The Swiss start-ups trying to change the way we eat

Start-ups are hoping to strike a fatal blow to Switzerland’s dairy culture. They say it’s time to change how we look at the food in our fridge. And the government agrees.

The lunchtime rush is about to start and restaurant manager Philip Gloor is practically running from one part of the kitchen to the next. On a weekday some 600 people eat at the Technopark start-up hub in Zurich. But there is at least one area in which Gloor can afford to relax today.

Pulling up a chair at his computer, he opens a report with the climate footprint of every ingredient used by his restaurant in the past month. It’s part of a new emission-cutting programme rolled out by his parent, the Compass Group (Switzerland). The tally shows Gloor outperformed other restaurants in the group, with his emissions 30% lower than the rest.

Compass wants to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 20%, and Gloor and Compass managers like him are assisted by Zurich food start-up EaternityExternal link. Run by three people in their 20s, Eaternity claim to have come up with the world’s first climate-friendly menu planning programme for restaurants. Compass is introducing it into 44 of their company canteensExternal link around the country. It adds up to a not insignificant part of the Swiss workforce able to opt for climate-friendly meals.

Every day one of the lunches offered by Gloor is flagged up as green. And they’re usually his biggest sellers. On this particular day, it’s turkey farfalle. It costs more than usual as the bird is local. But “if people want to do something [for the environment], they are willing to pay a bit more”, says Gloor.

In the long-term all 200 or so the Compass’ restaurants should be on board, says CEO Frank Keller. The company plans to “reduce goods that are bad in terms of CO2. That means that we have to think about our meat consumption. We can imagine having a ‘meat-free Monday’.”

The croissant

Manuel Klarmann, Eaternity’s earnest CEO, has plenty of statistics up his sleeve to make his case about how effective such a programme can be. The most important, and the one that started his company off, was the estimate that 30% of all greenhouse gas emissions are food related.

It was Klarmann’s partner, Judith Ellens, who had the original eureka moment that there should be a clear connection between the emissions in agriculture and what ends up on our plates. The start-up waded through hundreds of research and food databases to come up with their climate data, which they used to build a calculator for chefs. Compass was their first big client and the first all-important monthly reports of the worst and best CO2 meals served have now been sent out to restaurants.

For the Technopark, the worst offenders were the 160 kg of frozen croissants (equal to one tonne of CO2), served with morning coffees or in meeting rooms. The culprit: the high amount of butter they contain from the milk of methane-emitting cows.

“We have to look at how consumption patterns have changed in the last 50 years,” says Ellens. “What our grandparents ate was much more sustainable than what we have now. Now we can have milk and meat products any time of the year and as much as we like.”

Along with cutting down on dairy and red meat, Eaternity’s goals are for people to eat more seasonal and local food, and to avoid food grown in greenhouses. They’ll be happy when people start eating three climate-friendly meals a week.

“Food is one third of the greenhouse gases we emit,” says Klarmann. “We can see here in this [Technopark] restaurant how quickly we can reduce those emissions. You can’t just have the problem that you have way too much emissions in the food sector, but you also need to have the solution. And that would be the first time that we have it.”

Filling a gap

Young companies like theirs play a special role, adds Ellens. “As a start-up you really need to try and create your own niche in the market and you need to have something the others don’t have yet.”

VeganautExternal link is one Swiss start-up that sees an untapped area in trying to make vegan options more accessible. Its online platform allows users to upload data to maps to point people to the nearest vegan shop or restaurant.

“The technology available today is just great for doing these things and for showing that others are working on the same problem.” Sebastian Leugger started the company with his brother after a spell at the Impact start-up hub, paid for by WWF for his prizewinning plan for replacing dairy with plant-based foods. An animal rights activist and philosophy PhD, he helped launch political initiatives to promote vegetarian options in public canteens.

“I think it’s important for any movement to have people who try out new things and who don’t just talk about them. In the case of veganism it’s important to actually produce alternatives. Not just attitudes have to change, but the production of our food has to change, down to the level of agriculture.”

Cheese is Switzerland’s most important agricultural export. Each day the average Swiss drinks 2 dl of milk, and eats 60g of cheese and two yoghurts. Which puts Switzerland among the top dairy consumers in the world.

Leugger doesn’t see taking on the dairy industry in Switzerland as radical. “It sounds like it’d be completely useless to try and do something in Switzerland, but if you think about what the milk industry does to the cows and to the environment then it’s not so radical at all. Cows, even if they are not fed soy and corn, which they are, in Switzerland too, produce a huge amount of methane, because that’s just what cows do. If we want a good future in this country, we should produce less of these things.”

Changing the farmer

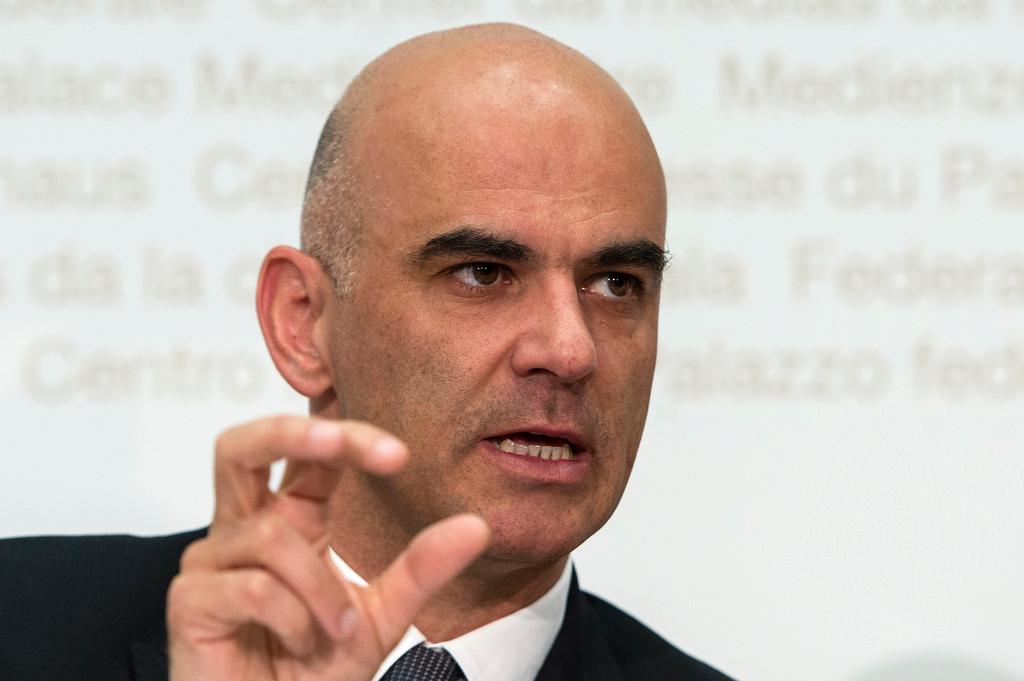

Switzerland’s head of agriculture doesn’t entirely disagree. A former farmer, Bernard Lehmann, says in recent decades the status quo was to produce more milk and more meat, with “no idea of what was happening to the environment”. Today his officeExternal link is looking to reduce that impact.

More

Your next meal could save the planet

“Methane is a violent greenhouse gas,” he states simply. “At the end of the day I think that the Swiss customer, the European and North American customer has to eat less meat.”

He acknowledges this isn’t something the farming community will find easy, but they “will have to adapt. We will eat more of the other things. The meat industry may reduce their business a bit” but they can help create jobs elsewhere in other industries like vegetable farming.

Being too “prudent” for economic reasons will prevent change in a positive new direction, he notes.

When it comes to dairy, Switzerland is pushing for dairy farmers to use grassland for feed, as opposed to cropland which it feels can be better optimised when used directly for human needs. It introduced a policy last yearExternal link to make this more attractive for farmers. “Drink a bit of milk, but milk with a lower impact on the environment,” Lehmann explains.

The need to innovate

But the office sees another major climate offender to be food waste. Up to 30% of the food we buy isn’t used. Some is recycled for biomass or compost. The rest is burned.

Outside the government’s role, which includes promoting sustainable agriculture by raising awareness of the scarcity of resources among the public and farmers, there is a need for start-ups, Lehmann says. And there are now many in this field.

“Young people today are more aware of the environmental problems of today and tomorrow, and more aware of the scarcity of resources. We have a big movement because young students think differently to how I do at 60.”

Start-ups can change customer habits and innovate in food processing, he says.

One new company doing just that is Zum Guten HeinrichExternal link, which takes surplus local fruit and vegetables from farms and repackages it into meals for Zurich office workers, transported around the city on a cargo bike.

Both the public and farming standards are to blame for food waste. Almost half of the food thrown away in Switzerland comes from people’s fridges. The other from food that is the wrong size or weight.

“Food waste produces a lot of CO2 emissions because a lot of energy is put into the production process of food and its transportation and storage. At the same time lots of water and land is used to produce these goods,” says Remo Bebié, one of the four climate, economic and food specialists running the start-up from the buzzing Impact Hub under the city’s railway tracks.

What started as a university project among friends has since become a full-time commitment – without pay. Now the company is finding it can’t cope with all the food farmers want to throw at them.

“Sometimes people will call and say I have 200 kg of pumpkins that I have no idea what to do with,” says Bebié. “Or what has happened before is a farmer will say, ‘hey, I have this whole area of my land where pears are hanging and I don’t have the time to pick them, do you want them?’”

They pay for the food to transfer a message that this food is valuable but are now partnering with a restaurant to help process the food. They have also run a crowdfundingExternal link campaign to buy a new bike. “It’s gone way beyond a student project and is something we really want to establish and see here in five years.”

“As a start-up you’re very flexible, you’re able to try new things, without running the risk of losing an established reputation. I think it would be difficult for established chains to do something like this.”

“In this specific problem I don’t think there is too much the government can do. The change has to come from the people. You can’t fix this in a top-down approach.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.