The long-lasting legacy of the Lebensreform movement

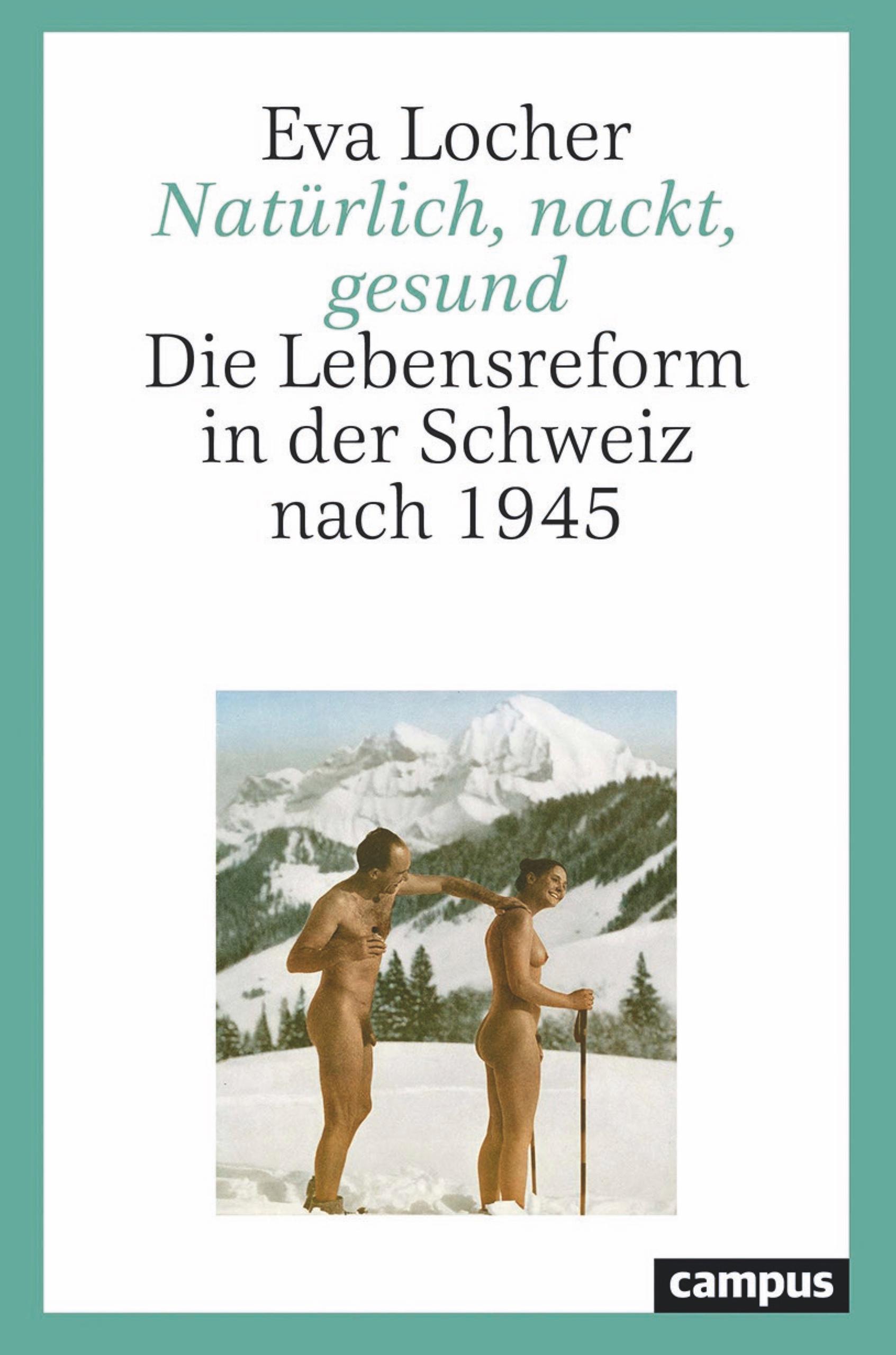

The nude skiing failed to catch on, but the influence of the Lebensreform movement is all around us – from saunas and almond milk to yoga and detoxing – explains historian Eva Locher in an interview.

When most people think of the Lebensreform (life reform) movement, they might think of people frolicking naked in canton Ticino, southern Switzerland, 100 years ago.

More

LGBT pioneer’s spectacular painting returns to Monte Verità

Yet the ideal of “living according to nature”, which is how the Lebensreform movement reacted to the mechanisation of life in Switzerland and Germany at the end of the 19th century, has had a lasting effect on several aspects of modern life: just about every restaurant offers vegetarian dishes, many people talk as a matter of course about detoxing their bodies, and alternative medical therapies are accepted by health insurers.

Limited for a long time to initiates, the ideas of the Lebensreform movement enjoyed a post-war boom that continues to this day. SWI swissinfo.ch asks historian Eva Locher about the continuing success of Lebensreform ideas.

SWI: Let’s start with a great Swiss invention, Birchermüesli. The son of its inventor said in 1964 that his father’s teachings were no longer seen as “an intolerable rejection of everything enjoyable” but were now an acceptable approach to healthy eating. What was so bad about these ideas before?

Eva Locher: The main issue was meat, which back then was a status symbol. When someone came along and demanded that people give up meat for health reasons and only eat raw food, shredded wheat and vegetables, it came as a bit of a shock.

SWI: Lebensreform ideas went beyond eating müesli and being a vegetarian, though. What did a life inspired by the movement look like?

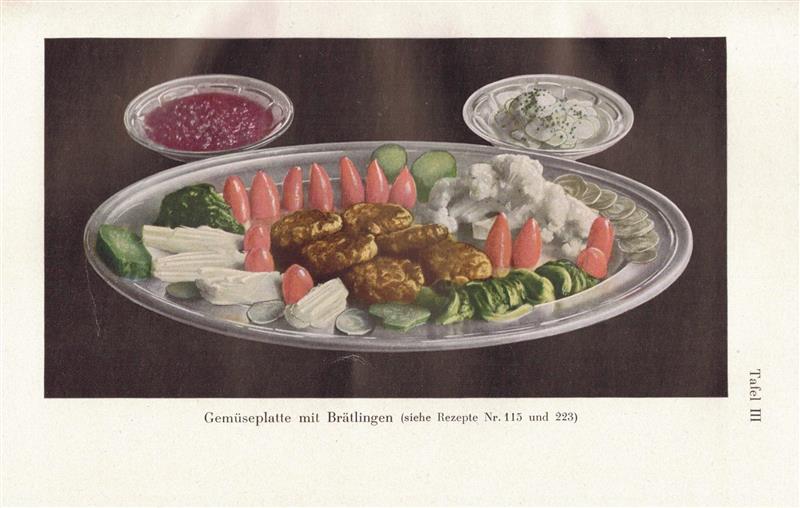

E.L.: Nutrition was certainly fundamental. All Lebensreform enthusiasts agreed that people should eat natural, unprocessed products as far as possible. You shopped at the health food store [known to this day as the “Reformhaus”] and spent a lot of your time in the kitchen, for the menus were a lot of work. Also there was a daily schedule, providing sufficient sleep and rest periods, which was dominated by the idea of moderation in all things. A person should not eat too much, should definitely not smoke or drink, and should be physically active.

SWI: What kind of physical activity?

E.L.: Lebensreformers went in for a whole range of sporting activities such as ball games, swimming and cross-country running. Dancing and gymnastics were important at first, but then yoga, with its breathing and relaxation techniques, became popular. The Swiss naturist federation also published numerous yoga textbooks and thus contributed to the spread of this activity in Switzerland. Today’s yoga studios are definitely a part of the Lebensreform legacy.

SWI: Where else can you see this legacy?

E.L.: In saunas, which were advocated by the naturopathic “Swiss society for public health” as a new health practice at the end of the 1940s. Today saunas are standard in every wellness hotel. A core legacy of the Lebensreform movement is definitely looking after one’s body, which most people do today, and the serious thought given to diet. Today every city has vegetarian restaurants. Almond milk, whole wheat crackers and soya products can be found in all the main supermarkets. Decades ago those were real niche products. The range of organically grown vegetables available today also goes back to these ideas. Lebensreform publications were already warning about “poison in our food” in the 1950s.

SWI: What kind of society did the Lebensreform enthusiasts envisage?

E.L.: The focus of their criticism of wider society changed over time. In 1900 they criticised mechanisation and urbanisation. After the Second World War it was more mass consumerism and the destruction of nature. But the individual was always the focus for change and improvement – only when every individual changes his or her lifestyle will society improve. That was the strategy right from the beginning: self-reform will lead to social reform.

SWI: What makes this belief system still attractive?

E.L.: The ideas of Lebensreform are particularly attractive to people who are ill or in a life crisis. The practices of Lebensreform promise self-empowerment: you know exactly what you need to do. These clear practices and procedures provide an anchor. Naturopathy in particular takes the view that human beings’ vital power gives them access to self-healing processes, so they can help themselves and their bodies.

SWI: So is everyone doing yoga or drinking almond milk really in the middle of a life crisis?

E.L.: No, of course not. Today the ideas of the Lebensreform movement are more likely to be linked to goals of self-improvement and self-optimisation. They are actually very compatible with the neoliberal view that everyone is responsible for their own welfare.

This is revealed in our willingness to monitor our bodies with fitness-trackers and watches that count our steps. The goal is to work on your body as much as possible. This urge finds its origin in the close monitoring of self and personal health advocated by the Lebensreform movement a century ago.

Responsibility for health is being increasingly delegated to the individual. If you get ill, it means you should have been exercising more and eating more healthily. The wider social context is conveniently ignored.

SWI: Despite this the Lebensreform movement attracted the interest of the alternative scene in the 1970s.

E.L.: Yes, but maybe not despite this but because of it! The post-1968 counter-culture was driven by a kind of strategic withdrawal, away from revolution and back to changing your own lifestyle. There was a turning away from the political, but also from consumerism. People went back to the land and lived in communes, grew their own food, preserved their vegetables and baked their own bread. It was called “counter-cuisine”.

Lebensreformers of an older generation realised that there was this interest among young people. They noticed that they were no longer being mocked as turnip-eating hippies and that the alternative scene and then wider sections of society were picking up on their ideas. By the mid-1970s they were suddenly part of the mainstream and were on committees with scientific experts. They were able to show that their theories had something to offer society.

SWI: For example?

E.L.: For example in anti-smoking campaigns, in organic farming, and in institutions like the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture, which still exists. But also of course in the whole area of environmental protection since the 1970s.

SWI: What ideas didn’t catch on?

E.L.: Nude skiing. Naturist clubs advocated light and air on bare skin. The light and air doesn’t get any purer than up in the mountains and in the snow, so it was decreed that people should ski in the nude. Although there are still nude hikers, hardly anyone today would think of going skiing without warm clothing.

Eva Locher is a historian and curator. Her bookExternal link, ‘Natürlich, nackt, gesund – Die Lebensreform in der Schweiz nach 1945’ (Natural, Naked, Healthy – The Life Reform in Switzerland after 1945), was published in 2021.

(Translated from German by Terence McNamee)

More

Naked hikers turn the other cheek

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!