German speakers re-learn their language

What does it take for a mother-tongue German speaker to re-programme a language they have spoken their entire life? Some Germans who move to Switzerland are learning the dialect spoken in much of the country, in an effort to really fit in.

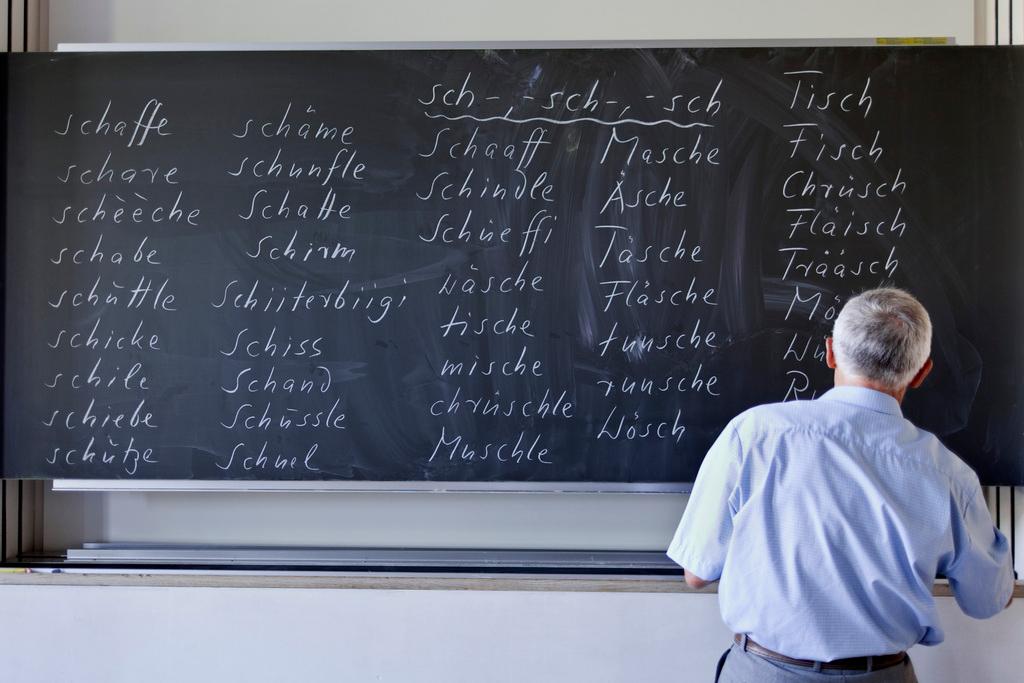

“Chhhhhhlapf…..chhhhhlapf.” Frank Roth is sounding out one of Swiss German’s less elegant sounds. The throaty rolling of the ‘ch’ is a key feature of the dialect – but it doesn’t come naturally to a mother-tongue German speaker, like those sitting around the table in a small classroom in Zurich one Tuesday evening. Roth is one of them.

“I was always a little bit angry about people who never learned German while working here, in international companies, and then I thought, I shouldn’t be angry at them as I didn’t even make the effort to learn Swiss German,” Roth told swissinfo.ch. “I decided – let’s at least try to learn it.”

Although Swiss German is the language spoken every day by most Swiss, high German is used for written communication. German is one of four national languages in Switzerland, alongside French, Italian and Romansh. German-speakers make up about 64% of the population.

Roth is originally from Swabia, a part of southern Germany, where the language spoken has similarities with Swiss German. He moved to Switzerland ten years ago.

“It’s been as [difficult as] I would have expected. If I speak my own dialect people do understand me, but it’s not Swiss German, and a few words are different. I really wanted to learn Swiss German the proper way.”

The class teacher, Michael Meierhofer, teaches two different groups at the Migros Klubschule training centre in Zurich.

“One is made up of German-speakers from Germany, and one is people who have learnt German as a foreign language, at least to an intermediate level,” he said. People’s aims are different, depending on their motivation to take the class.

Raquel Fandos learnt German as a foreign language, but speaks almost at a native level. “I was always hoping I would spontaneously start to understand Swiss German – but it never happened.” She has different goals from Roth. “My objective is not really to speak it, I would just be happy if I understood it, and didn’t have to say in every meeting at work, ‘please speak high German or I can’t understand you’.”

Getting the words out

Talking is a high priority in the class. Meierhofer encourages the students to write their own texts in Swiss German and to read them aloud to the group. They also listen and repeat phrases, as the way in which words are pronounced and the sounds of words are an important part of what sets high German apart from Swiss German.

“I try to create opportunities for speaking. Sometimes that goes better than others,” Meierhofer told swissinfo.ch. “It doesn’t just happen like magic. But Swiss German is already being spoken more often than high German [in class], and I’m very happy with that.”

Figures from Migros Klubschule show that the Swiss German-learners are in the minority however. More than 46,000 people started a high German course with the school in 2014, whereas only just over 1,200 took up a Swiss German class.

Meierhofer thinks there aren’t more people learning Swiss German because it’s “not expected”, as it does not have the status of an official national language.

“In some industries such as call centres or personal care, it is, but to work in Switzerland you need English as a minimum and German at the most,” he said. “Nobody expects a speaker of a foreign language to learn Swiss German, because it’s very difficult to master talking Swiss German without an accent.”

In Swiss German, the word “Chlapf” can mean car. In the following clip the class try to sound out some unrelated, but similar-sounding phrases.

More

‘Chlapf’

Apart from the accent, another issue with learning a dialect is that there are so many different variations in such a small country. From city to city, or even between valleys, there are vastly differing words and pronunciations.

The Swiss government does not have official figures on the number of dialects or the number of people who speak a dialect in Switzerland. The Swiss German DialectometryExternal link however is an online resource using data from the ‘Linguistic Atlas of German-Speaking Switzerland’, compiled in a web format by Yves Scherrer from the University of Geneva, and added to by Sandra Kellerhals of the University of Zurich. It combines data on dialects with google maps to show the many different variations around the country.

http://www.dialektkarten.ch/dmviewer/cluster.en.htmlExternal link

Scherrer agrees that to pin a number on how many dialects there are in Switzerland is difficult. “Dialects change gradually when moving from one point to another, and there are very few clear dialect borders where people could tell unambiguously from which side of a border a speaker comes from,” he told swissinfo.ch. “As a rough approximation, one could say that cantonal borders as well as the alpine main ridge still act as dialect borders in many cases.”

The identity link

Trying to get their heads around the intricacies of the Swiss German language is not only a linguistic challenge, it also brings up complex issues of identity – how does the language they’re learning sit with high German, when they have so much in common, but key differences? What message does it send to the Swiss when someone who already speaks German, adds another layer to their language – that of dialect?

Roth experienced mostly positive feedback from his Swiss colleagues. “There was not an expectation to learn Swiss German, but people appreciate it. I could feel that people talked to me a bit differently.”

His family didn’t react in such a positive way however. His parents said that when he talks he has a “Swiss German accent”. They correct him on dialect words that have crept into his vocabulary, and ask him “’why do you have to learn Swiss German? You will totally forget your roots and your accent’”. For Kurt’s parents, his learning of dialect was almost a betrayal of who he really is.

There’s no escaping it – dialect is personal. The choices made with language reveal a great deal about who we are, where we come from and who we want to be. For the Swiss German students, their attempt to master a dialect shows how personally invested they are in Switzerland. Meierhofer’s students have reasons beyond those of most high German learners – he believes learning a dialect is about much more than getting a job, for example. “Nobody learns Swiss German without some other personal motivation of their own. Those who do learn Swiss German are normally people who identify more with Switzerland – with the culture and with their general surroundings.”

Contact the author of this article on twitter @jofahyExternal link or on FacebookExternal link.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.