial drainage channel was recently dug. The same approach was taken ten years ago in the case of the lower Grindelwald glacier in the Bernese Oberland.

More

Birth and death of a glacial lake

For Lambiel, what is more worrying is bodies of water forming inside glaciers, hidden from view. Lakes underneath glaciers can contain tens of thousands of cubic metres of water, which are likely to burst out without warning if the water finds a way through the ice. “We become aware of their existence only when it is too late to do anything – which is what happened in Zermatt”, explains Lambiel.

To try to identify these hidden lakes using probes would be “too complicated and expensive”, Valais’ cantonal geologist Raphaël Mayoraz has told the newspaper Le Nouvelliste. There are alternative solutions, however: for one thing, use of geophones, which detect seismic waves and movements underground, and also sensors that measure the flow of mountain streams.

New lakes formed as a result of melting of glaciers are not just an added risk factor for natural disasters. The appearance of bodies of water on rock that used to be covered with glaciers also creates landscapes that may become a tourist attraction.

According to a studyExternal link published in 2014, the Swiss Alps may be getting hundreds of new lakes with a total surface of over 50 sq km. These glacier lakes “add value to the landscape”, the study found. Simple suspension bridges (like the Trift Bridge in the Bernese Oberland), “via ferrata” climbing trails and educational nature trails might become new attractions for people who enjoy being in the mountains.

Lakes up in the Alps with unpredictable behaviour are not the only hazard for villages, roads and infrastructure in the region.

“With increasing temperatures, what are called ‘hanging’ glaciers on very steep slopes are losing their grip, and may set off ice avalanches. We saw that happen in 2017 in Saas-Grund, Valais,” explains Lambiel.

The shrinking of glaciers, and especially the melting of the permafrost – the permanently frozen ground in the Alps above 2,500 metres – are destabilising the slopes of the mountains themselves. Masses of loose material may start to slide under the pressure of water building up in many parts of the Alps, warnsExternal link the federal government’s consultative body on climate change.

Safety of Alpine trails

The change in the Alpine landscape is a constant challenge for those who manage the Alpine chalets used by hikers and climbers. About a third of the 153 accommodation facilities maintained by the Swiss Alpine Club (SAExternal linkC) are near a glacier.

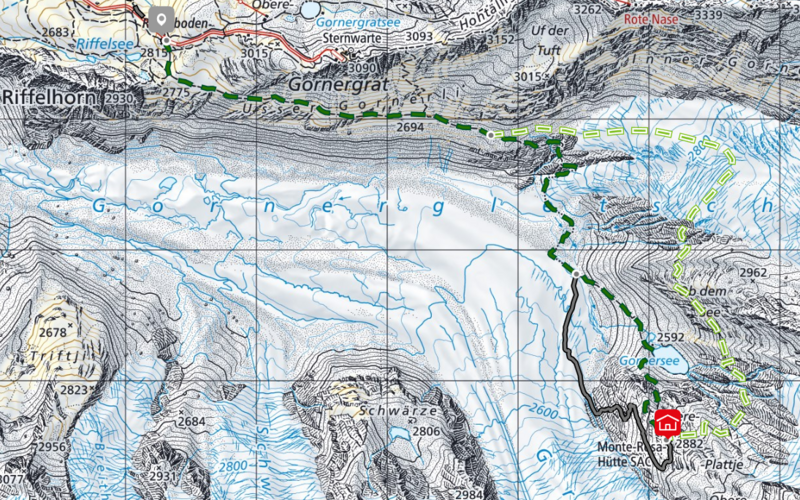

To reach the TriftExternal link chalet, which at one time could be reached on foot across the tip of the glacier, a simple suspension bridge has now been built, which attracts hundreds of tourists every year. Due to climate change, access to the Monte Rosa chalet has had to be completely rerouted. The new path is safer, shorter, and needs less maintenance, theExternal link SAC has found.

But where alternatives cannot be found, SAC members have been clearing the paths. For René Wyss, in charge of maintaining mountain trails, it’s hard and dangerous work on the mountain slope.

More

Rocks on mountain trails

More hazardous now?

Lambiel of the University of Lausanne, who is often out in the Alps, says he does not feel more of a risk than may have been the case in the past. Quite to the contrary. The hazards caused by glaciers are in his view “likely less” than they were 150 years ago. The reason for this is simple enough, he says: “The glaciers have gotten smaller, so there’s less ice.” He recalls some of the natural disasters of the past century, like in 1965 at the Mattmark dam in Valais, when 88 people died.

More

Remembering Mattmark

Caution in hot weather

“We know what the riskiest glaciers in Switzerland are,” says Lambiel. In Valais the ones to watch are the Trift and the Weisshorn, up above Zermatt.

And while Switzerland has one of the densest networks of measurement-taking in the world, with monitoring and early warning systems, the researcher still thinks people should be careful.

“We can’t control everything,” he says. “I would advise all Alpine hikers and climbers to be on the watch and take every precaution, especially in those periods of high heat.”

More

Glaciers and the changing landscape in the Alps

More

What we can learn from glacier-surfing turtles

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.